One day, when Lowther was unexpectedly called away and could not go with him to the old Stephens place, he warmly insisted Father Pennant explore the abandoned farm on his own. The farmhouse looked to be sturdy, though it smelled of wood that had rotted. The barn was ready to collapse on itself, as if a great hand had pressed down on it and burst its roof. Decades previously, the Stephenses had planted apple trees in a modest, ordered grove: thirty trees in tight rows, five by six. At a distance from the apple trees there were other trees (willows, birches and maples), tall, yellowed grasses, thistles, buttercups and an unexpected clump of purple lilac bushes that intoxicated with their perfume. A brook, a tributary of the Thames, ran across the property: narrow, four feet across, its waters clear as glass, its banks low and rounded to an overhang in places. In and around the brook: turtles, frogs and small fish that swam like living slivers of birch bark. Beyond the brook, a wide, open field, alive with grasshoppers, crickets and mice.

As it had done when he was beside the Queen, the water held Father Pennant’s attention for a time. It ran pure and quick, looking like a strand of clear muscle. And it seemed to Father Pennant as if he could have lifted the brook out of its channel, as he would ligaments and fascia from an animal he had dissected. What was it about the streams in this part of the world?

Father Pennant stepped across the brook at its narrowest point and began to explore the rest of the field. The land was so alive, it felt as if he could have put a hand down into the tall weeds, without looking, and picked up a living creature. And he was thinking how much he would have liked to hold a deer mouse or a shrew in the palm of his hand when he heard a click like the sound of a twig snapping and a cloud of gypsy moths rose from the grasses.

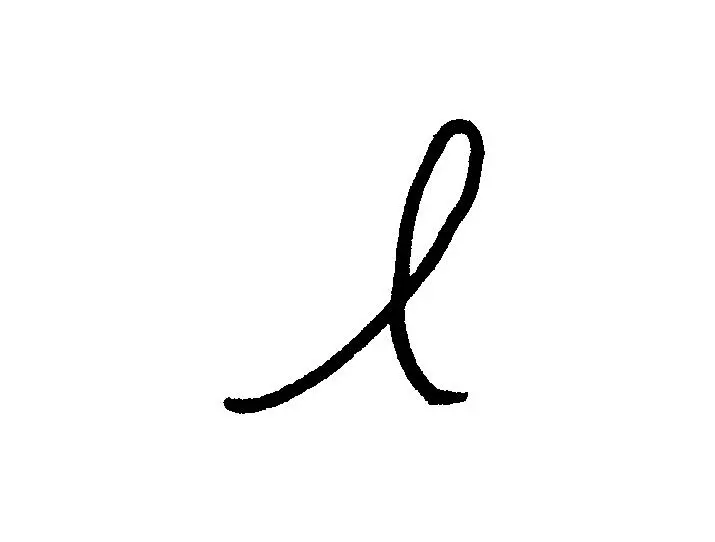

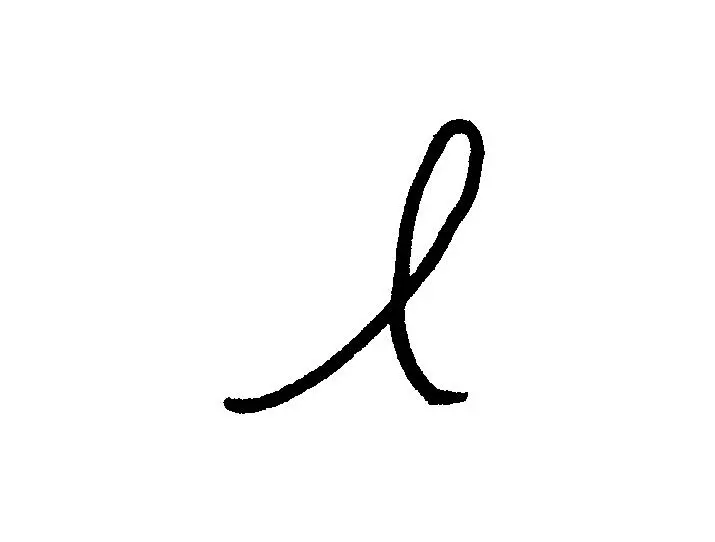

That in itself was strange. Gypsy moths usually ate tree leaves. They were the last thing one would have expected to find in the tall grass. But stranger still, the moths flew up as one and formed, with their wings and bodies, two distinct shapes. First the moths aligned themselves in such a way as to create, from Father Pennant’s perspective, an elongated loop:

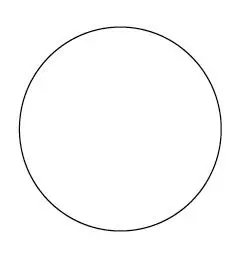

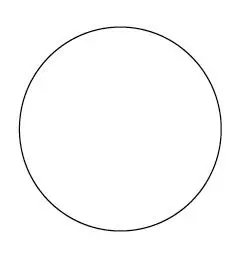

There could be no mistaking this for a random configuration. Then, as if to confirm that very thought — that they had purposely created a loop — the gypsy moths dispersed then regrouped to form a flawless circle:

They fluttered in formation for some time before falling to the ground.

