André Alexis

Fifteen Dogs

por qué es de día, por qué vendrá la noche …

— Pablo Neruda, ‘ Oda al perro’

why is there day, why must night come …

— Pablo Neruda, ‘Ode to a Dog’

AGATHA, an old Labradoodle

ATHENA, a brown teacup Poodle

ATTICUS, an imposing Neapolitan Mastiff, with cascading jowls

BELLA, a Great Dane, Athena’s closest pack mate

BENJY, a resourceful and conniving Beagle

BOBBIE, an unfortunate Duck Toller

DOUGIE, a Schnauzer, friend to Benjy

FRICK, a Labrador Retriever

FRACK, a Labrador Retriever, Frick’s litter mate

LYDIA, a Whippet and Weimaraner cross, tormented and nervous

MAJNOUN, a black Poodle, briefly referred to as ‘Lord Jim’ or simply ‘Jim’

MAX, a mutt who detests poetry

PRINCE, a mutt who composes poetry, also called Russell or Elvis

RONALDINHO, a mutt who deplores the condescension of humans

ROSIE, a German Shepherd bitch, close to Atticus

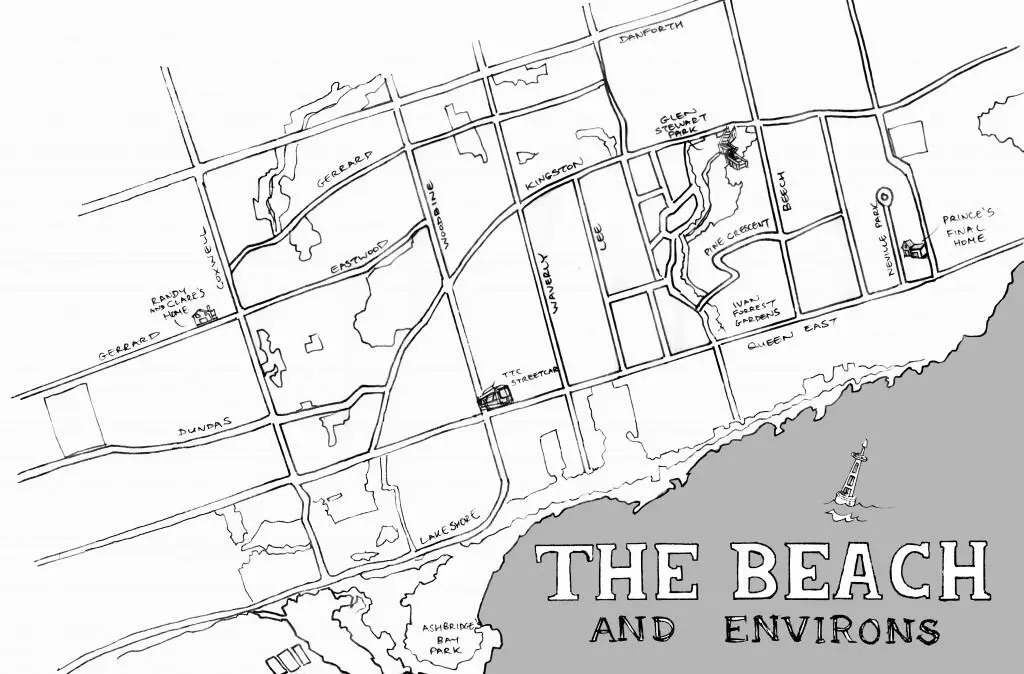

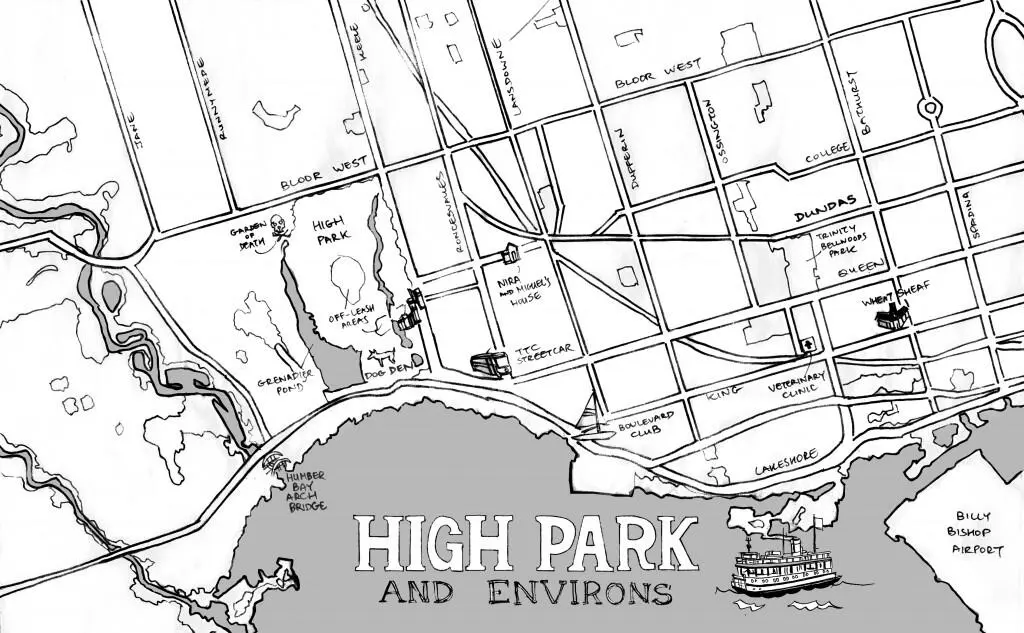

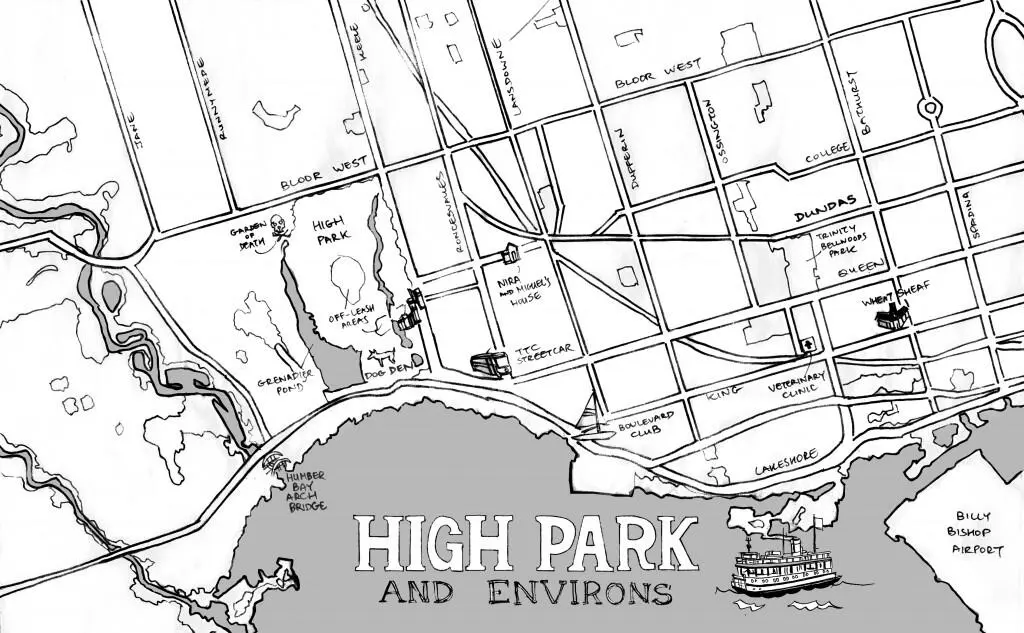

One evening in Toronto, the gods Apollo and Hermes were at the Wheat Sheaf Tavern. Apollo had allowed his beard to grow until it reached his clavicle. Hermes, more fastidious, was clean-shaven, but his clothes were distinctly terrestrial: black jeans, a black leather jacket, a blue shirt.

