On the SS Diderot Sigbjørn the imagined novelist writes that his character Martin wanted above all things to be loyal to Primrose in life and even beyond life, loyal to her beyond death . Primrose, he would write in La Mordida , without whom he could see nothing. At least nothing out there. In Haiti, she’d seen it coming: the breakdown in Cassis — he tried to strangle her — and was confined to the American Hospital of Paris. In Rome he was again confined to a sanitarium, and tried again to strangle her. He spent months in Brook General and Atkinson Morley’s in London before his final attack on her, wielding the broken neck of a gin bottle she’d smashed trying to stop him from drinking, till she fled and he downed a bottle of sleeping pills.

Sigbjørn and Primrose Wilderness disappear from the manuscript of La Mordida carefully typed by Margerie, which she gave to the archive in 1986, two years before she died. Someone has made Sigbjørn and Primrose back into Malcolm and Margerie, each speaking in first person, as in a stage play, their dramatis personae announced as chapter titles, their voices reading from their notebooks. But Sigbjørn and Primrose lived on in October Ferry to Gabriola , where they were neighbours of the imagined reclusive once-successful criminal lawyer Ethan Llewellyn and his imagined wife Jacqueline: sometimes when Jacqueline felt like talking to Primrose they’d take his instrument down to the Wilderness’, who lived in a similar cabin in a similar bay about three quarters of a mile down the beach, and with Sigbjørn, who was an unsuccessful Canadian composer, but an excellent jazz pianist. They’d all have a jam session: singing the Blues à la Beiderbecke, the Mahogany Hall Stomp and heaven knows what. Or they’d play Mozart, after a fashion.

If I, No Reply, write of Christine Stewart,

inside I lives the now Christine next to long-ago Christine who cut pens from goose quills, the Christine who wrote, The servant who receives fewer gifts from her lord is less obliged in his service , the Christine of Pizan, who built a city for the giftless. Bridges and rivers of Christines enclose I. Crossroads of Christines play I. A scriptorium writes I among riverbanks, ancestors, Christine villages, Christine tribes, as deserts and wars of I. The I is nothing. Can never be nothing . I and Christine run through lanes, alleys, arcades, shops, bars, offices, cemeteries. We intersect in Cul de Sac Cafe. We despise its twisted stairs to Pink and Sticky but own them anyway: A pronoun cannot but witness its world . The doorman poses like the exterior of an acoustic muscle . We have no money. We back out through our cloth music as in beat and grief of an unlivable category . In room after room we find men, women, and dogs sleeping. Space does not go on forever , she tells I, It crushes. It curves the domain in its foreclosure . Finally I and Christine jump roof to roof like terraced rice fields to a regulatory nowhere . Watch out for the doorman, she warns, he’s everywhere: an unthinkable distance that folds you up like a tight square .

We write plays and perform them in the street. I plays she and she plays doorman. We have no money. To make nothing. To become nothing , she tells me, I became I . We squat in Other People’s Houses while they work and shop. We cannot rest; their I-beds poke into us. We run to the not-town. I is flooded. I is rapt , she says, and usually chained to the Human . Throw these categories in that ditch.

We must be mute again, she says. Not like fields and trees but in a giant muteness, a huge forgetting of tiny chattering categories. We must flood and drown. We’ll outnumber. We’ll dump the churches, the lording of property and marriage. We’ll shit where we want and our shit’ll blossom the soil. We’ll roam with beasts and fuck whoever, whenever, wherever. Our babies’ll grow huge and strong playing in their volcanoes of shit and mud. We giants’ll be exuberant and solitary and generous. We’ll roam the whole Now. Lightning sky-clap will wrench our muteness, our stumble and stutter, to avalanche of words. Wrench us to song-grapple.

