— Yes, answered Baddeley.

— Well, I forgive you, said Davidoff. Let’s not talk about this fit of yours again, okay buddy?

They sat down at their places. At the table with them were other literary lights. To Baddeley’s left, there was the aging son of a late, great Canadian writer. The son, corpulent, his face as if carved from pink and grey butter, was himself a writer, but not a good one. To the son’s left was his publicist, a woman who wore her hair severely pulled back. Her lipstick was of such a bright red and her face so heavily made up that she looked, to Baddeley, like a Raggedy Ann doll. To her left was a man with a hearing aid who smiled and said nothing. And to the left of the hearing aid was the hearing aid’s wife.

In all the faces around all the tables there was not one that brought comfort to Baddeley. Davidoff’s brought the opposite — a creeping despair at the thought that this man had once been his friend. And it was no doubt this incipient despair that further distorted the small world lodged in the throat of Fennel and Rue . Wherever Baddeley turned, things seemed slightly or even distinctly out of whack. At the table behind his, for instance, Margaret Atwood sat regally, her grey hair an afro of sorts, her cheekbones like half-buried golf balls. Nothing unusual there save that, after a moment, it seemed to Baddeley that there was something of the iguana to her, and no sooner did that thought occur to him than Atwood flicked out her pinkish tongue, the rest of her head as still as if it had not quite escaped from the wax in which it had been carved. Beside her, Graeme Gibson’s neck grew so that he resembled a stork with thick glasses. In fact, all the necks in the room seemed to grow and sway vegetally, save, three tables away, Michael Ondaatje’s. His neck shrank. His head bobbed up and down, looking like that of a strangely tufted raven.

Raggedy Ann’s shrill voice interrupted Baddeley’s reverie.

— There’d be no publishing in this country if it weren’t for people like me, she said.

And it was then that the sounds of the menagerie assaulted him: implements on porcelain, women’s laughter, the low laughter of their consorts and companions, the scraping of wood on wooden floors, and then coughing, shouting, and the clearing of throats. Here, faces came at him: Gowdy, Dewdney, Johnston, Lane. There, they settled back into the mire, anonymous again: Redhill, Crozier, Crosby, Toews. The lighting suddenly seemed sickly, the same colour as the excrescence from a garter snake. The hors d’oeuvres tasted of kerosene, and though the dinner was just starting, Baddeley had to leave.

— I’m going to be sick, he said.

— Well, don’t do it on me, said Davidoff. I just washed this sweater.

Baddeley rose from the table and made as casual an exit as he could. He said nothing to anyone, leaving Davidoff to do any explaining that might be needed. He went down the stairs to the tea room, as if he were going out for a quick cigarette or something equally trivial. He imagined each and every patron in Fennel and Rue watching him as he retreated but, of course, not one of them noticed his departure.

Outside, the sun had not quite set. Somewhere in the west — beyond Parkdale, beyond Brown’s Inlet — its reddish flash was almost gone. He was on Bloor Street near Christie. Looking east, the lights were bright and life seemed to quicken around Bathurst. Looking west, various shades of blue accumulated above the world, as if in a layered shot. To clear his mind, Baddeley decided to walk north to Dupont. He walked past Barton, Follis and Yarmouth. On one side of the street, Christie Pits, Fiesta Farms; on the other, Christie Station, and a mile’s complement of modest houses.

It seemed to Baddeley that his soul caught up to him somewhere around Yarmouth. He looked over at the Spin Cycle Coin Laundry — above which, five irregularly spaced windows gave life to the red brick — and felt all of a sudden the solace that comes from being both somewhere and nowhere. He thought of Avery Andrews in the middle of Parkdale, — that is, in the middle of a neighbourhood to which he’d had no evident personal ties. “God,” it seemed, was a drug that made company hard to bear.

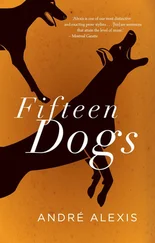

The months that followed were a time of unshakable ambivalence. Baddeley did what his publisher expected of him: two readings and a brief interview in which he tried, unsuccessfully, to say what his novel “actually” meant. He tried to use his inspiration to write poetry. But poetry, even bad poetry, was beyond him. No words meant for poetry would come. What came, despite his resistance to it, was yet another novel. To make matters worse, the novel that came seemed little more than a variation on Home is the Parakeet . This one, Over the Dark Hills , was set in the heart of an African conflict, its protagonist called upon to lead a herd of elephants over mine-infested ground to freedom.

There was, of course, compensation. Writing while he was inspired was tonic. The hours would breeze by as he wrote about lands he’d never seen, animals he’d never touched, and people who brightly lived in the recesses of his psyche. While writing, he did not care what he was writing. Novel, fable, poem, recipe… it was all the same. Disappointment came when he measured what he had written against his own ideals. First of all, there was, as far as Baddeley was concerned, the matter of fiction’s inherent inferiority. When he compared his work to the genuinely sublime (Goethe’s “Metamorphosis of Plants,” say, or “Canto 3” of the Inferno ), every word he’d written turned to ash.

Some time during the writing of Over the Dark Hills , at a moment when he was tempted to go back to the Toronto Western, Baddeley tried to reason himself away from his need for inspiration.

— I’m only writing fiction, he thought. I should be able to do this on my own.

It seemed to him that, having been a reviewer, he was familiar with “literature,” familiar with its rules, variations, and tropes. He could push a character through memories and places as well as anyone else, surely. Davidoff had been doing it for years, and a less inspired writer there could not be. But five chapters into Over the Dark Hills , Baddeley no longer knew where to take the story. Should he kill off one of the elephants? Should his protagonist betray his fiancée? And to what terminal was this novel heading? He tried to think his way through his questions, but he simply did not trust his own instincts and reasons. So, he was left with a choice: he could go on writing and re-writing scenes until one of them felt right or he could return to the Toronto Western.

He returned to the hospital and, for the last time in his life, Baddeley found the room he was looking for at once. Anxious that “God” would overtake him before he could speak, Baddeley cried out as he entered the ward.

— Please, he asked, what are you?

— I am, said God, what you cannot imagine that imagines you.

— But are you God?

— That word has a trillion meanings, Alexander. I am and I am not what you mean by it.

— But why use me ? asked Baddeley. What am I?

— You’re the peace I seek endlessly, said God.

— But I don’t think I’m as strong as Avery. I don’t think I can… The Lord interrupted him.

— You’re not Avery Andrews, Alexander. Your voyage is different.

— Do all writers go through this?

— Almost none of them do. Priests are much better at it.

— Did Avery see the kind of things I saw last time?

— Much worse, said God.

And took him to a terrifying place where he witnessed or, more exactly, participated in the murder of a family. Here, he was each of the three men who entered the family’s home just before dawn. He could smell the last of the previous evening’s supper. He experienced the killers’ sense of righteousness, their exhilaration, their fear, their contempt for the ones they slaughtered. But he was also the three members of the family: father, mother, and twelve-year-old boy. His mind was as if partitioned in six and every moment experienced by each of his six selves was inescapable. He could not cry out, neither in righteousness nor fear. He experienced death three times and then found himself in an empty room in Radiography.

Читать дальше