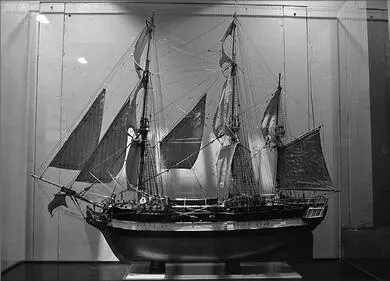

The World launched a subscription. The money poured in. Children walked the thirteen miles from New Westminster to Vancouver and gave their carfare for the Pauline Johnson machine gun. By August 1915 the World had $1,000 (more than the annual wages of most working men), which it sent to Minister of Militia and Defence Sam Hughes. The manager of the World was delighted that Lt. Col. Tobin of the 29th Battalion would receive a gun for his “gallant corps.” Would Tobin see that the gun bore the name Tekahionwake? Tobin wrote that American munitions manufacturers could not deliver the gun before January 1916; the Russian and Canadian governments took the firm’s total output, but he hoped to obtain two guns before the battalion left for the front or certainly shortly afterward. He promised to engrave Tekahionwake on one and send a photo, but in December 1916 the battalion was still without its Tekahionwake. In December 1918, the manager of the World wrote to Tobin wondering whether “the Tekahionwake which we gave to the 29th” could be returned to the World ? “We are all so proud of our British Columbian men,” he wrote, “that I am hoping the story of the war, from the British Columbia standpoint — and with special reference to the exploits of the BC units — will be collected and become a textbook in our schools.” In July 1920 the World regained possession of the gun, and showed it with a poster saying it was first fired at Kemmel Hill, Belgium. During a raid, it jammed and Corp. Snowden tore the red-hot gun apart, fixed the feed-wheel pin, reassembled the gun, and fired again in less than ninety seconds. At St. Eloi, the Tekahionwake was manned by Ptes. McGir, Owen, Bourke, Annandale, Cooke, Davidson, and Williams (all killed later). At Ypres, three tripods were shot from under her.

I lay out my scraps of research — the haunting trees, Johnson’s walks to Siwash Rock, the things she left in her will, her stories (from Skwxwú7mesh Chief Capilano) of the Sagalie Tyee, the strange spellings of words in the Skwxwú7mesh dictionary, the 7 to be sounded as a glottal stop like oh-oh , the xw sounded like whispered wh in what . Puzzling over how the Skwxwú7mesh language might talk about the Sagalie Tyee, I find wa lh7áy’nexw is a Skwxwú7mesh word for spirit . The dictionary gives no English pronunciation. I’m left to imagine what sounds I can. Kwelh7áy’nexw translates as spirit of the water. Spirit touches one and one goes numb : from the word tení7i7. To go on a spiritual quest for power: ts’iyíwen. Nexwslhich’álhxa is a spirit who cuts people’s throats, whereas ch’awtn is a spirit helper. Siw’ín’ is a spiritual power exercised through words, while sna7m is a spiritual power exercised through dancing and singing . I let the words figure my tongue. As though words were boxes, and, lifting their wriggling lids, I could find moccasins to slip on, become other than what I am: a taster of letters, a chaser of whiffs humming with threads to other alphabets, echoing glimpses beyond words, always a beyond — an end to a rainbow that flits away to a creak or a moan, a chortle, a rattle, a knocking heartbeat, gutwrench, the thousand bitmaps wired in my eyes from born-into wars owners ancestors conquerors cities. As though I could wear them like masks. Tree — Spirit — I tie with tongue taps, certain they exist somewhere with Forest Skwxwú7mesh Self Moccasin. Laces evaporate leaving foot tied to ear, mouth to armpit, eyes all knees and elbows adrift in my house of mirrors. Tap tap tap along the rhythms. Anyone there?