Here we come to Underbridge, Christine continues, the unwhere of the regulatory nowhere, the unpromise of the right-direction automobile. Here, in Between, we radiate and compose ourselves as nextness in a vast dense musicality of other dreaming unpromises. Ravens, coyotes, homeless, Big Gulp, toxins, free doom — we read unminded. Quilt under bridge. Seven men under bridge. Broken CD, Metro News under bridge. Shame, Cold, Boredom — language and languish under bridge where I and Christine build cities for the giftless.

for Pauline Johnson Tekahionwake

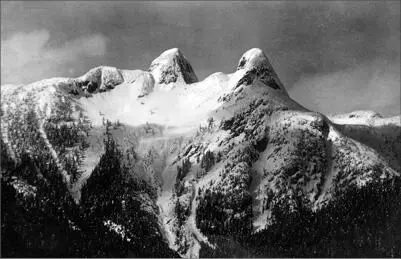

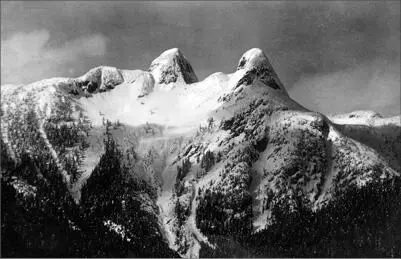

Drive north on any of Vancouver’s main streets, and the forested hulks of Grouse and Seymour Mountains lunge up a wall as your road disappears over a cliff edge into the inlet. In East Van the hulks dwarf false-fronted wooden stores reminiscent of frontier trading posts, laced together by electrical wires on leaning cedar poles. In the West End they loom over tower blocks and corporate skyscrapers, reminding the busy city, in its antlike toings and froings, of all it is not and can never be. All the more so because even the immense, implacable blue-green hulks are superseded by their crown, a pair of snow-covered peaks that Vancouverites fondly call the Lions.

With the cables of its Lions Gate Bridge, swooping from pylon to pylon, Vancouver ties itself to the Lions’ immensity.

Logs of wood and stumps of trees innumerable, Captain George Vancouver wrote in 1792, staring at driftwood on the delta of the Stó:lō, the river at the foot of these mountains, which did not lead him to the Northwest Passage. Trees, trees, and more trees on the wall of peaks blocking his way. Up the coast in the traditional lands of the Skwxwú7mesh, he found a stupendous snowy barrier lurching from sea to clouds and spewing torrents through its rugged chasms. He logged the weather: dark, gloomy, blowing a southerly gale, which greatly added to the dreary prospect of the country. Desolation Sound he called some of the coast: forlorn gloomy forests pervaded by an awful silence, empty of birds and animals.

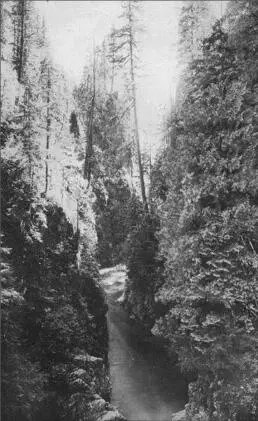

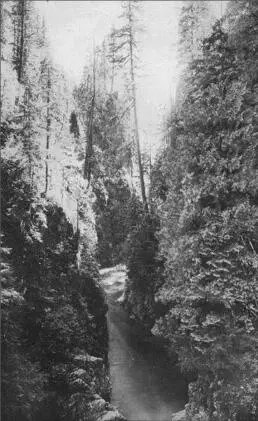

Trees haunt the city: the old giants whose feet spanned a cart and horses — their stumps slimy with moss — still lurk in the salal and ferns of Stanley Park or up the slopes of Grouse Mountain in the Capilano Canyon, where they feed the roots of new giants several arm spans in girth. Their distant tops creak and moan in the wind. Myriad spiny branchlets of fir and long, drooping fronds of cedar catch shafts of sunlight and rake tatters of fog from the ocean. The air drips. Trunks, limbs, moss soak up the grind of city planes and cranes, holding in their cavernous understory the rush and trickle of the Capilano River, the peep of a nuthatch, the snap of a falling branch, and, high above, the combing of wind, the chortle of a raven.

Up above, high — sagalie, in the Chinook jargon Pauline Johnson used with Chief Joe Capilano, recording his stories of the Skwxwú7mesh people and the Sagalie Tyee. I imagine Johnson searching like I was for stories, not from invaders, but from here, stories from the first people of the immense mountains, the giant trees, the talking ravens.

Читать дальше