No one answers and she goes on, maybe a little conciliatory.

“I was just trying to warn you. Hugo’s been known to go into anyone’s wallet for financing. We’ve emptied out more than one trust fund to sustain his career.”

She says the last word like it was obscene.

A beam of light hits Sylvia in the eyes and then moves on to Leni and Hugo. They all squint to see one of the bouncers from outside.

“Turn that off,” Hugo hisses and the bouncer complies, slides into the aisle below and whispers to Hugo that things have calmed down out in the street.

Hugo nods and takes a deep breath.

“All right. Go tell June to get the lawyers and Counselor Frye on the phone. Set up a conference call. Then have Ricco get down to the Spy and find out exactly what happened. Have him tell Starkey I’m very disappointed.”

The bouncer trots off and Hugo turns his attention to Sylvia. He takes her right hand and holds it up in front of him.

“It looks like you can venture home now, my dear. The rabble has been dispersed.”

“Tremendous,” Leni says, sliding out of her row. “I’m late at the masseuse.” She stops in the aisle and says, “Always a pleasure meeting my public.”

They all nod agreement and watch her run down the balcony stairs.

“I guess I can go,” Sylvia says to Hugo, suddenly feeling awkward and frightened.

He squeezes her hand, gives a tight-lipped smile and a nod.

“Schick,” he says, releasing the hand and fishing in his coat pocket, “is a true believer in the strange ways of fate.”

He pulls out a business card and extends it toward her. She takes it and says, “I want to thank you again. If you hadn’t pulled me inside, I don’t know what—”

He cuts her off with a wave of his hand.

“We were meant to be brought together, Sylvia. The method is always inconsequential. I feel a genuine connection here. I feel a kindred outlook, a mutual way of seeing things.”

Sylvia laughs and brings a hand over her mouth. Someone from down below in the audience shouts, “Shut the hell up.”

Hugo shakes his head and whispers, “We must walk amongst the ignorant. That is one of the costs of our art, yes?”

She shrugs and says, “Honestly, thanks again. You saved me.”

He smiles a long minute, then says, “I’m throwing a party, Sylvia. Really, a working party. After seven years of toil, we are filming the finale of my great albatross— Don Juan Triumphant. I would love for you to attend. We are filming this Wednesday night. I think you’d find it fascinating. You’d get a chance to see the final flourishes in the creation of a masterpiece. And you could bring a camera.”

He’s caught her off guard. She stammers, “Oh, I don’t—”

“Wednesday night,” he says. “Give it some thought. As they say, sleep on it.”

She simply nods and whispers, “Thanks again.”

She makes her way out of the seats into the aisle and follows Leni’s course out of the balcony without waiting for Hugo. When she gets to the corridor she looks back and when Schick doesn’t appear she guesses that he’s stayed to watch the rest of the movie.

She comes to the end of the corridor, to the huge stairway down into the lobby and as she’s about to turn the corner onto the stairs, something catches her eye. Just an instant, just a momentary flash of image. She stops and stares at a print that’s framed and mounted on the wall. She steps back to get her focus. It’s a black-and-white shot. Stark. A little frightening. A Madonna and Child shot. A decaying landscape hosting the mother and infant.

It’s a Terrence Propp.

Sylvia can remember, with an almost visceral, at times uncomfortable clarity, this late-fall afternoon, a Friday and a day just like today when she was walking home from Ste. Jeanne d’Arc and all the old men down Duffault Ave were out in the gutters with their ancient wooden rakes pushing leaves into piles and lighting them on fire, back when it was legal, and the wind was picking up and just engulfing her in the smell of leaf-smoke. And it was after three o’clock and there was about an hour of sunlight left to the day. The sky was already this same slate color, this exact ghostly feel to it, low clouds but a kind of brittle clarity to the air. And after Elsie Beckmann turned off at Jannings Hill, Sylvia was walking alone and she knows, she’s certain, she was daydreaming, completely into some imagined world, though she no longer had any remembrance of what it was. She does remember being brought back to Duffault Ave, though, by the awful weight of her schoolbooks and by the coating of sweat that had broken out under her uniform. She can remember thinking how strange it was, perspiring in the middle of this October wind.

By the time she made it up the driveway to her back door, all her strength was gone and she sat down on the back stoop and just put her head down on her knees. She has no idea how long she sat there before her mother lifted her and carried her up the rear stairway to the apartment and put her on the couch.

For the next forty-eight hours, Sylvia sweated out the worst flu and fever of her life to date. She mumbled and cried every time the cold washcloth on her forehead was changed. Sylvia has no recollection of those nightmares. She doesn’t even have much of a picture of her recovery beyond eating Campbell’s chicken noodle soup off a tray in bed, while watching some old forties movies on the little black and white TV that Ma propped up on the dresser. Sylvia was well again by Monday and back at school on Tuesday.

And now, for whatever reason, that Friday afternoon, walking home from school, after the first symptoms of fever came over her but before she collapsed on the back stairs, those moments comprise the most haunting memories of her childhood. She has no idea why, but the feeling of light-headedness, the smell of the leaves being burned, the unnatural clarity of the darkening sky, the warmth building up under her arms, the heaviness of her feet inside her shoes — all of these sensations continue to be as real and strong to her as the day they first happened.

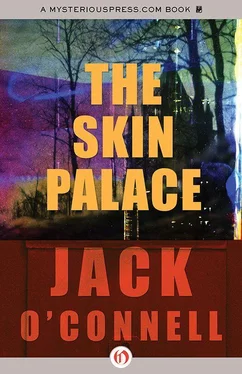

And it’s how she feels now, at this exact moment, walking down Verlin Avenue, as if locked in slow motion in comparison to the people passing by. She’s a block from the Skin Palace. When she came down to the lobby, another bouncer directed her down a long, dim corridor toward a red exit sign and she emerged out the rear of the building. When the sun and air hit her, she lurched into that same light-headed, slowed-down state as that Friday afternoon fifteen years ago.

It’s not exactly an unpleasant feeling, though there’s almost a latent fear that sickness will come. It’s more this otherworldy pocket, this dreamy, growing warmth that’s threatening to go out of control from the start. There’s a tightness to the joints, but at the same time an almost loose feeling to the skin, to the whole head. She knows that she needs to be hailing a taxi or calling Perry. But it’s as if her knowledge of this has little or no connection with her inability to make her body comply, as if the center of her intellect has shifted and is now located in her legs and feet. They’re pulling her along Verlin, keeping her in motion, though she doesn’t know where it is she’s heading. This isn’t the way out of the Canal Zone. It isn’t the way back to the apartment.

She walks another half-block. The feeling seems to begin to dissipate one second and reassert itself the next. She suddenly wonders if maybe she was hurt worse than she thought in the skirmish. Maybe she’s got a slight concussion. She forces herself to stop walking and leans up against a lightpost. She takes some deep breaths and closes her eyes. She stands completely still for a few minutes and starts to feel better, then puts her hand up to her cheeks and forehead and they feel normal to her. It’s probably just the shock of the past hour, she decides.

Читать дальше