Approaching, in June 1792, the long tongue of land that separates Vancouver’s harbour to the north from its boating and beach playground to the south, Captain Vancouver met Chief Capilano’s ancestors, who, he wrote in his Journal of Discovery, “conducted themselves with the greatest decorum and civility,” and presented him with “several fish cooked and undressed.” They “shewed much understanding,” Vancouver thought, “in preferring iron to copper.” The welcoming party paddled alongside Vancouver’s ship

as it headed between Homulchesun on the north shore and Whoi Whoi on the south. Twice they assembled their canoes for ceremonial acts whose meaning remained “a profound secret” to Vancouver and his men. Afterward they showed even greater cordiality and respect to the pale-faced newcomers.

The secret was revealed by Qoitchetahl, secretary of the Skwxwú7mesh Indian Council in 1911, who told the city’s archivist his people believed “a calamity of some sort would befall them every seven years… Capt. Vancouver came in a seventh year… When strange men of strange appearance, white with their odd boats, arrived, the wise men said ‘this may be the fateful visitation’ and took steps to propitiate the all-powerful visitors” with the white eiderdown scattered at festival or potlatch houses. As Vancouver arrived, his people “threw in greeting before him clouds of snow-white feathers which rose, wafted in the air aimlessly about, then fell like flurries of snow to the water’s surface, and rested there like white rose petals scattered before a bride.” That painted icon Johnson chose not to be, preferring instead to hail the world from the stage with a “cry from an Indian wife” bidding her husband, go to war: “by birth we Indians own these lands, / Though starved, crushed, plundered.”

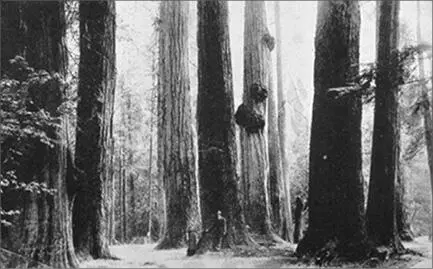

It’s not the immensity of Lions but the immensity of Twin Sisters that rules Vancouver’s antlike scurryings. The immensity of trees and the immensity of sisters. Pauline was passionate, spontaneous, and generous; her sister Eva was dutiful, frugal, and practical. They argued and wrangled all their lives about Pauline’s unseemly stage career, about her raffish friends, about her loans to finance recital tours, and about who was the better teller of Iroquois history. Right up until her death, they quarrelled about why she must be buried in a gloomy forest of incessant rain far away from her homeland. They even fought over whether you had to wear a raincoat in Vancouver: Eva said you did; Pauline said you didn’t.

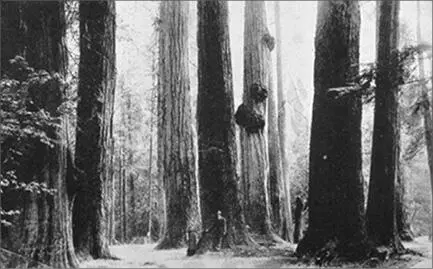

The Seven Sisters in Stanley Park were Pauline’s daily haunt. “In all the world there is no cathedral whose marble or onyx columns can vie with those straight, clean, brown tree-boles that teem with the sap and blood of life,” Johnson wrote of her trees,

“no fresco that can rival the delicacy of lace-work they have festooned between you and the skies.” When she was too weak to walk she drove to the park in an open carriage. There must surely be some trace of them in the Stanley Park forest — women who dare, women who stand for all to see, and one woman especially, who wrote, “I love you, love you… love you as my life. / And buried in his back his scalping knife.”

With my sister I set out along the seawall from Third Beach, the west wind forcing us to double over like question marks. Fortunately the tide is out, leaving a good stretch of bare rocks between us and the crashing waves that have chucked piles of sand and seaweed along the pavement. We hug the edge of the forest seeking lee from the wind till we get to the steps up Ferguson Point bluff. Wind blowing away our conversation and chilling us right through our rain gear, we head across the grass to Johnson’s shrine and burial place not far from Sl’kheylish: standing-up-man rock. The shrine’s rough-hewn stones, enfolded in the shadowy roots of seventy-year-old forest, form a cairn holding a carved relief of Johnson’s face above a pool catching rainwater. And it now comes to me that we’ve made this pilgrimage in a kind of amazing cosmic rhythm during the same week in March that Johnson died one hundred years before.

Читать дальше