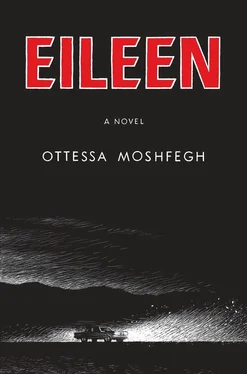

Had that Tuesday at work been a typical Tuesday, I would have spent it idle at my desk, watching the clock, sketching out my escape from X-ville for the hundredth time. If I left the Dodge at a filling station in Rutland — at a gas pump even — and just walked away, my head covered with a scarf, and simply boarded the next train to New York from Rutland station without anyone noticing me, people in X-ville might suspect I’d been kidnapped by some modern-day highwayman, expect to find me headless somewhere across the country, dumped by the side of the road or in some gruesome cheap motel scene. “Poor Eileen,” my dad would sniffle. I imagined. I dreamed. But that Tuesday I wasn’t thinking of any of those things. Instead, I thought of Rebecca, whose arrival at Moorehead seemed like a sweet promise from God that my situation could improve. I was no longer alone. Finally, here was a friend I could admire and open up to, who could understand me, my plight, and help me rise above it. She was my ticket to a new life. And she was so clever and beautiful, I thought, the embodiment of all my fantasies for myself. I knew I couldn’t be her, but I could be with her, and that was enough to thrill me. When she arrived that Tuesday, bustling in from the frigid morning snowdrifts, she whirled off her coat as though in slow motion — this is how I remember it — and shook it like a bullfighter as she strode up the corridor toward me, hair rippling behind her, eyes like daggers shooting down straight through my heart to my guts. She was pure magic. Her coat was a crimson wool swing coat with a gray fur collar. It was the same kind of fur I’d seen on the magazine cover. I stood up nervously when she got closer, expectantly, as though I were her assistant, her secretary, her maidservant. She nodded politely to the old ladies in the office and caught my eye on her way back to the locker room, which is where I followed her.

I had dressed for the occasion. From my mother’s wardrobe I’d composed an ensemble I thought made me look more cosmopolitan — navy blue, of course. I even wore an old fake pearl necklace. I’d brushed my hair and applied my lipstick more carefully that morning, dabbing at the edges of my mouth with the pressed powder so it stayed in place. I remember this because, as I’ve said, I was obsessed with my looks. Ironically, despite my preoccupation, my appearance on most days was slovenly, offensive even. “Disgraceful,” said my father. I thought, though, that I looked much better that morning. “Fancy” was probably the word I would have used. In any case, I followed the sound of Rebecca’s delicate heels ticktocking across the linoleum floor, and in the locker room she turned to me, saying, “Can you help me open my locker again? I can’t seem to do it.” She held up her long hands and twiddled her fingers in her skin-tight dove-gray leather gloves. “All thumbs,” she said. This helplessness was some kind of flirtation, I think, a manipulation of roles to keep me at her service, though I couldn’t have understood that at the time. I was perfectly pleased to spin the dial with finesse, blushing as though my talent for opening a locker was a sign of great virtue.

“But how do you know my combination?” she asked.

The locker opened with a sharp clank. I stepped back with pride.

“All the combinations are the same,” I told her. “But don’t tell the old ladies. They’d all have strokes.”

“You’re funny,” said Rebecca, wrinkling her nose. She carried her briefcase and a small leather purse from which she transferred her cigarettes into the pocket of her sweater. Her sweater looked so soft — it must have been angora, cashmere — it seemed to float around her like cotton candy. That day, just the second time I’d seen her, she wore all different shades of purple — lavender, violet, mauve. If she’d been any other woman, I would have discounted her as a hussy since her dress was so formfitting, so elegant, completely inappropriate for work in a prison. This wasn’t some romantic evening, after all. But Rebecca was no hussy. She was divine. I gazed at the elegant bend in her arm as she hung her coat up in her locker.

“I know it’s wrong to wear fur,” she said, seeing me stare. “But I can’t help myself. Chinchilla.” She petted the collar of her coat inside the locker as though it were a cat.

“No, no,” I said. “I was just admiring your cigarette case.”

“Oh, thanks,” she said. “It was a gift. See, it has my initials.” She pulled it out from her pocket and showed me. It was a striated silver cigarette case, the size of a pack of cards. I wanted to ask, “A gift from whom?” but held my tongue. She opened it and offered me a cigarette. They were Pall Malls, thick and filterless and the harshest cigarettes I’ve ever smoked. I was on them for several years later in life, always rather moved by the unexpected beauty of the motto written across their logo — a shield between two lions— Per aspera ad astra . Through the thorns to the stars. That described my plight to a tee, I thought back then, though of course it didn’t. Rebecca lit my cigarette with a flourish of the wrist. That thrilled me. When she lit her own, she tilted her head like a thoughtful bird, sucking in her cheeks just slightly. I remember all this with precise acuity. I was infatuated with her, clearly. And I felt in a way that just by knowing her, I was graduating out of my misery. I was making some progress.

“I don’t usually smoke,” I said, choking a bit, though I had a pack of Salems in my purse.

“Nasty habit,” Rebecca said, “but that’s why I like it. Not very becoming of a lady, though. It turns your teeth yellow. See?” And she leaned in toward me, a finger hooked on her bottom lip, stretching her gums apart to show me the inside of her mouth. “See the discoloration? That’s coffee and cigarettes. And red wine.” But her teeth were perfect — small, and white as paper. Her gums were pink and glossy, and the skin on her face was miraculously smooth, like a baby’s, flawless and radiant and light. You see women like this from time to time — beautiful as children, unscathed, wide-eyed. Her cheeks were full but firm, buoyant. Her lips were pale pink and bow-shaped, but chapped. By that slight imperfection I felt subtly disappointed, and yet redeemed.

“I don’t drink coffee,” I said, “so I guess I should have perfect teeth. But they’re all rotted due to my propensity for sweets.” This word, propensity, was not in my day-to-day vocabulary back then, and it was awkward to say it, and I worried Rebecca would see through my attempt to sound smart and laugh at me. But what she said next made my heart nearly burst in ecstasy.

“Well, I wouldn’t think to look at you!” She smiled wide, putting her hands on her hips. “You’re positively tiny! I admire that so much, how petite you are.” That was heaven. And then she went on. “I’m thin, too, of course, but tall and thin. Being tall has its advantages, but most men are just too short for me. Have you noticed, or am I imagining, men these days are getting shorter and shorter?” I nodded, rolling my eyes in solidarity although I couldn’t possibly answer her question. She put her purse in the locker and shut it. “They’re like little boys. Hard to find a real man, or at least a man that looks like one. To tell you the truth,” she began — I held my breath—“I’ve forgotten my locker combination. But I won’t trouble you again. You have better things to do, I’m sure. I have it written down in my desk. Now to find my way back to that office they gave me yesterday. I won’t ask for help with that either. I should be able to follow my nose. The smell of ancient leather.” She paused. “There’s that old couch in Bradley’s office next door to mine, you know, the fainting couch. How Freudian,” she said, widening her eyes sarcastically. “How outdated, I mean.”

Читать дальше