THE TIMING BELT

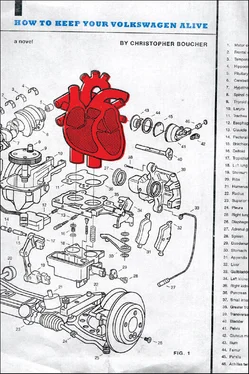

Keep in mind that every copy of How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive works differently (and some not at all!), that every book has its own unique personality or point of view — a point of view that you decide on or shape. Thus, some versions of this book speak to the makeup of your particular car while others have nothing to do with it. *

Remember, too, that you’re not alone in the Volkswagen — that there are people next to you in the back seat, and that you need to be kind to them. The fact that you might not recognize them doesn’t mean anything; for all you know they might be your mother twenty years younger, or your future grandson, or an image of the clock in the first classroom you ever kissed. We are all connected — each copy of How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive is wired together using special Volkswagen technology, thereby making the experience one of true, measured sharing. One of the chief concerns of this project is the possibility that might exist for this new type of collective reading, and what happens to a story, say, when two hundred pairs of eyes are looking at it at the same time. Some words can stand that gaze, I’m sure, but others will spring leaks, will crack, will weep. In every case, the story itself will be changed.

We will see what happens! We won’t know, though, until the book is in everyone’s hands and everyone turns to the first page.

So go ahead. Do it — open the book. See? You see me, right? And I see you . See? I am reading your face, your eyes, your lips. I know the sufferdust on your brow. I can see you reading and I can tell, too, when you are here, when you’re absent, what you’ve read and how it affects you. There is no more hiding. I see your chords — your fractures, your cold gifts, where and when you’ve hurt people and why. It’s all right there — your stories are written right there on your face!

• • •

Sigh. All I have is now in your hands — the pieces and parts of manual and story, a collage of loss, that make up the VW Beetle. And even though he’s just a vehicle(a guffarian, a here-to-there), I always trusted him to carry us forward. The VW believed (even when I didn’t) that we were saving something — that just by reading and writing, shifting and steering, we were helping to keep something alive . And he was right — we were.

Oop — look at the money. It’s time to go.

Here — take this key. It’s called “How to Use This Book.” It starts the car, gets us going. Together, we will move forward through these were-cities and yester-hills and towards a deeper understanding of the art of loving and sustaining (at least for a time) the machine of parts and memories that is your Volkswagen Beetle.

INTRODUCTION

I wish I could take you to the China House on the Smith College campus.

I never knew much about the China House, except that it was a little covering about the size of a shed with a bench inside. You could sit on the bench and look out at Paradise Pond. The hut was old, and built off of an actual tree — the limbs ran right through the wood.

The first time I took the VW to the China House he thought it was his mother. “I swear to god that I was born here,” he told me as we sat on the bench. “I have distant memories of seeing this first.”

“Those Memories aren’t real — it just means that I need to clean the filter,” I said. “You know very well that you were born in our home on Crescent Street.”

“That’s your Volkswagen,” he said. “Mine is, I was born in these knotty arms.”

I was annoyed at his fibs. “VW—”

“This pond was the first thing I ever laid eyes on,” he said.

At one point or another I’ve taken everyone I ever cared about to the China House: my father, my brother, the Memory of My Father, the Two Sides of My Mother. I took most of my girlfriends there as well — the Lady from the Land of the Beans, the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass, the Scientist.

The China House is supposed to be a place where you reflect back and meditate, but I tried meditating several times without result. My understanding was, you were supposed to be very still and something would come to you. But nothing like that ever happened to me. I closed my eyes and all I saw were flashes — a diner, its walls molting; a greenhouse blowing its nose into a hankie and straightening its tie.

Maybe the China House was his mother, the cut wood and the live tree cousins! Did I have faith and then forget?

Those trystips were years ago, though — one day in the fall of 2005, the China House submitted her resignation to the pond and moved away. I heard two conflicting stories explaining why: First, my friend the Chest of Drawers told me that she fell in love with a comedian and moved with him to Fall River, Massachusetts. Later, though, I heard that she was admitted to law school.

The Chest warned me about the China House’s departure a few weeks in advance, though, and when he told me I made a mental note, a score on my memory coil, to go sit with the House one more time before she left. But it was a busy time — I was working as a wire in order to keep my car on the road — and the idea slid down my spine and somewhere into my body where I didn’t even think to look for it.

It wasn’t until that winter, when the snow came, that the China House’s absence became my absence. One morning a few months after the Volkswagen’s death, Northampton woke up to a literary snow squall — eighteen inches of flakes of torn paper falling from the sky. The paper, as it settled, was so heavy that the plows couldn’t move it. No one could work or drive or think clearly — everyone stayed home in their kitchens.

But I was living as an angle-fish on Elm with a roommate I couldn’t stand — he read me his original librettos whenever I came out into the common rooms — so I bundled up and went out for a walk. Nursing a grapefruit of sadness in my belly, I made my way over to the Smith College campus. I was looking for the peace that only the China House could offer me. But when I walked down the hill towards the spot where the House had been, I remembered that she was gone — that she’d moved away to start a new life.

As I walked down the footpath, though, I peered through the falling paper and saw a new house standing in the China House’s place. This house wasn’t shed-like and quiet; it was red, with vinyl siding, and when I stepped closer it said, “Welcome to the Meditation Station!”

I was cold, so I stepped inside. It locked its doors.

“Want peace?” the voice asked. “Want the moment ? Well you’ve come to the right place. Please wait,” the voice said, and I could feel it scanning me, sending signals through my legs to test the blood in my veins. I could hear it computing. Then it said, “Your peace level is a—” it paused, “three. Want more?” Then it named its price.

At that moment I really missed the old China House. Though I knew it wouldn’t — couldn’t — hear me, I told this new house that I just wanted to sit here quietly and listen to each piece of page, shuffling down from the sky, falling on the pile of brother-, mother-, and sister-pages and settling to rest.

KATYDIDS AT NOON

The Invisible Pickup Truck didn’t see the Tree’s attack on my father, but he did hear it — he told me later that he was parked at the far end of the lot, and reading a novel about trout, when he heard the sound of a window shattering. He said he also remembered the noise my father made — an unk , he said — as the Tree split open his chest. Atkin’s, caught off guard, began to rev and vibrate nervously, and employees came running from behind the deli counter. The Truck came running, too, and when he saw my father’s body dangling from the Tree he tried to tackle him, slamming his face right into the Tree’s knee.

Читать дальше