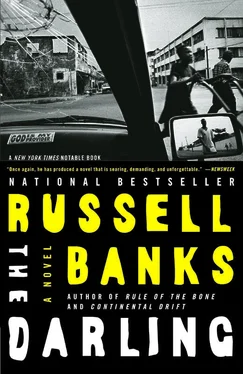

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Standing next to Woodrow and slightly behind him, yet making herself visible to the crowd, was a young woman with a thick, pouty upper lip. A naked baby was perched on her wide, outslung hip. The woman was very dark, almost plum colored, with glistening hair that was braided and coiled like a nest of black snakes and wore a bright yellow-and-white sash across her bare breasts. She stared at me unblinking. Everyone else seemed not even to notice my presence. Woodrow, too, ignored me. Or perhaps he just hasn’t noticed my arrival yet, I thought. Or maybe he didn’t notice my absence in the first place.

I flipped a small, discreet wave in his direction. Over here, Woodrow! He saw me. I know he saw the tall white woman standing at the edge of the crowd. How could he have missed me, for heaven’s sake? But he seemed to look right through my body, as if it were transparent, a pane of glass between him and his people.

I didn’t know what to do. I turned to my guide, the boy who had brought me here, and said, “What should I do?”

He smiled sweetly and shrugged.

“Do you speak English?”

He nodded yes and said, as if reciting from a textbook, “I learn it at missionary school. I go to missionary school.”

“Like Woodrow. Mr. Sundiata.”

“Yes.”

“What’s your name?”

“Albert,” he said. “I am Sundiata, too. Same like Woodrow. My father and Woodrow’s brother the same-same.”

“Should I go over there?” I asked. When I pointed towards Woodrow and the others on the dais, they were stepping down from the low platform and entering the hut, one by one.

Albert shrugged again. Smoke from the fire bit at my eyes, and my nostrils filled with the smell of roasting meat. The women in the crowd had resumed their high-pitched singing, and the drumming rose in volume with them. A wizened, toothless old man shoved a gourd in front of my face, and the vinegary smell of palm wine momentarily displaced the smoke and the aroma of the meat. I grabbed the gourd and took a sip from it and shivered from the sudden effect, felt my heart race, and found the courage to make my way quickly through the lively crowd towards the hut.

I passed through the low doorway and stood inside. It was dark, and I thought I was alone in the room. Tricked. A prisoner. The hut was stifling hot, the air heavy with the sour smell of human sweat. I stepped away from the entrance, let in a band of sunlight, and saw Woodrow seated on a low stool against the far wall. On either side of him, also on low stools, sat the tall, elderly man and the eldest of the four women. The others, including the young woman with the baby, lay on mats on the floor nearby, watching me.

“Woodrow, I hope—”

“Please sit down,” he said, cutting me off. “Welcome.”

I looked around in the dimly lit space and followed the example of the other women and lay my long body down on a mat by the door.

There was silence for a moment, an embarrassing, almost threatening silence, until finally Woodrow said, “This is my father, and this is my mother. They don’t speak English, Hannah,” he added.

The old man and woman seemed to be examining me, but they said nothing, and their somber, inward expressions did not change. It was as if I were being tested, as if everyone knew what was expected of me and were merely waiting to see if I could figure it out on my own. If my ignorance or lack of imagination forced them to tell or show me what was expected, I’d have failed the test. They were an imposing, almost imperious group, but at the same time they were utterly ordinary-looking people. Commoners. Working people. It was the context, the social situation, not their appearance, that gave them their power over me.

Woodrow’s father’s skin was charcoal gray, his face crackled and broken horizontally and vertically with deep lines and crevices. His neck and arms had the diminished look of a man who’d once been unusually muscular and in old age had seen everything inside his skin, even the bones, shrink. His hair was speckled with gray and, except for a few thin tufts on his cheeks and chin, he was beardless. The old woman, Woodrow’s mother, was very dark, like Woodrow, and small and round faced, with a receding chin, also like Woodrow. I could see him in her clearly. In twenty years, the son would look exactly like the mother.