They had been drinking, but it wasn’t the alcohol that intoxicated them. It was the worship their presence elicited. The Wheat Sheaf felt like a temple, and the gods were gratified. In the men’s washroom, Apollo allowed parts of himself to be touched by an older man in a business suit. This pleasure, more intense than any the man had known or would ever know again, cost him eight years of his life.

While at the tavern, the gods began a desultory conversation about the nature of humanity. For amusement, they spoke ancient Greek, and Apollo argued that, as creatures go, humans were neither better nor worse than any other, neither better nor worse than fleas or elephants, say. Humans, said Apollo, have no special merit, though they think themselves superior. Hermes took the opposing view, arguing that, for one thing, the human way of creating and using symbols, is more interesting than, say, the complex dancing done by bees.

— Human languages are too vague, said Apollo.

— That may be, said Hermes, but it makes humans more amusing. Just listen to these people. You’d swear they understood each other, though not one of them has any idea what their words actually mean to another. How can you resist such farce?

— I didn’t say they weren’t amusing, answered Apollo. But frogs and flies are amusing, too.

— If you’re going to compare humans to flies, we’ll get nowhere. And you know it.

In perfect though divinely accented English — that is, in an English that every patron at the tavern heard in his or her own accent — Apollo said

— Who’ll pay for our drinks?

— I will, said a poor student. Please, let me.

Apollo put a hand on the young man’s shoulder.

— My brother and I are grateful, he said. We’ve had five Sleemans each, so you’ll not know hunger or want for ten years.

The student knelt to kiss Apollo’s hand and, when the gods had gone, discovered hundreds of dollars in his pockets. In fact, for as long as he had the pants he was wearing that evening, he had more money in his pockets than he could spend, and it was ten years to the instant before their corduroy rotted to irrecoverable shreds.

Outside the tavern, the gods walked west along King Street.

— I wonder, said Hermes, what it would be like if animals had human intelligence.

— I wonder if they’d be as unhappy as humans, Apollo answered.

— Some humans are unhappy; others aren’t. Their intelligence is a difficult gift.

— I’ll wager a year’s servitude, said Apollo, that animals — any animal you choose — would be even more unhappy than humans are, if they had human intelligence.

— An earth year? I’ll take that bet, said Hermes, but on condition that if, at the end of its life, even one of the creatures is happy, I win.

— But that’s a matter of chance, said Apollo. The best lives sometimes end badly and the worst sometimes end well.

— True, said Hermes, but you can’t know what a life has been until it is over.

— Are we speaking of happy beings or happy lives? No, never mind. Either way, I accept your terms. Human intelligence is not a gift. It’s an occasionally useful plague. What animals do you choose?

