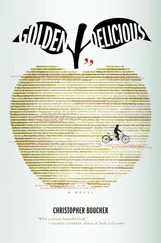

When we came home that night we got a fresh glimpse of the Fear of Death, still tacky in the half-light. The color made the house look tragic, like carry-on luggage. House = luggage, flight = cavity/chest.

Plus, that evening the neighbors started calling about the color, and a few even knocked on our door. One man, a neighbor we’d never met before, had hair of solid gold. He stood in the doorway and said, “Tell me that’s a primer.”

I’d thought the Memory of My Father would have sworn at him, but by this point he was my father a few years later, and he was calmer and more content. “No,” he said. “That’s actually the color.”

“What color is it?”

“It’s called Fear of Death.”

The neighbor crossed his arms, sighed and looked again at the front of the house. “Boy,” he said. “I mean, it completely changes the neighborhood.”

The Memory of My Father didn’t say anything.

The man looked at him and said, “You’re staring at my hair.”

“No — no,” the Memory of My Father said.

“You are.”

My father even older now, the Memory of My Father flickered shyly and held up his hand. “Sorry, hey. I mean,” he said.

“It’s extremely heavy, in case you wondered,” the man said.

“I can imagine.”

“I constantly look for places where I can rest it.”

“Well here,” the Memory of My Father said. He held out his hands and the man put his gold head in them.

As the light faced the firing squad the Memory of My Father and I sat outside on the back patio, sipping the Memory of Beer. The Memory of My Father winced and custom-swore when he cracked the can, just like my father used to.

We both took deep sips as we looked at the color in the dark. Even lightless you could see its images.

After a moment the Memory of My Father asked, “Is it that bad?”

I reached into the swamp of my heart. “Course not,” I said. “It’s true . Who cares if it has meaning and weight?”

“I didn’t mean to offend anyone with it,” said the Memory of My Father, now my father as an old man — just weeks before the attack. “I just picked up the brush. It did all the talking.”

“I know the name of that tune,” I told him, and we both took a slug.

We sat there for a while more. Then the Memory of My Father fell asleep in the metal chair, and the chair wrapped its arms around him and held him there. I watched them lie together for a few minutes and then I put down my beer, stood up, went over to the side of the house and put my hands to the paint.

It was still alive — not yet dry, not yet dead. I touched it and it touched me back. All at once I knew Memories I’d forgotten, images that had made me. I felt an incubator. I knew the warm breath of my first refrigerator, the smell of the yellow kitchen floor. The first sign of an old soldier I never knew, his beard a forest of dying snow.

JAWS

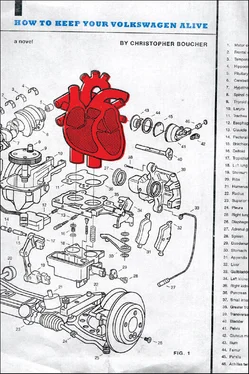

If the quiet, teethy taupe of your VW’s dashboard legumes, the VW is asking for Jaws—the Jaws Junkyard, on Route 66 in Westhampton. There are several junkyards in western Massachusetts — Highway Auto, Ludlow Salvage — but I know of no other yard as volkstocked as Jaws. They literally have rows of VW corpses to pick through. Also, they have a car in the front yard that was once a shark. I’m serious; it has fins and teeth but it drives on the road. I’ve never seen anything else quite like it.

I think of Jaws now and my lungs ache. How many afternoons, pre-attack, did I spend there with my father, picking through bodies for parts for our cars?

What I’m saying is, they have great prices.

If you do go to Jaws, though, remember that not all Volkswagens are the same. Some have external feeders, others have internal ones and some burn paperless altogether. I once lifted up an engine compartment lid on a VW at Jaws and found a nest of screaming birds. I opened another and found a field of crops. Where were the morning cables — the combustion chambers? I have no idea how it could be that the inside of each was so different, but there it was, for our review, the VW undercover variation.

Even so, always be sure that the part they give you is right for your car — the balloons at Jaws’ll sell you any old part they can.

One time, the VW and I went out to Jaws to see about getting a new believer—the circuit which connects the storypump via sunrise to the middle transmission. In the weeks before that, the VW had stopped believing in almost everything — the road, the book of power, every story I told him. That’s how I knew his believer was shot.

So I did what I had done so many times before — I drove us out to Westhampton, parked the VW at the salvage yard entrance and stepped into the office trailer. I spoke to a dirty red balloon who was sitting behind the counter, reading a magazine and eating a grinder. *When I leaned against the desk I could hear the stories in his chest — one about volume, another about a new set of curtains. He looked up at me and I said, “Looking for a new believer for my son.”

The balloon put down his food and swiped his hands together. Then he picked up a clipboard. “What year is your son’s car?”

“He is the car.”

“What year?”

“Seventy-one,” I said. “Beetle.”

The balloon flipped a page on the clipboard. “Only one we have is a four-point from a state prison.”

“A prison ,” I said.

The balloon nodded. “It should work. Beliefs for Bugs and state prisons—” he scanned the page—“should be interchangeable.”

“You sure?”

“That’s what the listing says.”

“You don’t have any VW believers — factory parts?”

The balloon let out a little air. “This is the only believer that I have on the whole lot,” he said.

“How much?”

“Three and a half,” he said.

“Could you order a Volkswagen-type believer from another yard?”

“I can put your name on a list,” he said. “You need it right now?”

I looked out the window of the trailer and saw the VW studying a puddle of mud and antifreeze.

“I really do,” I confessed. “Poor kid doesn’t know what to believe.”

• • •

From the moment the balloon handed me that dead, grey part (which, incidentally, was about the size and shape of a bagel), though, I should have known that it wasn’t going to fit. But like a reese I bought it, took it home and tried to install it. When I removed the old believer, I found that it had five points — not four, like the prisoner. Nevertheless, I installed the new one and hoped for the best.

I knew immediately that it was a mistake. Shortly after the transaction, the VW asked me what time “chow” would be served. Later that night, he asked me about getting a tattoo.

For two days, the VW believed he was a prison. Every other word was caged — he spoke about solitary confinements and inmate rehabilitation. One night at dinner the following week, I asked him what his plans were for the evening and he mentioned his hopes to review proposals for new community outreach programs.

That was it — I’d heard enough. I threw down my fork and knife. “In the morning I’m taking you back to Jaws,” I said, “and we’re going to get you a new believer.”

“If we can put these inmates to work, Dad—”

“Enough,” I said.

“—we can help them and help the community.”

I went back to Jaws the next day and spoke to the same balloon. “It doesn’t fit,” I said. “The kid believes that he’s a state prison.” I handed him the old, rotten believer. “See how this one has five points? The one you gave me has four.”

Читать дальше