“Would you like to go to the fair this year, Nichole?” Daddy asked. He had slowed the car and had been looking at the fairgrounds with me, probably thinking some of the same thoughts.

“When is it? When does it start?”

“Starts tomorrow, runs all week, right through the weekend.”

“I don’t know, Daddy. Maybe, though. Let me think about it, okay?”

He said sure, and we drove on into town.

We had one more conversation before we got home, which I think was responsible somehow for my deciding to go to the fair, although it’s not really connected. As we pulled into the yard, I said to Daddy, “Nothing will happen to Dolores, will it?”

He shut off the engine, and we sat there for a moment in silence, listening to the dashboard clock tick. Finally, he said, “No. Nobody wants to sue Dolores. She’s one of us.”

“Will the police do anything to her now?”

“It’s too late for that. Dolores can’t drive the school bus anymore, anyhow; the school board saw to that right off. I doubt she even wants to. Everyone knows she’s suffered plenty.”

“But everyone will blame her now, won’t they?”

“Most will, yes. Those that don’t know the truth will blame Dolores. People have got to have somebody to blame, Nichole.”

“But we know the truth,” I said. “Don’t we?”

“Yes,” he said, and for the first time since before the accident, he looked me straight in the face. “We know the truth, Nichole. You and I.” His large blue eyes had filled with sorrowful tears, and his whole face seemed to beg for forgiveness.

I made a small thin smile for him, but he couldn’t smile back. Suddenly, I saw that he would never be able to smile again. Never. And then I realized that I had finally gotten exactly what I had wanted.

“Well,” I said, “it’s over now.”

He turned away from me and got out of the car, and when he came around to my side with the wheelchair and opened my door, I said to him, “Daddy, I think I do want to go to the fair.”

He concentrated on unfolding the chair and said nothing.

“Let’s go Sunday afternoon and see everything,” I said. “The last day is always the best. Everyone in town goes then, and we can sit in the grandstand, and everyone will see us together. We can look at the livestock too, and the rides, the midway, the games, everything. All of us together, the whole family.”

He nodded somberly and lifted me out of the car and set me into my wheelchair. Then he pushed me up the ramp and into the house.

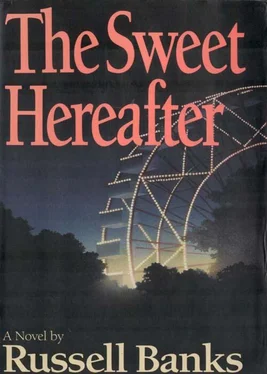

Every August since we were married, and before that, separately, since childhood, Abbott and I have attended the Sam Dent County Fair, which by rights should be held over in Marlowe, since that’s the county seat. Instead, it’s held here in Sam Dent, where there is a fine old fairgrounds out along the East Branch of the Ausable River. Abbott loves the fair, especially the demolition derby; weeks in advance, he gets himself worked up to a fever pitch, practically, almost like a child.

Except for the pleasure I get from his excitement, I myself can take the fair or leave it, it’s just one of the stops that a person makes in the course of a year, but I do confess to enjoying the livestock exhibitions. I like to wander through the dairy barns more than any of the other exhibits, probably because of my childhood experiences, what with my father having been a dairy farmer. The dim warm stalls and the smell of wood chips and hay and fresh cow manure, the slow and gentle movements of cattle and their large moist eyes — those things cut straight through all my troubles to my heart and bring me practically to tears as I pass along the long low barns and stop here and there to admire and maybe even speak to an especially fine Jersey or a pretty black and white Holstein, which is the type of cow my father raised.

It’s not the same for Abbott. He’s more at ease in the flash and bustle and noise of the midway and, as I said, the demolition derby, which he prefers to watch from high in the grandstand. “You … need … perspective … to … experience … it,” he explains. That’s a problem, of course, with his being confined to a wheelchair in recent years. Normally, what happens is that a couple of men from town spot us before we even get to the grandstand and meet us at the bottom of the steps and, one on each side, latch on and carry Abbott in his wheelchair to the top level, where he can set his brake and watch the whole thing to his heart’s delight, to the very end. Afterwards, usually the same fellows from town show up and carry him back down to the ground, where I take over and wheel him to the parking lot.

This year, though, things were different. I probably should have expected it, but it caught me by surprise. Although I don’t think it surprised Abbott one bit — there’s very little surprises that man. But without having said anything to him, without our actually discussing it, I figured that enough time had passed for people to have gone through their first tangled reactions to the accident and come out on the other side, just as I more or less had myself; I had pretty well stayed out of sight and, I hoped, mind, all these lonesome months, which was only proper; by now, I thought, people would have put their dark conflicted feelings about me behind them and would once again be free to act toward me and Abbott like the dear friends and neighbors they had always been. Sam Dent was our permanent lifelong community. We belonged to this town, we always had, and they to us; nothing could change that, I thought. It was like a true family. Certainly, terrible things happen in every family, death and disease, divorce and blood feuds, just as they had in my own; but those things always have an end to them and they pass away, and the family endures, just as ours had. The same must hold for a town, I thought. But I’m a sanguine person, as Abbott says. Too sanguine, I guess.

It was early Sunday evening when we got there, the last day of the fair, and I had to park the van at the farthest end of the parking lot, a long bumpy haul from the grandstand. There had been a thunderstorm earlier, one of those late August storms that move quickly and heavily through the mountains like a freight train from Canada, and we had waited at home for it to pass over into Vermont, which it did around six o’clock, leaving the sky cloudless and tinted a stony shade of blue and the air moist and scrubbed and cool. For the first time that summer, you could smell fall coming on.

Because of the storm, though, we were late and didn’t have time to visit the livestock barns, which grieved me some, or linger along the midway like Abbott enjoys. They start the demolition derby right at sundown, for it is definitely more exciting to sit up high in the old wooden stands and watch the cars down below smash against each other under spotlights than to do it in broad daylight, when the whole event might seem a foolish thing for a normal person to view. At least I would find it somewhat embarrassing in daylight, although I doubt that would matter much to Abbott. He’s not as self-conscious as most people, due to his stroke, no doubt, and what he’s learned from it.

From the parking lot, we made our way through the gate and along the far side of the field in front of the grandstand, which wasn’t easy, as the lane was rutted and wet, the grass trampled by the crowds of the last week. We were cheerful, though, Abbott and I; it was our first time out in public together since last winter. After the accident, I had attended the funerals, but alone, without even Abbott to accompany me; it was a way of bearing witness, I guess you could call it. I kept to myself, spoke to no one, and left immediately after the services. It was just something I had to do, something crucial between me and the children. I don’t think people, the adults, quite wanted me there among them, which was understandable, but I had to do it — for the children, who, if they could have spoken for themselves, would surely have asked me to attend their funerals and say a prayer for each of their dear departed souls. And I did. They would have thought me cowardly if I had stayed home instead.

Читать дальше