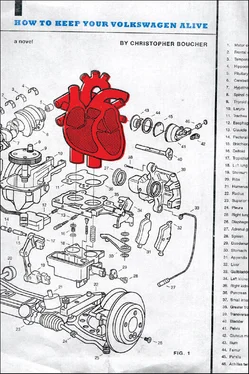

Christopher Boucher

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive

This book is for my father, who lives.

TUNE-UP

That afternoon we held a birthday party for my son, the 1971 Volkswagen Beetle. He was turning two, a quite young tide in Volkswagen years, so we set up some tables at Pulaski Park in Northampton, invited his friends from school — second graders, most of them — and ordered food from Nini’s (detective stories for the Beetle, pizza for everyone else). And a number of people brought cake — there must have been six or seven different kinds of cake to choose from.

The pizza/stories took longer to arrive than we expected, though, so the kids started playing a game — Red Rover, I think it was — with pieces of cake as the reward. And the VW kept winning, because of his size. At one point I looked up from a conversation I was having with another parent and I saw my son pointing his finger in his friend Ted’s face and singing the Queen song “We Are the Champions.” Then the Volkswagen ran over to the picnic table and shoveled half a cake into his mouth.

“VW!” I shouted.

His face became an operating table. “Wha!” he said, his mouth full. There was icing all over his face.

“How many pieces of cake have you had?”

He said something muffled.

“What?” I said. “Finish chewing first.”

He chewed and swallowed, and then said, “It’s my birthday!”

“Still,” I said. “Take it easy. There are detective stories on the way.”

The VW made a face. Then he said, “I can’t help it if I keep winning!”

“Remember that you’re bigger,” I said.

“So what? I’m still the freakin’ champion,” he said.

Finally, the pizza and stories arrived and the kids stopped playing so they could eat. The VW wasn’t supposed to have pizza, but I could tell that it was making him feel bad not to be able to eat with his friends. It was his birthday, after all, so I let him have a few pieces.

After the meal, we cleared the picnic tables away and one of the parents hung an evening-shaped piñata from a tree. All of the kids took turns swinging at it, but none of them could break it. When it came time for the VW’s turn, he put on the blindfold and his friends spun him around. Then they handed him the stick and he started swinging while everyone shouted directions: “To the left!” “No, higher!”

After a minute or so, though, the VW abruptly dropped the stick, took off the blindfold, ran over to a patch of tangy, sparkling green grass by the Academy of Music and vomited.

I ran over to help him. The vomit consisted of cake and pizza, of course, but there was also oil in it, and thus, the images of suffering.

I put my hand on the VW’s back. “I told you to go easy on that cake, didn’t I?”

The VW nodded.

“I don’t think your system’s set up to digest pizza,” I suggested.

Everyone was staring, and the VW looked desperate and embarrassed. He’d gotten sick like this before — at recess in school, at home, on the road — but never in front of so many people.

“You OK?”

He nodded yes, then doubled over and puked again.

The grass was now complete with images of suffering — black, shiny memories and promises — and I couldn’t help but study them. Members of our family were there, of course — the Soldier, the VW’s cousin Andy — but others, too, including me, the Lady from the Land of the Beans and a number of people I didn’t recognize. Some of the suffering was written, some imaged out.

We looked into the oil together. “Are those yours?” I said.

The VW coughed, spit, shook his head no. “Are they yours ?”

Behind us, the parents and children turned and went back to the party. I wiped the VW’s mouth and led him over to a picnic table. One of the other parents put the blindfold on his daughter and she started swinging at the evening. Soon the VW stood up and joined his friends. The girl swinging the stick began to connect with the evening—“thok!” “thwack!”—again and again.

Finally, she broke the piñata and small moments of time burst from the evening and poured into the dirt. All of the kids went wild, scrounging for minutes and stuffing them into their pockets.

The VW must have still felt ill, though, because he didn’t join the other kids in picking up the time — he stayed standing, looking down at his friends and trying to smile.

For the first time, he looked old to me.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

CONDITION

Someone — your mother, your daughter, your friend — is a Volkswagen, and that Volkswagen needs care or love or repair. You want to know how to help them, how they work, what makes them run, what you can do to keep them happy and healthy and moving forward.

I can help. I raised a Volkswagen, carried him from a newborn to full force, drove him all over western Massachusetts, broke down with him in every way, on almost every page. I fought news and nature, told the VW secrets and then cleared those same secrets from his filters, retrofitted him for sea travel and warfare.

It’s over now, the Volkswagen still and dark after almost three full years, these last instructions overheating and rolling to a stop by the side of the road. But he still lives in a way as well, as he runs by the reading. Plus, his Memory moves through these towns — you can catch him at Jake’s, having breakfast with his buddies, or parked out behind the Castaway Lounge in Whately, or zuckering along Route 47.

He was my son.

PRELIMINARY LIST OF TOOLS

One book about Volkswagens (a buildings-roman-itself; a coming-of-age-and-highwaying; an okay, if you say so, yes)

At least two good hands

One driving forward

A missing you can’t meet

One reading heart

Twelve gallons of liquid Haymarket-invention chai (No substitutions. You can taste it yourself — there is no replacement for the Haymarket!)

One basement kitchen, set for cold and dark and buggy

As many Volkswagen Beetles as you can find

THE STORY

Begin reading the first page and you’ll see, first and foremost, a story. There are no hidden implications here — it’s not that this book is made only of stories, nor are stories necessarily the most important components, but you can’t completely understand your Volkswagen without them.

My son’s story begins with pizza and a piñata but what it’s really about is the theft of my father, a slippery pasture I couldn’t track, and the hilltrills we traveled (which still live in my memory, even now, chords to verse). Anyway, I can tell it to you — the whole novel — in one story, a story I’ll call “Katydids at Noon.” We die and we are reborn.

One Sunday morning in the summer of 2003, my father was attacked by a Heart Attack Tree while sitting at our corner table at Atkin’s Farm in Amherst, Massachusetts (at least, that’s where the farm had been parked for as long as anyone could remember). I was twenty-seven at the time, chinning as a reporter and helping my Dad run the old Victorian apartment house that he owned in Northampton. I’d trained as a booker a few years earlier, but that’s not a road we need to go down; suffice to say that I’d tried it, frightened myself and given up. For years before that, my father and I had met every Sunday at Atkin’s for our Sunday morning griping session, or, as my Dad used to call it, our “Sunday Clipboard Meeting”—the one time of the week where we could sit back over coffee and breakfast and talk about things we couldn’t say to anyone else — bullshit, make plans, connect the present with the past. We’d bring lists of topics to cover; I stored mine in my power, and my Dad wrote his down on old envelopes and scraps of paper on a clipboard that he found at the town dump.

Читать дальше