I hadn’t noticed, but Albert, my guide, had followed me inside the hut and was now squatting by the door. Woodrow rattled several quick sentences at him, and the boy leapt to his feet and went back outside, as if dismissed. We continued to sit in silence. I dared not break it. What would I say? Whatever words came from me, I was sure they and my voice would sound like my mother’s — that insecure, coy, jaunty banter she always fell back on when addressing black or working-class people, as exotic to her as the people of Fuama were to me. I waited for one of the Africans to speak, any of them, in any language, it didn’t matter. I longed for the sound of human speech, regardless of whether I could understand it, as long as it wasn’t me doing the talking.

Then suddenly Albert was back, lugging a basket filled with steaming chunks of what looked like roast pork and a handful of palm leaves, which he distributed to everyone, starting with Woodrow and his father. He placed the basket on the ground before Woodrow and disappeared again, returning at once with a large open gourd filled with a thick, gray stew. Woodrow gave him another order, and the boy left again, this time returning carrying a batch of pale Coke bottles filled with what I assumed was palm wine.

At the sight of the food and drink, Woodrow’s father’s expression had changed from unreadable impassivity to obvious delight, and he reached across Woodrow and with one hand grabbed a Coke bottle and with the other picked up his leaf and snatched a piece of the meat from the basket. He took a mouthful of the wine, mumbled what I took to be a quick prayer, and spat a bit of it onto the ground before him, then swallowed, smacking his lips with pleasure. He tore off a large piece of the meat with his teeth and, almost without chewing, swallowed it — his eyes closed in bliss — and then a second large mouthful, and a third, by which time the others had joined him, and the hut filled with the sounds of chewing, slurping, swallowing.

The young woman on the mat opposite me lay back and ate in a leisurely, luxurious way, as if at a Roman banquet, nursing her baby at the same time. She glanced over at me, smiled to herself through half-closed eyes, casually passed a Coke bottle to me, then returned to eating. Woodrow’s sister? His father’s youngest wife? Or Woodrow’s village wife and baby? I didn’t know how to ask and was afraid of the answer. Flies buzzed in the darkness, cutting against the thick, muffled noise of the drums and singing outside. I took a small sip of the wine and as the others had done spat half into the dirt before swallowing. With leaf in hand I plucked a small piece of the pork from the basket.

I glanced around and realized that everyone had ceased chewing and was watching me with friendly but inexplicable eagerness. And then, of course, it came to me. This was bush meat. The skinned beasts roasting on the fire were adult chimpanzees, their heads and hands and feet removed and boiled with their innards for stew, their cooked haunches, shoulders, ribs, and thickly muscled upper arms and legs cut into steaks and chops. It was bush meat — a profoundly satisfying, probably intoxicating, delicacy to be savored in celebration of the return of Fuama’s favorite son and the foreign woman who had agreed to become his wife.

I slowly returned the chunk of meat to the basket, wiped my hand on my dress, and stood up. “Woodrow,I… I’m sorry,” I said. “But I can’t.” His face froze. The others simply stared at me, uncomprehending, confused, as if they and not I had made the terrible mistake. I knew that it was an insult to them, an unforgivable breach of decorum, and Woodrow was being humiliated before his people. But I could no more eat the flesh of that animal than if it had been human flesh. I’m not in the slightest fastidious about what I eat, and have devoured the bodies of animals all my life without a tinge of guilt or revulsion. I’ve eaten snakes and insects, badgers, woodchucks, bison, and ostrich. I could have eaten dog or cat or rat, even, if that were traditional and were expected of me as a way of honoring the hospitality of family and tribe. But not chimpanzee. Not an animal so close to human as to expect from it mother-love and grief, pride and shame, fear of abandonment and betrayal, even speech and song.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.