Father Pennant had never seen nor ever heard of anything like this. He was at first puzzled, unable to quite believe what had happened. He had been surprised by the first pattern the moths made (the loop), but he was, as time passed, frightened by the circle they had formed. He could not help feeling that such a perfect circle had some special meaning, a meaning meant for him alone, but he couldn’t for the life of him imagine what it might be. It was as if some being had spoken to him in an extraordinary language and expected him to understand. But, if so, who had sent the insects to ‘speak’ with him?

No, there had to be something wrong with the moths. He looked about the field, but though there had been quite a number of them, Father Pennant could find none on the ground. Here was another puzzling thing: it wasn’t possible for so many moths to vanish so quickly. Thinking that deer mice must have eaten them all, he gave up his search for moths after half an hour, disappointed. He drew what he had seen: Lymantria dispar , brownish-grey with a brown fringe at the bottom edge of its wings when the wings were closed, its antennae like two delicate, minuscule feathers, its body a narrow, umber cylinder with six thin white stripes that transversed it at almost regular intervals. Perfectly common. They had been gypsy moths, no doubt about it, despite the strangeness of their behaviour.

Or had he been dreaming? He waved his right hand before his eyes. And saw it. He cleared his throat and heard the sound. Aside from the fact that he had just witnessed something unaccountable, he was — or felt he was — as normal as could be: a Catholic priest in Barrow at a time of year — mid-spring — when gypsy moths are about.

As he always did when he was bewildered or thought about God’s grandeur and mystery, he kneeled down to pray. He kneeled in the weeds, among the insects and rodents, and prayed for enlightenment. What were his duties, now that he had been given a vision?

There was great comfort in prayer. It was not so much that he felt the presence of God when he prayed, though he did at times feel His presence and that always brought him peace. It was that kneeling — head bowed, fingers interwoven and held on his chest — immediately brought to his mind all the times he had surrendered to the mystery that was the world and to the mystery that was God. Comfort came from the continuity of submission. Kneeling, praying, he was himself at his most open and at his most genuinely human: ignorant, hopeful, humble in the face of the unknown.

The man who had gone to the old Stephens field was, for a time, different from the man who left it. The new Father Pennant was rattled and uncertain. On entering the field, he’d believed he was getting to know the county and its people. Barrow and the land around it had struck him as marvellously new, but not mysterious in any metaphysical sense. The certainty that Barrow and Lambton County were ‘normal’ was taken from him when he saw moths flying in a circle, a fluttering hoop suspended in mid-air. But this uncertainty wasn’t certain either. As the days passed, he grew less sure that he had seen the moths in wilful pattern. The whole episode began to seem incredible and he was relieved he’d chosen to keep details of the day to himself. Lowther would almost certainly have thought him unstable.

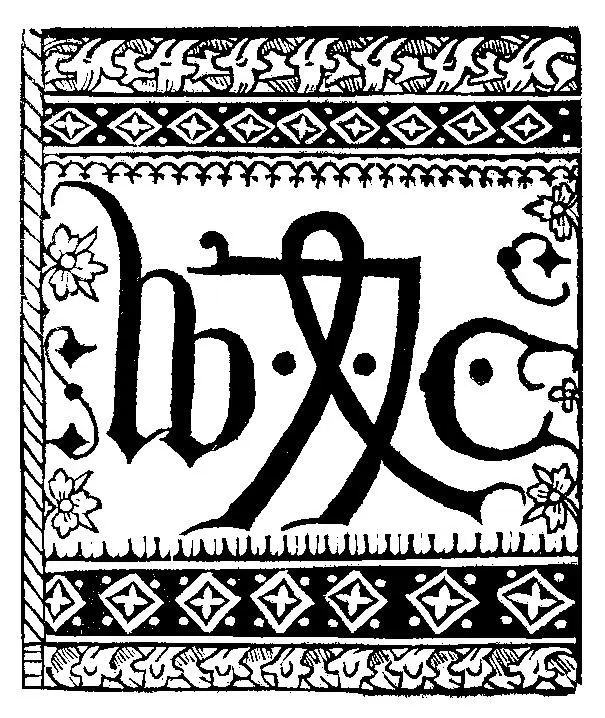

He might even have forgotten about the moths, but then, while collecting the mail one day not long after his episode in the Stephenses’ field, he found a postcard for Lowther. It was from Cartmel Priory, in England. On the front was the picture of an old church. But on the back, where a signature might have been, was a mark: a one inch by one inch square, with an element that reminded him of the loop the moths had made:

Father Pennant kept the postcard until evening when he and Lowther were at the dining room table. Lowther had, as usual, prepared a lovely meal — white fish, olive bread, lemons, capers, a vinaigrette, a tossed salad. He seemed slightly distracted, or perhaps more thoughtful, but it did not detract from his duties. (The rectory would smell of the olive bread he’d made, for days.)

— Lowther, said Father Pennant, a postcard came for you today. I hope you don’t mind, but I was struck by this lovely woodcut on the back, so I hung on to it for a bit. Do you know where the woodcut comes from?

Lowther took the postcard.

— Yes, he answered. This is from Heath, the man who was with me when we first met. He was adopted, but a long time ago he found out his real family’s descended from William Caxton, the owner of the first printing press in England. That woodcut is Caxton’s symbol.

— Oh. It looked like a rune.

— Nothing that exotic. Just a signature. You know, Heath and I have known each other since grade school. And he’s been using that woodcut for a long time. I don’t even notice how it looks anymore. It is beautiful, though, isn’t it?

Читать дальше