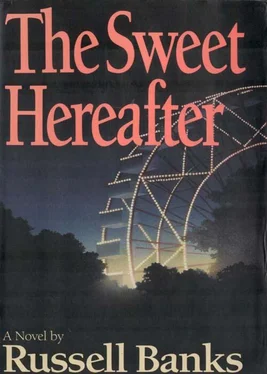

Russell Banks

The Sweet Hereafter

By homely gift and hindered Words

The human heart is told

Of Nothing—

“Nothing” is the force

That renovates the World—

Emily Dickinson (#1563)

A dog — it was a dog I saw for certain. Or thought I saw. It was snowing pretty hard by then, and you can see things in the snow that aren’t there, or aren’t exactly there, but you also can’t see some of the things that are there, so that by God when you do see something, you react anyhow, erring on the distaff side, if you get my drift. That’s my training as a driver, but it’s also my temperament as a mother of two grown sons and wife to an invalid, and that way when I’m wrong at least I’m wrong on the side of the angels.

It was like the ghost of a dog I saw, a reddish-brown blur, much smaller than a deer — which is what you’d expect to see out there that early — although the same gingerbread color as a deer it was, moving fast behind the cloud of snow falling between us, then slow, and then stopped altogether in the middle of the road, like it was trying to make up its mind whether to go on or go back.

I couldn’t see it clearly, so can’t say what it was for sure, but I saw the blur clearly, that’s what I mean to say, and that’s what I reacted to. These things have to happen faster than you can think about them, because if they don’t, you’re going to be locked in place just like that dog or deer or whatever the hell it was, and you’ll get smacked head-on the same as that dog would have if I hadn’t hit the brake and pulled the wheel without thinking.

But there’s no point now to lingering over the dog, whether it was a dog or a tiny deer, or even an optical illusion, which, to be absolutely truthful, now seems likeliest. All that matters is that I saw something I didn’t expect out there and didn’t particularly identify at the time, there being no time for that — so let’s just say it was like a dog, one of those small red spaniels, smaller than a setter, the size of a kid in a rust-colored snowsuit, and I did what anyone with half a brain would have done: I tried to avoid hitting it.

It was in first light and, as I said, blowing snow by then, but when I started my route that morning, when I left the house, it was still dark, of course, and no snow falling. You could sniff the air, though, and smell it coming, but despite that, I had thought at first that it was too cold to snow. Which is what I said to Abbott, who is my husband and doesn’t get out of the house very much because of his being in a wheelchair, so I have this habit of reporting the weather to him, more or less, every morning when I first step out of the kitchen onto the back porch.

“I smell snow,” I said, and leaned down and checked the thermometer by the door. It’s posted low on the frame of the storm door, so Abbott can scoot over and open the inside door and check the temperature anytime he wants. “Seventeen below,” I told him. “Too cold to snow.”

Abbott was at one time an excellent carpenter, but in 1984 he had a stroke, and although he has recovered somewhat, he’s still pretty much housebound and has trouble talking normally and according to some people is incomprehensible, yet I myself understand him perfectly. No doubt it’s because I know that his mind is clear. The way Abbott has handled the consequences of his stroke is sufficient evidence that he is a very courageous man, but he was always a logical person with a lively interest in the world around him, so I make an effort to bring him as much information about the world as I can. It’s the least I can do.

“Never … that … cold,” he said. He’s worked out a way of talking with just the left side of his mouth, but he stammers some and spits a bit and makes a grimace that some people would find embarrassing and so would look away and as a result not fully understand him. I myself find his way of talking very interesting, actually, and even charming. And not just because I’m used to it. To tell the truth, I don’t think I’ll ever get used to it, which is why it’s so interesting and attractive to me. Me, I’m a talker, and consequently like a lot of talkers tend to say things I don’t mean. But Abbott, more than anyone else I know, has to make his words count, almost like a poet, and because he’s passed so close to death he has a clarity about life that most of us can’t even imagine.

“North … Pole’s … under … snow,” he said.

No arguing with that. I grabbed my coffee thermos, pecked him with a kiss and waved him goodbye as usual, shut the door and went out to the barn and got my bus started. I kept an extra battery and jumper cables in the kitchen, just in case, but the old girl was fine that morning and cranked right up. By nature I’m a careful person and not overly optimistic, especially when it comes to machinery and tools; I keep everything in tiptop condition, with plenty of backup. Batteries, tires, oil, antifreeze, the whole bit. I treated that bus like it was my own, maybe even better, for obvious reasons, but also because that’s my temperament. I’m the kind of person who always follows the manual. No shortcuts.

Weather, meaning snow or ice, stopped me numerous times a year — of course, those were days that Gary Dillinger, the principal, called school off anyhow, so it didn’t count — but in twenty-two years I did not miss a single morning or afternoon pickup because of a mechanical breakdown, and although I went through three buses in that time, it was only to have each bus replaced with a larger one, as the town grew. I started back in 1968, as a courtesy and convenience, with my own brand-new Dodge station wagon, carting my two boys, who were then in Sam Dent School, and scooping up with them the six or eight other children who lived on the Bartlett Hill Road side of town. Then the district made my route official, enlarging it somewhat, and gave me a salary and purchased me a GMC that had twenty-four seats. Finally, in 1987, to handle the baby boomers’ babies, I’d guess you’d call them, the district had to get me the International fifty-seater. My old Dodge wagon finally gave out at 168,000 miles, and I drove it behind the barn, drained it, and put it up on blocks, and now for my personal vehicle and for running Abbott over to Lake Placid for his therapy I drive an almost new Plymouth Voyager van. It’s got a lift for his chair, and he can lock the chair into the passenger’s side and sit next to me up front, which gives him a distinct pleasure. The old GMC they use for hauling the high school kids over to Placid.

Luckily, our barn being plenty large enough and standing empty, I was always able to park the bus at home overnight, where I could look after it in a proper way. Not that I didn’t trust Billy Ansel and his Vietnam vets at the Sunoco, where the district’s two other buses were kept and serviced, to take good care of my bus; I did — they are intelligent mechanics and thoughtful men, especially Billy himself, and anything more complicated than a tune-up I happily turned over to them. But when it came to daily maintenance, I was like the pilot of an airplane — no one was going to treat my vehicle as carefully as I did myself.

That morning was typical, as I said, and the bus started up instantly, even though it was minus seventeen out, and I took off from our place halfway up the hill to commence my day. The bus I had given the name Shoe to, which is just something I do, because the kids seemed to like it when they could personalize the thing. I think it made going to school a little more pleasurable for them, especially the younger children, some of whose home lives were not exactly sweetness and light, if you know what I mean.

Читать дальше