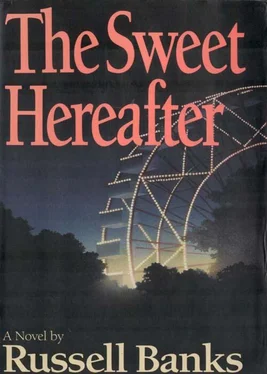

Russell Banks - The Sweet Hereafter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Sweet Hereafter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, Издательство: Little Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet Hereafter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet Hereafter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet Hereafter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet Hereafter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet Hereafter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I nodded my head yes, but Abbott didn’t even blink.

“What Nichole said she witnessed,” he said, “was the accident. She was sitting in the bus up front next to you, Dolores. I guess I was the only other witness, but I was driving a ways behind you, and not paying much attention, either. So what Nichole had to say counted a whole lot. Because they subpoenaed me, Mitchell Stephens did, and when they did that, I told him and the other lawyers that I frankly couldn’t say for sure how fast you were driving that bus that morning. When it went over. Which is the gospel truth. All I knew was the speed that I myself usually drive up there. Fifty-five to sixty, is what I told them. Nichole, though, she was very certain. She said she remembered it clearly — she knew how fast you were going when the bus went off the road. That’s what she told them.”

He paused and looked back down at the track, where the winner of the first heat had been determined: car number 43, a pink beetle-shaped Hudson with “Death to the APA” painted across the roof, “Tatum” on the hood, and “The Bone Rules” along the sides. That was the driver’s name for himself, I guess — The Bone. In reality, it was Richie Green, a good kid, not really a bone. Tatum is Tatum Atwater. Wreckers and pickups with winches were rapidly hauling the smoking carcasses of the losers off the track and onto the field, and a second group of sixteen cars was lining up to enter the arena.

“How fast did the child say I was going?” I asked him. To save Abbott the trouble, I suppose.

“Seventy-two miles an hour is what she told them.” He wouldn’t look at me when he said it, but he said it. I have to hand Billy that.

“She told them I was driving seventy-two miles an hour?”

“Yes. Dolores, I thought you knew.”

“How would I know?”

“No way, I guess. I just figured you knew, like everybody else. I’m sorry, Dolores,” he said.

“No, don’t be sorry to me, Billy. Not as long as you know the truth.”

“Well, yeah, I know the truth.”

“That’s two of us, then,” I said. There were three of us, of course, counting Nichole. Well, four, actually, counting Abbott. But Abbott knew the truth because he happened to believe me, and I only assumed that. Abbott hadn’t been there with me that January morning, out on the Marlowe road with the snow coming down and the sight of the mountains and the valley so lovely that when you see it your legs go all watery and you have to hold your breath or you’ll say something foolish, with the children all easy and at play in the school bus, and me in charge of picking them up on time at their homes scattered across the town and carrying them over those narrow winding roads for miles, until we came to the big road and began our descent to the school in the valley below. Abbott wasn’t with me then; I was alone.

Now, in addition to the truth, I knew what nearly everyone else in town knew and believed, and if they didn’t, they were learning and coming to believe it this very minute, probably, from the person standing or sitting next to them here at the fair — they were learning that Dolores Driscoll, the driver of the school bus, was to blame for the terrible Sam Dent school bus accident last January. They were learning that Dolores had been speeding, that she had been driving recklessly, driving the bus in a snowstorm at nearly twenty miles an hour over the limit, that Nichole Burnell, the beautiful teenaged girl who’d come out to the fair in her wheelchair, a child who herself had almost died in the accident, had sat next to the driver, that Nichole had seen how fast the vehicle was moving, that she had told it to a court. Dolores Driscoll was the reason why the bus had gone off the road and tumbled down the embankment and into the icy water-filled sandpit. Dolores Driscoll was the reason why the children of Sam Dent had died.

