He brings a hand over his jaw and stares at the plate. “For this particular delicacy?” he says. “I would probably suggest a Benoit-Levy Chardonnay.”

“Sounds perfect,” she says and he disappears again. She looks down at what he’s presented — a wheel of fat, beige spokes of oyster drizzled with a heavy-looking, rust-colored sauce.

She spears one of the oysters with the fork and puts it in her mouth. She tastes the garlic and the lemon and the Worcestershire, lets the oyster rest on her tongue and its juices run down and into the well of her mouth. It’s fantastic. She’s not even this big oyster fan, but this is tremendous, the kind of food that justifies words that normally seem pretentious or clichéd when you read them in magazines— succulent, savory, delectable. She can’t believe the Spy has never done a write-up on this place.

The waiter brings the wine in a flamboyant glass, shaped, of course, like a rose in full bloom. She takes a sip, lets it pool around her tongue for a while before swallowing. She’s immediately overwhelmed by taste, by shadings and gradations she didn’t think she had the capacity for, and she wants to laugh. She’s feeling giddy. She’s thinking, not really seriously, that the blow to the head has transformed her, thrown switches that have been shut down since childhood. It’s like some archtypal comic book story, the eternally boring and noble scientist caught in the lab explosion, knocked to the gleaming floor underneath the shards of her equipment, broken test tubes and splintered Pyrex beakers, green smoke rising up to the ceiling, the whole room bathed in an ultraviolet glow. And then she emerges from the rubble, larger than before, her muscles forcing the seams of her lab coat to burst, her eyes now bulging just a bit from the sockets. And a slightly mad smirk across her lips.

Sylvia closes her eyes and fixes her mouth around another oyster. She sucks on it, refuses to swallow right away, puts all her concentration into discovering flavor. And then she senses someone standing next to her and gets embarrassed, as if she’s been moaning over the food. She opens her eyes and swallows and says, “Absolutely wonderful.”

But it’s not the waiter. It’s the kid with the big ears who was reading the notebook when she came in. He just stands there, awkward and hesitant, smiling, nodding his head.

“Oh, God,” she says, “I thought you were the waiter,” then adds, “Is there something I can do for you?”

“I’m glad you like the food,” he says and she picks up an accent she can’t place. “Papa will be happy to hear.”

She’s annoyed. It’s not often you get the kind of enjoyment she was pulling out of this lunch and this kid has just stepped on it. It simply isn’t going to be her day. She stares at him and waits for his pitch.

“Marcel’s in the kitchen,” he says.

Sylvia looked at him like she doesn’t understand.

He flinches just a bit and says, “Marcel,” and jerks his thumb toward the kitchen door. “The waiter.”

“You must be a regular,” she says and then she could shoot herself for extending the conversation.

“It’s a quiet place to come,” he says. “A good place to work. Undisturbed.”

“That’s good to know,” she says, resigned to the interruption now. “I take it you’re a student?”

He shakes his head no, seemingly embarrassed, starts to fish around in every pocket of his suit. “I just wanted to give you … I seem to have left my cards … forgive me, I’m not very good at this. I’m a filmmaker.”

Sylvia’s stomach churns with the last word, but she steadies herself.

“I’m glad for you,” she says, picking up the wineglass. A beat goes by. The boy looks from her face to the kitchen, but he doesn’t seem to know what to say.

“Well it was nice meeting you,” Sylvia tries, but he ignores the words and bulls ahead.

“You like film?” he asks.

She doesn’t want to prolong the interruption but she can’t help asking. “What’s your name?”

“Jakob.”

“Jakob,” she says, “have you ever met anyone who didn’t like film?”

He doesn’t seem to understand the question and when he pulls out the opposite chair and sits down she realizes she’s made a big mistake.

“My father,” he says, challenging, “he hates the cinema. I doubt he’s ever been to a movie in his life.”

“He’s indifferent,” she says.

“Excuse me?”

“He’s indifferent. It’s not that he actively dislikes movies. Film just isn’t a big part of his life. He’s indifferent to it.”

“No,” he says. “This is not the case. Not in this instance. I have to disagree.”

She sighs and says, “Well, I guess you know your old man.”

Either the kid is genuinely lame or he’s playing the part to avoid leaving the table. He smiles and shakes his head as if she’s putting him on and they both instinctively know it.

“What about yourself?” he says. “Are you an enthusiast?”

She thinks about just ignoring him, but decides that’s actually more work than giving in and talking.

“I don’t get out as much as I used to,” she says. “But I used to go a lot when I was younger.”

“I knew it,” he says. “What are some of your favorites? Who would be your favorite director?”

“Fritz Lang,” she says, spearing an oyster and remembering Dr. Jessner from German Giants class in college.

It’s a mistake. Her answer sends Jakob into something approaching a spasm.

“Lang,” he says, voice too high. “Really, Lang. You’re a Lang devotee, yes? I knew it. I knew this. How many people even know Lang today? Unbelievable. I saw you walk in, I said, film woman, yes, I knew it.”

“Film woman?”

“Who else? Please. Who really does it to you?”

It’s strange. Having someone ask her opinion.

“Murnau,” she says, “Dupont—”

“A weakness for the Germans—”

“—Herk Harvey, Browning, Dovzhenko—”

“A buff,” he says. “You’re what they call a buff.”

“Oh, c’mon,” she laughs, protesting like some easy prom date. But suddenly she doesn’t mind him sitting at the table.

“I bet you don’t mind going to the films alone. Correct? Yes? They say a real buff never minds going alone.”

“That’s in the book,” she says. “That’s one of the definitions.”

“How about Schick?” he says. “Do you know any Schick?”

It stops her cold. She puts down her wineglass and stares at him.

“What is the matter?” he says, sticking his neck out.

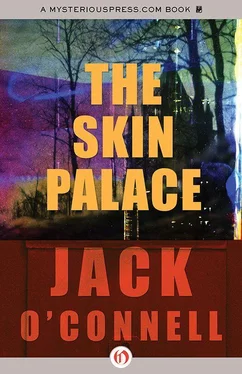

Sylvia doesn’t know what to say. She feels like she should be angry, but she’s mostly confused. Did Schick send this kid down here as some kind of joke? But Jakob was here before her. He was sitting in here reading when she came in the door. Schick couldn’t have known she’d be coming here because she didn’t know she was coming here. Maybe the kid saw her come out of Herzog’s. Maybe he saw her leave the Skin Palace and ran to get here first. But again, how could he have known she’d come in here?

She knows she should just get up now and leave. Put some money on the table and get the hell out. There’s no need for her to be here. She shouldn’t be drawn here in the Zone in the first place. What’s happened today just proves that.

She throws down the rest of the wine in one huge gulp and starts to push away from the table.

“What’s wrong?” Jakob says, sitting back.

“I’ve got to go,” she says and stands up.

He gets close to panicky. “Forgive me, please. What did I say?”

Sylvia nods goodbye and moves around the table, but Jakob stands up, mortified by some unfathomable social mistake, and starts to follow her to the door. She reaches for the doorknob and he puts a hand on her shoulder and says, “Hold on, please. What is the matter?”

Читать дальше