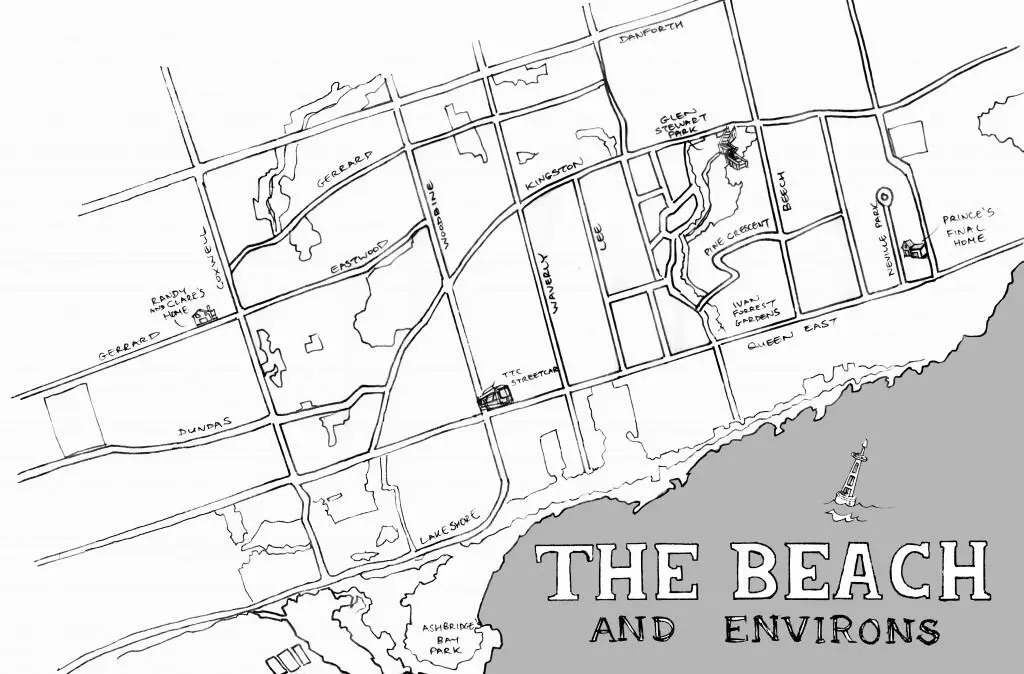

As it happened, the gods were not far from the veterinary clinic at Shaw. Entering the place unseen and imperceptible, they found dogs, mostly: pets left overnight by their owners for one reason or another. So, dogs it was.

— Shall I leave them their memories? asked Apollo.

— Yes, said Hermes.

With that, the god of light granted ‘human intelligence’ to the fifteen dogs who were in the kennel at the back of the clinic.

+

Somewhere around midnight, Rosie, a German shepherd, stopped as she was licking her vagina and wondered how long she would be in the place she found herself. She then wondered what had happened to the last litter she’d whelped. It suddenly seemed grossly unfair that one should go through the trouble of having pups only to lose track of them.

She got up to have a drink of water and to sniff at the hard pellets that had been left for her to eat. Nosing the food around in its shallow bowl, she was perplexed to discover that the bowl was not dark in the usual way but had, rather, a strange hue. The bowl was astonishing. It was only a kind of bubble-gum pink, but as Rosie had never seen the colour before, it looked beautiful. To her dying day, no colour ever surpassed it.

In the cell beside Rosie’s, a grey Neapolitan mastiff named Atticus was dreaming of a wide field, which, to his delight, was overrun by small, furry animals, thousands of them — rats, cats, rabbits and squirrels — moving across the grass like the hem of a dress being pulled away, just out of his reach. This was Atticus’s favourite dream, a recurring joy that always ended with him happily bringing a struggling creature back to his beloved master. His master would take the thing, strike it against a rock, then move his hand along Atticus’s back and speak his name. Always, the dream always ended this way. But not this night. This night, as Atticus bit down at the neck of one of the creatures, it occurred to him that the creature must feel pain. That thought — vivid and unprecedented — woke him from sleep.

All around the kennel, dogs woke from sleep, startled by strange dreams or suddenly aware of some indefinable change in their environment. Those who had not been sleeping — it is always difficult to sleep away from home — got up and moved to the doors of their cells to see who had entered, so human did this silence feel. At first, each of them assumed that his or her newfound vision was unique. Only gradually did it become clear that all of them shared the strange world they were now living in.

A black poodle named Majnoun barked softly. He stood still, as if contemplating Rosie, who was in the cage facing his. As it happened, however, Majnoun was thinking about the lock on Rosie’s cage: an elongated loop fixed to a sliding bolt. The long loop lay between two pieces of metal, effectively keeping the bolt in place and locking the cage door. It was simple, elegant and effective. And yet, to unlock the cage, all one had to do was lift the loop and push the bolt back. Standing on his hind legs and pushing a paw out of his cage, Majnoun did just that. It took him a number of attempts and it was awkward, but after a little while his cage was unlocked and he pushed the door open.

Читать дальше