- - -

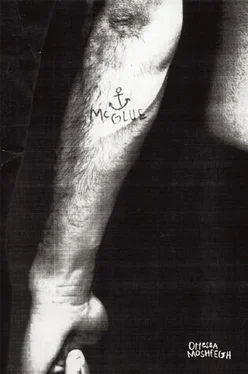

If I fell in love with McGlue I would want to mother him, and that is unhealthy for both of us. He needs another mother like he needs another hole in the head. I’d certainly want him to cut back a lot on his drinking, and trick-turning, and take better care of himself in general — bathing and sleeping — but I also know that a significant portion of his massive charm, a golden tooth winking in the jaw of a skull, lies in the drastically poor choices he makes, choices poorer and poorer, led down the paths he’s led down, and the severity of his cruelty to himself and others, and the tragedies of his actions — the swiftness with which he follows his own soul down into the various drinks available to him, sea and blood and grog, mead, gin, wine. With where he came from — dirt — and where he’s headed — phantasmagoric hell — you’d think he’d find room for some redeeming faith in love or God or state. But not McGlue.

He does like to read, when he can get his hands on a text, and so do I, and that’s what keeps us together.

Shortly after I did fall, irrevocably, in love with McGlue, because he’s the kind of queer, socially maladjusted bad-boy who can always float my boat — if not his own — Rivka Galchen did too. It’s not every day that a publisher launches a book prize. The publisher has to cross her legs and hope that she, the judge she’s picked, will settle on something she, the publisher, can love. Rivka says: “A sextant of the psyche, McGlue works its grand knowing through the mouthfeel of language; it’s a sharply intelligent, beautiful, and singular novel. A scion of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Raymond Carver at once, Moshfegh transforms a poison into an intoxicant.”

Hawthorne is the salty courtroom and the bitter docks; Carver is the raw taciturnity and long-suffered loves, maternal and filial and consensual. The poison is drink, a non-literary addiction; the poison is poverty and other harsh, historically accurate conditions that make a boy reckless with those who might love him, with his mortal body and his eternal soul, that turn his soft heart into a sharp or dull knife, one that cuts both ways. The intoxicant is writing this brilliant.

Rebecca Wolff

Founder and Editor, Fence Books

I wake up.

My shirtfront is stiff and bibbed brown. I take it to be dried blood and I’m a dead man. The ocean air persuades me to doubt, to reel my head in double, triple takes towards my feet. My feet are on the ground. It may be that I fell face first in mud. Anyway, I’m still too drunk to care.

“McGlue!”

A wrathful voice calls out from the direction of sunshine, ship sails hoisting, squeaks of wood and knots, tight. I feel my belly buckle. My head. Just last spring I cracked it jumping from a train of cars — this I remember. I get back down on my knees.

Again, “McGlue!”

This McGlue. It sounds familiar.

A hand grips my shirt and pokes at my back, steers me to the plank and I get on, walking somehow. The ship is leaving. I puke and hold on to the side of the stern and belch bile for a bit watching the water rush past, until land is out of sight. It’s peaceful for a small while after. Then something inside me feels like dying. I turn my head and cough. Two teeth skip from my mouth and scatter across the deck like dice.

Eventually I am put to bed down under. I fish around my pockets for a bottle and find one.

“McGlue,” says the cabin boy, the sissy, “hand that shit over here.”

I swig it back. Some spills down my neck and wets my soiled collar. I let the empty bottle fall to the floor.

“You’re bleeding,” says the fag.

“So I am,” I say, pulling my hand away from my throat. It’s dark, rummy blood, I taste it. Must be mine, I think. I think of what use it may have if I get thirsty later. Fag looks worried. I don’t mind that he unbuttons my shirt, don’t even beat his hands away as he steers my neck one way, then the other. Too tired. Inspection time. He says he finds no holes in me to speak of. “Ah ha,” I tell him. Fag’s face has a weird sneer, and he looks a little scared and hovers there over me, red hair tucked carefully into a wool cap, a dot of sweat sitting in the trivet of his upper lip just below his little nose. He looks me in the eye, I’d say, with some fear.

“No touch,” I say, ruffling the blanket back up. It’s a grey-and-red striped blanket that smells of lambs’ milk. I hold it over my face while Fag goes about. It’s good here under the blanket. My breath shows in the dark. So dark I could almost sleep.

My mind travels the cold hills of Peru where I got lost one night. A fat woman fed me milk from her tit and I rode a shaggy dog back down along a river to the coast. Johnson was there with the captain, waiting. That was trouble. Hit warm with the rum now I close my eyes.

“What have you done?” says the captain next time I open them. The blanket is stripped away like a whip. Saunders removes my shoes. I hear the boat creak. Someone walks down the hall ringing a bell for supper. The captain stands there by the cot. “We want to hear you say it,” says the captain. I feel sick and tired. I fall asleep again.

They are moving mouths. Saunders and the fag stand by the door. Fag holds a bottle, Saunders dangles keys.

“Gimme.” My voice breaks. I can breathe, hear. He passes the bottle over.

“You killed Johnson,” says Saunders.

I get a good half the bottle down and steady my neck, fold my shoulders back. I feel my jaw let go, look down, remembering blood. My shirt is gone.

“Where’s my shirt.”

“Did you really do it?” says the fag. “Officer Pratt says he saw you. Drunk at the pub in Stone Town. Then run away to the dock just before they found him in the alley.”

“Trash, it’s cold. All possessed till takers of this anti-fogmatico, thank you, faggot,” I say. Drink.

“They found him stabbed in the heart dead, man,” says Saunders, gripping the keys, eyebrows smarting.

“Who has a brick in a hat, Saunders? Quit it, now. It’s keeping me all-overish. Is there food?” The fag takes the empty bottle from where I lay it on the blanket. I feel like dreaming. “Where’s your freckles, Puck? Let’s trade places.”

They aren’t talking to me anymore.

“Food, man. Shit.” I’m completely awake now. In one glance I take in the room: placards, grey-painted wood walls, wire hooks, some hung-up duck and Guernsey frocks, a grey, shield-shaped mirror. Sunlight hazes in, block-style, speckled with white dust. The shadows of men on deck pass along the walls through the small rectangular windows up high above my cot. An empty cot on either side of me. A whine and creak of ship and ocean. I yearn for ale and a song. This is home — me down in the heart of the drifting vessel, wanting, going somewhere.

Saunders and Fag pass words and go out and I hear Saunders lock the door and I protest with, “Come back and smile, Saunders. Give me the goods, what’s up?” and nothing happens.

It’s not the first time I’ve been in the hole on this trip. Will be made to work the pump well each morning and darn sails like an old maid once I’m well again. I think of my mother as I imagine her always at the loom through the nailed-down windows of the mill, me a wee tip-toed kid, fingers hoisting my eyes barely above the horizon of the window ledge, watching my stoop-backed, prim, high-nosed mom at work, and watching her again that night at the table in our little house, calling me and brother “good boys,” pushing crumbs, counting coins and coughing, my sisters in bed already, my mother’s pale, tuckered out hair splayed across her back. All the stars outside just sitting there. The cold rinse of Salem night after running hot all day. I’d throw a rock at a window if I could, if I had one. Did Saunders say Johnson was in unkeeps? I’ll get up and see about it.

Читать дальше