What did I feel then? I remember feeling relieved, but that’s a weak word for it. Right away, without thinking once about it, I felt as if a great weight that I had been lugging around for eight or nine months, since the day of the accident, had been lifted from me. A huge stone or an albatross or a yoke. One minute it was there, and because it had been there for so long, I had grown used to it; and the next minute it was gone, flown away, disappeared, and I was suddenly able to recognize what a terrible weight I had been carrying all these months. That’s strange, isn’t it? You’d expect me to feel angry, maybe, unjustly accused and all that. But I didn’t. Not at all. I felt relieved. And, therefore, grateful. Grateful to Billy Ansel, for revealing what Nichole had done, and grateful to Nichole for having done it.

And for once, possibly for the first time in our life together, I did not know what Abbott was thinking or feeling. Even more peculiar, I didn’t care, either. He might be angry, he might be resentful, he might even think I had lied to him. I didn’t care; it didn’t matter what Abbott thought. I felt myself singled out in a way that had not happened to me before, and although I have never experienced such a solitude as that, I have also never felt quite so strong.

I looked over at Abbott; he had no idea what I was feeling, and it actually pleased me that he didn’t.

As soon as Billy had ceased speaking, Abbott had swung his attention back to the derby. The second heat was now almost over. Billy was concentrating on his bottle, and when he wasn’t drinking, he appeared to be studying his feet. Stacey Gale was like Abbott, all caught up, apparently, in the smoke and the furious sound and sight of the cars smashing one another to bits.

I said nothing. I just sat there and contemplated my strange new feelings, letting them wash over me — relief, gratitude, aloneness — naming them to myself as they came, one hard upon the other, in a series, or a cycle would be a better word, for each wave of feeling seemed to be the direct and sole cause of the next. Down below, the single surviving car, a mangled old Impala with a front fender crumpled and dangling off it, was pronounced the winner, and the tow trucks rushed into the arena and hauled the losers off, and the cars in the third heat came roaring in.

Suddenly, Abbott raised his left arm, his good one, and pointed. I followed his finger down to the arena and saw what he saw, old Boomer, my Dodge station wagon. Number 57, it was. Jimbo Gagne had painted the car black and had written the number and his first name and a peace symbol across the hood in big yellow letters. Along the side was the name of the sponsor, not-quite-free advertising for Billy Ansel’s Sunoco station. And on the top of the wagon, in huge letters, he had painted the word boomer. I might not have recognized it otherwise. All the window glass was gone, of course, and the trim and hubcaps, and with no muffler it was blatting like the others, but I could identify its beat, and it sounded pretty good to me: Jimbo had not just got it running again, after it had sat dead on cinder blocks for years, but got it running smoothly. It looked good too — glossy black all over, with no chrome, no gaudy decorations; like a ghost car, it was dark and unadorned and all business. The car was positioned in the middle of the pack, not an advantageous spot in a demolition derby, but it was bigger than most of the others in the heat, and like Jimbo had said, it had a good power-to-weight ratio — plenty of both.

What happened then surprised me at the time but seems natural now. The flag was dropped, and the cars commenced to smash into one another, ramming each other from behind, the stronger cars quickly driving the weaker against the heavy steel railing in front of the stage and grandstand, shoving them sideways and backward through the mud, with wheels spinning and tires smoking and clods of dirt flying through the air. And every time Boomer got hit, no matter who hit it, the crowd roared with sheer pleasure. A car with the words “Forever Wild Development Corp.” painted over the hood slammed Boomer from the side, driving it into another car, the Cherokee Trail Condominium car, and everyone in the stands stood up and cheered. I could see Jimbo wrestling with the wheel, frantically trying to regain control, shoving the gearshift forward and back, rocking Boomer until it was freed from the Cherokee Trail car, when another car hit it from the front and sent it up against the rail, pinning it there, and everyone cheered happily to see it. But somehow, before the referees were able to slap it with one of their flags and pronounce it out, Jimbo got it moving again, and Boomer charged back into the pack in the middle. Seven or eight of the cars were dead by now, stalled, trapped against the rail or boxed in between two other dead cars and unable to move. But Boomer was still alive.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet Hereafter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet Hereafter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet Hereafter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.