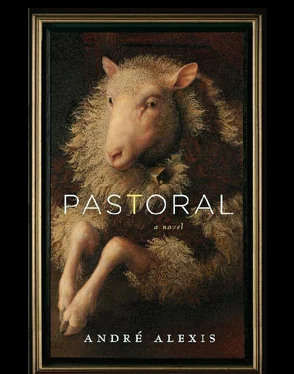

Around six o’clock, the newlyweds were ready to leave. Their time together as husband and wife had begun. Elizabeth wanted a last look at the land that was home, before she left for Pearson Airport in Toronto, so she quietly walked away while Robert said goodbye to his friends. Somehow, a few of the sheep had strayed from their pen. They stood eating grass at the periphery of her wedding, as if curious about the goings-on, but not too curious. They kept their distance. Elizabeth walked toward them, away from the reception, unobstructed now that she was in normal clothes. The sheep were so used to humans, they scarcely reacted to her approach: a little bleating, a shifting, as if to make room

for her, and then they were quiet, thoughtfully eating the grass and weeds.

As she passed them, it struck Elizabeth that she had always loved sheep, but she had rarely paid much attention to them. They were, simply, a part of her world. She stopped, turned back and stood looking at the sheep for a while: dirty fleeces, fat-looking flanks, delicate legs, almost invisible tails, the smell of them, the weight of them in the mind so different from the weight of cows, say, or dogs. In her imagination, it was as if one could pick a sheep up with one hand, like raising a cloud. Not true, of course, not true. They were beautiful and solid and having taken their beauty in, Elizabeth walked on toward a rise in the land from which one could see all the way to Barrow, its houses.

Elizabeth was alone for no more than a few minutes before Father Pennant approached.

— It’s beautiful, he said. Isn’t it?

Elizabeth looked out over southern Ontario, the land beneath them, oddly misshapen squares of dark green, black and yellow. Here and there were farmhouses and barns. To one side, there were the woods. And beyond, the crab shape of a small town: Barrow. This was who she was. Had her parents lived, her destiny might have been different. She might have had these feelings for Strathroy or Ottawa, Windsor or Thunder Bay. But her parents had died and this was the place that had taken her in, and she could imagine, finally, that in death the land would take her broken body and care for it as it would for all bodies that had walked the earth.

— Yes, she answered. It is beautiful.

— Sometimes, said Father Pennant, I think it’s all we have.

— I don’t think it’s all we have, Father.

— You’re right, said Father Pennant immediately. You’re right. There’s more. Are you enjoying your wedding?

— It feels a little strange to call it enjoyable.

Father Pennant laughed.

— I find weddings strange too, he said. No … mysterious is a better word. They’re mysterious. All the sacraments are, when you think of it. They’re moments when the grace of God touches the earth. I mean, that’s what the Church teaches.

— You don’t believe that? asked Elizabeth.

— Yes, yes, of course I do. But it’s still mysterious, however you describe it. I mean, you don’t have to bring God into it. The very idea that two people choose to get married in the first place is mystery enough.

— Yes, said Elizabeth. It is mysterious.

They spoke for a few more minutes, before Father Pennant wished her a happy honeymoon. He was going to walk to Barrow, to work off some of the wonderful food he’d eaten.

— It’s one of the finest weddings I’ve been to, he said.

He walked away, wishing her all the best in the life to come with her husband and — did they want children? — children.

Elizabeth stood alone for a moment longer, thinking of Father Pennant’s words about the world being all we have. Well, if that was true, if the land was all — no God, no love, no others — she could still be happy because, in the end, everything came from the land, from the smallest thing to, maybe, God Himself. Anything you took away, the land would give back. Or so it felt to her, at that moment, and she walked back to the reception, tired and content.

Yes, she did want children.

The next day, the very next day, the new life would begin in earnest. It would have its problems, of course. She was not certain she could remain married to Robert Myers, that she would be Mrs. Myers for long. But she put her doubts aside as she returned to the field and to her various families.

Father Pennant went on his way back to Barrow. He passed through the woods, its darkness a little intimidating, before coming out by the highway that looked down onto Barrow. His thoughts were confused. Had he really asked Elizabeth Denny if she didn’t feel Nature was all? He should not have. (Nor should he have had the feelings he fleetingly felt for her. For the briefest of moments, as he asked Elizabeth about children, he had imagined the salt taste of her, the feel of her tongue on his, the animal there -ness of her body.)

Since the death of Lowther Williams, he had become so passionate about his study of the land around Barrow that he sometimes lost sight of the world beyond, of God the creator. Even now, at the thought of ‘God the creator,’ he felt an unexpected twinge of mistrust. Mistrust? Yes, ‘mistrust’ was almost the word. Take the implications of Lowther’s death, the implications of a ‘compact’ with God. He supposed that some would have taken Lowther’s death as a manifestation of God’s mercy or, at very least, His will. That is, if they accepted that God had interrupted His infinite discretion to kill Lowther himself. For a while, he’d preferred to think of Lowther’s death as a coincidence — perhaps, even, an unconsciously made decision on Lowther’s part, a suicide carried out unawares. Now, however, he admitted to himself that, yes, it was possible for the infinite to concern itself with the death of a being. Perhaps it was even right. Perhaps if Lowther or any of his male antecedents had lived beyond the age of sixty-three, there would have been catastrophic consequences. So, Lowther’s death had been justified.

But if so, that made any ‘god’ who carried out the execution a caretaker, a gardener pulling weeds. And as it was with Lowther, so it was with loaves and fishes and the parting of the Red Sea. God, ultimately, was useful. But why call Him ‘creator’? Why should we say God created Nature rather than, as the ancient Greeks believed, Nature created the gods, that ‘god’ was subject to Nature’s laws and interdictions? It was easier to believe, easier for him to believe, anyway, in the rules of Nature binding God rather than the other way around.

Honestly, that sheep couldn’t have done better if it had been divine.

Christopher Pennant knew, or felt, that his thinking was suspect, but he could do nothing about his thoughts. He was again experiencing the struggle for faith he’d experienced as a seminarian. And, yet, he was not unhappy. More than that: as he walked home he was in the very best of moods, as joyful as if a storm had passed and the world was restored to its entrancing self. The early evening sun was still bright, though the clouds in the distance were reddish and darkening. The air was clean and smelled of the woods, of the fields, of the world itself over which a light breeze blew.

He thought again of the sheep he’d encountered in Preston’s field. He then immediately thought (again) of Lowther and then of Lowther’s prayer book. The prayer book, which had once belonged to Lowther’s father, had had every prayer crossed out but one. The one prayer left, a perverse prayer for death, had itself been crossed out by Lowther, almost certainly in the days when he had believed God had abandoned him. So, on the dresser in what had been Lowther’s room, there was an entirely useless prayer book. Useless? No, not useless. In that it served as a memento of Lowther, Father Pennant could not bring himself to throw it out. There, you see? There was an example of spirit (Lowther’s spirit) adhering to a thing (the prayer book). You could use Lowther’s prayer book as proof that the world was more than material, couldn’t you? No sooner had he asked himself this question, though, than it was dismissed. The only value the book had was in him, Christopher Pennant. It was not in the book itself.

Читать дальше