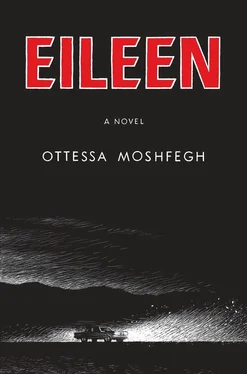

As I did oftentimes when I was disturbed, I headed back up to Randy’s. On the drive I thought of his thick arms, his top lip, sensuous yet boyish, the sideways glint of his smile which he tried to hide behind a comic book or some funny magazine. Would he miss me when I was gone? Perhaps he would. “Oh, Eileen,” he’d say to the cops when they’d investigate my disappearance. “She left before I ever got the nerve to ask her on a date. I missed out and I’ll always regret it.” It soothed me to think of us together, perhaps reunited after several years which I’d have spent becoming a real woman, his type — whatever that meant — and we’d embrace each other and cry at the sadness of our lost love and separation. “I was so blind,” Randy would say, kissing my fingers, tears coasting down his beautiful cheekbones. I loved a crying man — a weakness which led me into countless affairs with whiners and depressives. I suspected Randy cried rarely, but when he did, it was a thing of great beauty. Did I really drive by his apartment that afternoon, my seat wet with melting snow? Of course I did. I can’t say what I was looking for exactly, though I was ever hopeful that he might come out and profess his love, save me, run away with me, solve all my problems. As I idled in front of his place, I was suddenly overcome with nausea. I opened the car door and vomited. The gray, melted ice cream sank into the snowbank, then disappeared.

As soon as I got home that afternoon, I ran upstairs to my mother’s room and peeled off my cold, wet pants and underwear. My father, sitting on the toilet across the dim hall, swung the bathroom door open to ask, “Where’ve you been?”

I pulled on a pair of old woolen tights and went and found a spare bottle of gin I’d hidden in the closet and handed it to my father. He took it and flipped the light on with his free hand. When his newspaper slipped from his knees, I caught sight of the dark patch of pubic hair in his lap. That terrified me. I saw, too, his gun sitting on the edge of the sink. I’d wondered about that gun from time to time. In my darkest moments, I’d imagined easing it out from under my father’s sleeping body and pulling the trigger. I’d aim straight through the back of my skull so that I’d slump down over him, my blood and brains oozing all over his cold, flaccid chest. But honestly, even in those darkest moments, the idea of anyone examining my naked corpse was enough to keep me alive. I was that ashamed of my body. It also concerned me that my demise would have no great impact, that I could blow my head off and people would say, “That’s all right. Let’s get something to eat.”

That night I lay on my cot and poked at my belly, counted my ribs with gloved fingers. It was cold up in the attic, and that cot was flimsy. It just barely bore my weight: one hundred pounds with clothes on, if that. If I used too many blankets, the joints of the cot would wiggle, and with every breath the frame would rock and sway like a boat in the tide and I couldn’t sleep. I could have found a wrench to tighten up the bolts and screws or whatnot, but like with the car’s broken exhaust pipe, I couldn’t be bothered to deal with fixing things. I preferred to wallow in the problem, dream of better days. The attic reminded me of where a visiting uncle would sleep, if I’d had one. A good uncle, maybe an army man, inclined to build things, fix things, who never complained of cold or thirst, who would eat the worst cut of beef or chicken full of fat and gristle without a second thought. I imagined his earlobes would be long and flabby and his shoulders small, but his body muscled, eyes wide. Perhaps that good uncle was my real father, I fantasized. I sometimes scanned my mother’s wardrobe for evidence of adultery. The discovery of food stains, coffee drippings down the front of a cotton blouse, or lipstick smeared on a yellowed collar was not exactly like hearing a voice from the grave, but I guess I hoped to find something useful. A hint, a greeting, proof that she’d loved me, anything. I don’t know. I don’t know why I wore her clothes the way I did, for years after she died. I let my dad assume it was some sort of reluctance to part with the dead woman, an old dress like a badge of loyalty, carrying on my mother’s spirit, whatever nonsense. But I think I really wore her clothes to mask myself, as though if I walked around in such a costume, nobody would really see me.

I remember sitting up on my cot under a bare lightbulb and surveying the attic. It’s a charming picture of misery. There were loose drawers from a dresser stacked full of moth-eaten linens that had belonged to my mother’s mother. There were boxes of old books and papers, an old phonograph and several crates of records that I had never tried to play. The sloping ceiling forced me to duck and then crawl toward the window facing the backyard, where not much could be distinguished apart from the white snow and a few bare, black tree branches, everything lit up violet under the dwindling afternoon sky. Somewhere buried down there was Mona, my dead dog. I thought of my mother when she lay sick in bed, her hands in a pile of mis-knitted afghan, complaining to my father at the top of her lungs that were there a God in this world, He was a bastard. “I should be dead, already,” she insisted. I dutifully boiled the chicken soup on the stove, day in, day out, and brought her the clear broth in a green salad bowl big enough to catch the spills during the struggle of having to feed the woman spoon by spoon, her arms flailing weakly and haphazardly in resistance.

One day I went out back to hang the laundry and found the dog belly-up in the uncut grass, tall and dried and dead in the bleaching sun. Perhaps God took the wrong soul, I thought in a freak moment of sentimentality, and I cried quietly, back pressed up against the house. I left the wet laundry in the basket, but draped a sopping pillowcase over Mona’s body. It took a day for me to muster the courage to go back out there. By then the laundry had congealed and dried, and the sight of the dead dog when I lifted the pillowcase made me gag and spill the contents of my stomach — chicken, vermouth — into the dry dirt. It took me several hours to dig a sufficient hole with a trowel, push Mona in with my foot — I couldn’t bring myself to touch her with my hands — and cover the body with the brittle earth. A week later, when my father kicked over the dog’s dish of stale and smelly kibble, he simply said, “Damn dog,” and so I threw the whole thing out, and told no one. A few days later my mother was dead, and I let the tears flow openly at last. It’s a romantic story and it may not be accurate at this point since I’ve gone over it again and again for years whenever I’ve felt it necessary or useful to cry.

Looking out over the icy backyard that night, I cried again for my dog, sorry that she would have to stay there in X-ville for all of eternity. I considered digging up her bones so I could take her with me. I really considered putting on my ski pants, a heavy wool sweater, snow boots, mittens, the tight knit cap, and going out there with a shovel. I hadn’t marked the grave with anything, but I felt that Mona would call to me, that I would intuitively know where to break ground. Of course I didn’t even try. I’d have needed some kind of pickax, the kind they use in graveyards. Imagine the labor necessary to bury a whole person without a machine to do the digging. It’s not like in the movies. It’s not that easy. How did they bury people in the winter in the old days, I wondered. Did they leave the bodies out to freeze until the spring? If they did do that, they must have kept them somewhere safe, in the basement perhaps, to lie in silence in the dark and cold until the thaw.

Читать дальше