I followed along behind. The crowd had gone silent now, and it seemed that everyone had decided to watch us descend the stairs. I held my head up and tried to look like I didn’t notice. When I reached the ground, I said thanks to the four men, and took over Abbott’s wheelchair, and pushed him quickly through the gate. As I myself exited the grandstand, I glanced back and saw that the fourth heat of the derby had begun, and the crowd had gotten itself attentive and noisy all over again. Even Billy Ansel. Life goes on, I might have said, if there had been anyone to hear me. Nichole Burnell I could not see from there.

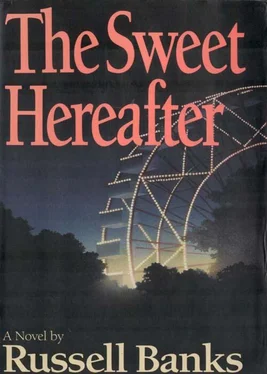

The sky was a pale sheet of light sent up from the fairgrounds, but the field was dark as we crossed it toward the parking lot, passing the hulks of wrecked cars, idling pickups, and tow trucks. The grass was wet with dew. Except for a couple of drivers seated or snoozing in their vehicles, everyone was over by the stage and the railing, watching the derby, and the sound of the cars as they roared back and forth and collided with one another was dulled and dimmed, softened, like background noises in a bad dream. Over by the midway, the Ferris wheel spun slowly, rising and falling in the distance like a gigantic clock. The faint music of the merry-go-round mingling with the gravel-voiced calls and come-ons of the midway barkers was strangely sad to me; it was like the sound of childhood — mine, Nichole’s, everyone’s. Even Abbott’s. Our childhoods that were gone forever but still calling mournfully back to us.

There’s not much more to tell. I got Abbott to the van, situated him by the side door and lowered the lift for him, raised him up and locked the wheelchair into place next to the driver’s seat. Then I came around and got in myself and started driving. We departed quickly from the parking lot, which was pretty much filled, with no more cars arriving this late and no one but us leaving this early, and soon we were on the road, headed home.

When the fairgrounds and all its illumination were sufficiently behind us, the sky darkened nicely, and the stars seemed to come out all at once, a wide swath of them spreading like sparkling seeds overhead. It was a clear night, fresh and cool, and I knew that autumn was going to come on fast now, the way it does up here.

Over to my left, the East Branch of the Ausable ran through the darkness, and a dark spruce woods hove up on my right. At the edge of the road, low and close to the ground, first on one side, and then on the other, I began to see the eyes of animals suddenly flash and glitter as I passed along the way, reflecting my headlights back at me and then as quickly flaring out. For a brief second, though, their eyes were pure white and flat, like dry, coldly glowing disks, and it was as if the animals had all come to the edge of the forest, and there by the side of the road they had waited and watched for me, until I had passed them by and the safe familiar darkness had returned.