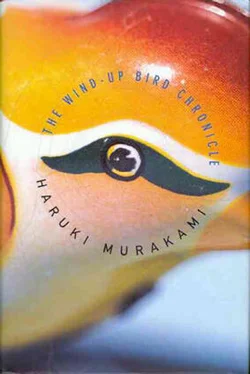

Somewhere around waist height in the darkness, I could see a whitish glow with a square shape. It was the glow of the computer screen, and the bell sound was the machines repeated beeping (a new kind of beep, which I had not heard before). The computer was calling out to me. As if drawn toward it, I sat down in front of the glow and read the message on the screen: You have now gained access to the program The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Choose a document (1-16).

Someone had turned the computer on and accessed documents titled The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. There should have been no one in the Residence besides me. Could someone have started it from outside the house? If so, it could only have been Cinnamon. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle?

The light, cheery sound, like sleigh bells, continued to emanate from the computer, as if this were Christmas morning. It seemed to be urging me to make a choice. After some hesitation, I picked #8 for no particular reason. The ringing immediately stopped, and a document opened on the screen like a horizontal scroll painting being spread out before me.

26The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle #8 (or, A Second Clumsy Massacre)

The veterinarian woke before 6:00 a.m. After washing his face in cold water, he made himself breakfast. Daybreak came at an early hour in summer, and most of the animals in the zoo were already awake. The open window let in their cries and the breeze that carried their smells, which told him the weather without his having to look outside. This was part of his routine. He would first listen, then inhale the morning air, and so ready himself for each new day.

Today, however, should have been different from the day before. It had to be different. So many voices and smells had been lost! The tigers, the leopards, the wolves, the bears: all had been liquidated- eliminated-by soldiers the previous afternoon. Now, after a night of sleep, those events seemed like part of a sluggish nightmare he had had long ago. But he knew they had actually happened. His ears still felt a dull ache from the roar of the soldiers rifles. That could not be a dream. It was August now, the year was 1945, and he was here in the city of Hsinching, where the Soviet troops that had burst across the border were pressing closer every hour. This was reality- as real as the sink and toothbrush he saw in front of him.

The sound of the elephants trumpeting gave him some sense of relief. Ah, yes- the elephants had survived. Fortunately, the young lieutenant in charge of the platoon had had enough normal human sensitivity to remove the elephants from the list, thought the veterinarian as he washed his face. Since coming to Manchuria, he had met any number of stiff-necked, fanatical young officers from his homeland, and the experience always left him shaken. Most of them were farmers sons who had spent their youthful years in the depressed thirties, steeped in the tragedies of poverty, while a megalomaniac nationalism was hammered into their skulls. They would follow without a second thought the orders of a superior, no matter how outlandish. Commanded in the name of the emperor to dig a hole through the earth to Brazil, they would grab a shovel and set to work. Some people called this purity, but the veterinarian had other words for it. An urban doctors son, educated in the relatively liberal atmosphere of the twenties, the veterinarian could never understand those young officers. Shooting a couple of elephants with small arms should have been far easier than digging through the earth to Brazil, but the lieutenant in charge of the firing squad, though he spoke with a slight country accent, seemed to be a more normal human being than the other young officers the veterinarian had met-better educated and more reasonable. The veterinarian could sense this from the way the young man spoke and handled himself.

In any case, the elephants had not been killed, and the veterinarian told himself he should probably be grateful. The soldiers, too, must have been glad to be spared the task. The Chinese workers may have regretted the omission-they had missed out on a lot of meat and ivory.

The veterinarian boiled water in a kettle, soaked his beard in a hot towel, and shaved. Then he ate breakfast alone: tea, toast and butter. The food rations in Manchuria were far from sufficient, but compared with those elsewhere, they were still fairly generous. This was good news both for him and for the animals. The animals showed resentment at their reduced allotments of feed, but the situation here was far better than in Japanese homeland zoos, where foodstuffs had already bottomed out. No one could predict the future, but for now, at least, both animals and humans were being spared the pain of extreme hunger.

He wondered how his wife and daughter were doing. If all went according to plan, their train should have arrived in Pusan by now. There his cousin lived who worked for the railway company, and until the veterinarians wife and daughter were able to board the transport ship that would carry them to Japan, they would stay with the cousins family. The doctor missed seeing them when he woke up in the morning. He missed hearing their lively voices as they prepared breakfast. A hollow quiet ruled the house. This was no longer the home he loved, the place where he belonged. And yet, at the same time, he could not help feeling a certain strange joy at being left alone in this empty official residence; now he was able to sense the implacable power of fate in his very bones and flesh. Fate itself was the doctors own fatal disease. From his youngest days, he had had a weirdly lucid awareness that I, as an individual, am living under the control of some outside force. This may have been owing to the vivid blue mark on his right cheek. While still a child, he hated this mark, this imprint that only he, and no one else, had to bear upon his flesh. He wanted to die whenever the other children taunted him or strangers stared at him. If only he could have cut away that part of his body with a knife! But as he matured, he gradually came to a quiet acceptance of the mark on his face that would never go away. And this may have been a factor that helped form his attitude of resignation in all matters having to do with fate.

Most of the time, the power of fate played on like a quiet and monotonous ground bass, coloring only the edges of his life. Rarely was he reminded of its existence. But every once in a while, when the balance would shift (and what controlled the balance he never knew: he could discover no regularity in those shifts), the force would increase, plunging him into a state of near-paralytic resignation. At such times, he had no choice but to abandon everything and give himself up to the flow. He knew from experience that nothing he could do or think would ever change the situation. Fate would demand its portion, and until it received that portion, it would never go away. He believed this with his whole heart.

Not that he was a passive creature; indeed, he was more decisive than most, and he always saw his decisions through. In his profession, he was outstanding: a veterinarian of exceptional skill, a tireless educator. He may have lacked a certain creative spark, but in school he always had superior grades and was chosen to be the leader of the class. In the workplace, too, others acknowledged his superiority, and his juniors always looked up to him. He was certainly no fatalist, as most people use the word. And yet never once in his life had he experienced the unshakable certainty that he and he alone had arrived at a decision. He always had the sense that fate had forced him to decide things to suit its own convenience. On occasion, after the momentary satisfaction of having decided something of his own free will, he would see that things had been decided beforehand by an external power cleverly camouflaged as free will, mere bait thrown in his path to lure him into behaving as he was meant to. The only things that he had decided for himself with complete independence were the kind of trivial matters which, on closer inspection, revealed themselves to require no decision making at all. He felt like a titular head of state who did nothing more than impress the royal seal on documents at the behest of a regent who wielded all true power in the realm-like the emperor of this puppet empire of Manchukuo.

Читать дальше