She picks up her wineglass, stares into it. She swallows, tries to stay calm and says, “I didn’t mean to offend—”

“And I didn’t mean to be rude,” Gaston says, lowering his voice. “It’s just … this is such a crucial time for the Proppists. There’s so much infighting lately. And so many rumors. Finding the right direction, staying on the right path, keeping the eyes open and clear. The stress is increasing daily.”

Sylvia looks up at the ceiling and stares at an intricate mural of a Renaissance-style bedroom scene where a ghostly young virgin is preparing to surrender her maidenhood to what looks like a hulking incarnation of Pan.

She looks back down at Gaston and thinks, this guy has seen too many Sydney Greenstreet movies. “I think I’ve heard the call, but I’m ignorant. I have no idea where to go from here. I need some information and I was told you could give it to me.”

Gaston rocks his chair back on its rear legs as if the process will help him think. A smile comes over his face and he says, “You’re toying with me, aren’t you? Did Camille put you up to this?”

“I don’t know a Camille,” Sylvia says, “just like you don’t know a Quevedo. That makes us even. So why don’t we do each other a favor and stop trying to outmaneuver one another and just tell the truth.”

It’s a pushy move, but it’s all she has left.

“What if you don’t like the truth?” Gaston asks.

“I’m an adult,” Sylvia says. “I’ll survive.”

He nods, seems pleased, takes another hit of wine and says, “Okay, Sylvia. The truth is I have no idea who Terrence Propp is. None of the Proppists do. I have no idea what the man even looks like. I’d walk right by him if I passed him on the street.”

Now Sylvia’s on the verge of furious. “So this is all a huge joke,” she says. “I’ve wasted my entire day down here so someone could have fun at my expense. You—”

He cuts her off. “Calm down. Please. Believe me, we were once as anxious to know as you. We’ve all tried to follow the man’s trail. None of us has ever been successful. I can give you a kind of sketchy history. But eventually it dissolves into vapor. The one thing we can be completely certain of is that Mr. Propp takes his privacy extremely seriously. If we were forced to speculate on the causes for this I suspect we’d regress into endless debate. There are some known facts. At some point, though we can’t completely confirm the years, Terrence Propp certainly lived here in Quinsigamond. We’ve narrowed down his residence to three or four likely addresses. All of them walk-ups here in the Canal Zone. And though dozens of the local raconteurs claim to have known Propp, the only person we give credence to is Elmore Orsi over at the Rib Room diner.”

The Rib Room diner.

Where Sylvia found the ad for the Aquinas.

“And these days, Orsi’s started to recant,” Gaston says. “He now claims he’s never met Propp. That it was all a stunt. He thought it would help his restaurant business. In any event, here’s what we know for certain.”

He gets up and walks to the bar, reaches underneath and returns to the table with a small pamphlet or magazine which he rolls up and hands to Sylvia without any explanation.

“First,” he says, “there are currently forty-nine known Terrence Propp prints in existence. Second, most of the known prints were taken in or around Quinsigamond. And third, exposure to and study of these works leads the viewer to a deeper, fuller understanding of their own sensual potential.”

Sylvia stares at him for a second, then shakes her head and says, “You talk about this individual as if he’s not only a first-rate artist, okay, but as if he’d moved beyond that status. Like he’s some kind of visionary. You might disagree with my phrasing, but your whole group here feels a little cultish. I don’t mean to be insulting. I’m just asking why, until very recently, I’d never even heard of Terrence Propp? Never seen any of his work. I’ve never read an article about him. Never heard him mentioned anywhere in the media. And I’m not exactly an uninformed person.”

Gaston keeps a poker face and says, “We each come to Propp when we’re ready. That’s the beauty of the whole phenomenon.”

“That’s an answer?”

“I don’t expect you to understand yet,” he says. “And I may have made a very large mistake bringing you in ahead of time—”

“I don’t want in.”

“But in fact, you made a statement earlier—”

“A statement?”

He looks at her oddly, squinting his eyes.

“You said you had something that belongs to Propp.”

Did she say that? Sylvia can’t even remember now, but she must have. She doesn’t want to mention the Aquinas prints, so she shakes her head and says, “I thought that would get me a name, you know. I thought it might buy me a connection. I lied. And it worked.”

It’s clear Rory Gaston doesn’t like this answer.

“I’ve just seen a few things,” Sylvia says. “I’ve just discovered a few pieces. Yesterday. For the first time.”

“And where,” Gaston says, “was your first exposure?”

Sylvia hesitates, then says, “Excuse me?”

She feels him tensing up.

“You just said you’d never seen any of Propp’s work until yesterday,” Gaston says.

Sylvia nods.

Gaston’s hands come out into the air, questioning. “Where did you see Propp’s work? Where were you?”

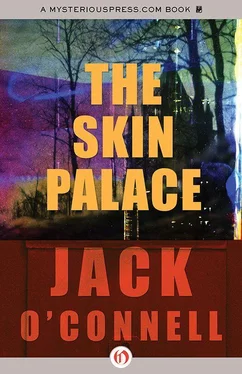

She meets his stare and says, “The Skin Palace.”

He looks confused. This wasn’t the answer he was expecting.

“Herzog’s,” she says. “The movie theatre.”

“You saw a Terrence Propp in Herzog’s?”

Sylvia nods.

Gaston starts to shake his head and says, seemingly to himself, “I’ve made a huge mistake here.”

He walks to the door and unlocks the bolt, pulls the door open, turns and stares at Sylvia.

“What’s the problem?” she says.

He doesn’t say a word, just stands next to the door waiting for her to leave.

And the light-headedness returns, as if carried in on a draft of air from outside.

She gets up, a little wobbly, moves across the room and says, “Look, I’m sorry if I—”

“Just get out,” Gaston whispers, “before someone sees you in here.”

The back door is open. Sylvia comes into the kitchen and sees the bottle of Dewar’s, uncapped, sitting on the counter. She can hear the TV from the living room but she can’t make out the words. She takes off her coat and hangs it over the back of a chair, walks down the hall and finds Perry sitting on the edge of the old leather hassock that had been her mother’s. His suitcoat is tossed on the couch. He’s leaned forward staring at the screen, a fogged-up water glass between his hands. His hair is a mess and his shirt is half-untucked. He’s squinting at the TV screen, looking like he’s trying to decode hieroglyphics.

He’s so intent, she feels like she shouldn’t interrupt him, like he’s in a state of frantic prayer. She’s never seen him looking this way in front of the television. Usually he’s just the opposite, close to narcoleptic, one eye on a game that he lost interest in a half hour ago.

“Perry,” she says from the doorway.

“Jesus,” he flinches and rears back, tossing some of his drink into his lap.

“Shit,” he yells, standing up, trying to get his balance, pulling at his pants with his hand.

Sylvia starts to go to him but then she gets a look at his face and stops. He’s furious. His head is bobbing in that way that she knows means trouble, means he’s beyond annoyed and deep into a full-blown temper tantrum. They could have some wall punching any minute.

Читать дальше