The snow-covered Lions are not lions to the Skwx-wú7mesh people; they are the Twin Sisters who were lifted to the mountaintops by the Sagalie Tyee. It was they, so Johnson records in her Legends from Chief Joe Capilano, who brought the Great Peace between the Skwxwú7mesh and the Haida by the simple act of inviting them to a feast. Another legend tells how the Sagalie Tyee sent his four giants to challenge a swimmer, claiming they would turn him to a fish, a tree, a stone if he did not give way to their canoe.

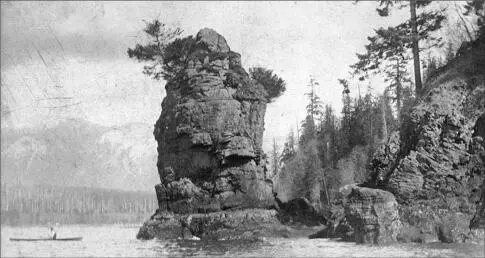

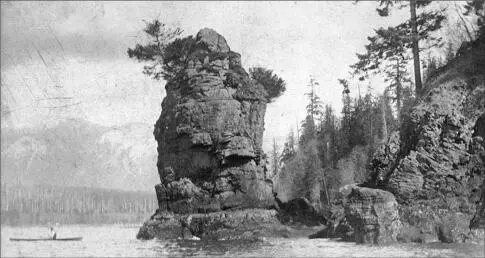

Back and forth and right toward the giants’ canoe he swam so his child would have a clean life. The Sagalie Tyee made him Sl’kheylish (standing-up-man rock) to remind everyone: defy everything for the future of your child.

Thanks to the Sagalie Tyee, Shak-shak the hoarder suddenly found himself a two-headed serpent, one of his mouths biting the poor and one mouth biting his heart. He who pierces the serpent’s heart will kill the disease of greed — so said the Sagalie Tyee. A young man of sixteen remembered those words and brought down the monster.

A young woman could get help, too, from the Sagalie Tyee, if she wanted to know which suitor really cared for her. What if she were looking for other things? Like stories that had grown with the forests. Stories of women who dared, women who blazed trail? Women who spoke? Would the Sagalie Tyee come to her aid?

The front desk casually mentions a pair of Pauline Johnson’s moccasins held somewhere in the library, she’s not sure where. A Special Collections librarian says she’ll look into it and disappears to inner chambers. Some time later she returns with a large metal-cornered box. We have no provenance for these, she tells me, unfolding tissue paper around a pair of pale leather moccasins covered with beaded flowers and bands of woven grass, the soles smooth as the bottom of a foot. Their ankle-high cuffs flop over next to tangled delicate lacing. Lack of provenance meaning, I suppose, that someone could have found a pair of moccasins in Johnson’s possession when she died which actually belonged to someone else — her sister, say, or a friend — and mistakenly passed them off as Johnson’s, or even that someone claiming to be a friend of Johnson’s had given them to the library when in fact they had belonged to the friend’s grandmother and never been touched by Johnson. I try to convince myself of this, but I’ve opened a box I can’t close: I’m certain they are Johnson’s. She’s supposed to be wearing them in this photograph, the librarian explains. She retrieves from an envelope a photocopied picture of E. Pauline Johnson Tekahionwake in her Mohawk stage costume, which she made of buckskin, and we see her as through a window smoked up by a house fire, moccasins illegible.

In 1909 she retired from the stage at forty-eight to a two-bedroom Vancouver apartment three miles from Sl’kheylish, one of her favourite destinations in Stanley Park. Like everyone else she called it Siwash Rock, though siwash was an insulting term for an aboriginal person.

For twenty years she’d been Canada’s most famous author (known throughout the English-speaking world), constantly touring and living in hotels. Now her days turned around a small apartment on a treed street in a town clinging to the far edge of North America, a town barely keeping its own against wind and sea and the forested mountains looming in its face. Yet here she found something grander than ever: her Cathedral Trees. Every day, heedless of the rain or sea soaking her clothes, she would walk to Siwash Rock, and then to the nearby Cathedral Grove, one red cedar and six Douglas firs from the old-growth forest, people called the Seven Sisters.

To support herself without income from stage performances, Johnson wrote stories for Mother’s Magazine and Boys’ World , stories like “The Wolf Brothers,” “The Silver Craft of the Mohawks,” and “The Potlatch.” Her friend, Chief Capilano, whom she’d met at Buckingham Palace, came to visit, sitting in silence at the round oak table from her father’s house. After several visits he began to tell her stories she would retell as “Legends of the Capilanos.” Lionel Makovski of the Vancouver Daily Province began paying her seven dollars a piece to publish the stories in his weekly magazine, adding photographs to make them and Princess Tekahionwake his star attraction; elsewhere the paper had called the chief an agitator and blamed him for disputes and uprisings. Johnson then could not meet his deadlines; she cancelled appointments without notice; Chief Capilano died; and breast cancer spread into her right arm. Makovski himself became her writing hand as she dictated the stories from her couch.

An unsigned document in the moccasin box says that Makovski earned a lot of royalties from Johnson’s legends. He was a member of the trust that gathered them into a book to raise funds for her living and medical care. More than ten thousand copies were printed at that time, and the book remains in print. Johnson left Makovski the copyright to Legends following her death in 1913, as well as the moccasins she wore on her first trip to England, he perhaps then leaving them to the library.

She left her pens and the copyrights to Shagganappi and The Moccasin Maker to her manager and stage companion, Walter McRaye, who had started his career reciting Drummond’s habitant verses and who later did hilarious impersonations of celebrities. Dink, she nicknamed him. During their long journeys on boats and trains and stagecoaches, they invented together a family of travelling companions: “the boys” — four of them — who took their mattresses along and slept on the hat racks, and from there played tricks and commented on their friends. At Steinway Hall in London, the boys bought four tickets for Pauline and Dink. They amused themselves with a cat called Dave Dougherty, who slept in Johnson’s dressing bag; a bug called Felix Joggins, with his very trying wife, Jerusha; and a mongoose called Baraboo Montelius.

In 1915 the balance of the proceeds from Legends , after paying Johnson’s debts, was divided between McRaye and Johnson’s sister, Eva, who then divided her share between the cities of Brantford, Ontario (near Johnson’s ancestral home), and Vancouver, sending $225 to the World newspaper to spend on something of assistance to the arts or literary life of the city. Mr. Nelson, the manager at the World , was puzzled as to what to do, but at length hit on the idea of purchasing a Pauline Johnson room at the hospital which could be devoted to care of artists, actors, poets, newspaper people, and “others of allied interests who might be in hard circumstances (a not unusual condition in these occupations).” He was then “very much moved” by reading about the city’s 29th Battalion at the front, who were “lamentably short of machine guns where the enemy was well equipped with them.” The Vancouver boys seemed to be fighting with their bare fists. Why not buy a gun?

How very easy it is to rouse individuals around a sentimental cause. Only to suffer slow and miserable deaths or violent and brutal ones in the Great Ongoing Wars of humanity against humanity and humanity against the earth. Buoyed up by inner spirit or driven by drugged imaginations, people launch into their ventures with little idea of where they’ll lead. Or they launch in knowing all too well where it will end: their fate. Yet boundless and unpredictable beginnings save the world from its normal and natural ruin. Thus writes Hannah Arendt: in the fact of natality lies the root and faculty of action. We act, we speak, and each time make a beginning toward the possible, just as we entered the world from our mothers’ wombs.

Читать дальше