“Have that mama’s boy Mr. Cringle find you a hammock,” said he, “and tell Squibb to put you to work in the kitchen. You’ll be his shifter and keep the coppers supplied with water and clean. You won’t turn a guinea on this trip, Calhoun, but I’ll wager you’ll be a man’s man when we dock again in New Orleans.”

“Thank you, sir.” I extended my hand. “Like you, sir?”

“Like me?” It seemed to startle him. “Don’t be silly.” He barely touched my palm with his fingers. “No, never like me, Calhoun.”

That was reassuring to me, though he would never realize it. I turned and walked slowly to where Cringle stood on watch, for I was still very weak in the knees, and my stomach had not stabilized either, continuing to chew upon itself as the mate led me through a hatchway on the main deck, then farther down, well below the ship’s waterline, to a soggy pit that assaulted my senses with the odor of old piss riding on the air beside the sickly-sweet stench of decaying timbers. This wet cavity had a name: the orlop, an ammonia-smelling hold with little light and less air, where hammocks swung from mildewed beams and where cargo — sea chests and cable — was stored. He gave me a footlocker and gear, and showed me how to fashion a hammock from sailcloth, but seeing these berths I felt sicker than before. Isadora’s cat-ridden rooms were intolerable, no question of that, but in the Republic’s orlop only an inch of plank separated my boots from the bottom of the sea. “It’s bloody dangerous below,” Cringle said, and you didn’t need a degree in maritime science to see why.

Down there, in the leaking, wishbone-shaped hull, the fusty hold looked darker than the belly of Jonah’s whale; it was divided into a maze of low, layered compartments much like the cross section of an archaeological dig — level upon level of crawl spaces, galleys, and cramped cells so small we barely had enough room to turn around — and, once the forge was going, the forecastle cookroom, where I was to work, was hotter than the griddles of Hell. Cockroaches I saw everywhere. And rats. All this, however, was like a hotel suite when compared to the head. It consisted of twelve splintery boards in the bows — a shipboard pissoir impossible to use in a rough sea because the foul, malarial soup of human feces from intestines twisted by flux flew up round your feet and splattered overhead when the ship met a head sea. “Either this,” Cringle said, keeping his mouth covered with one hand, “or swing your black arse over the side, as the skipper and I do.” His eyes watering, he motioned me to climb back up. “After a month that side of the ship’s so rank the authorities at Bangalang make us clean it before we can put to port.”

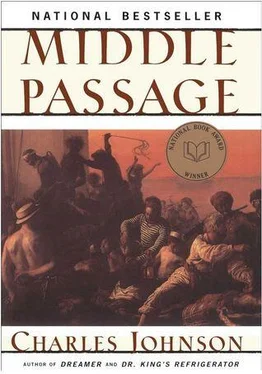

All in all, she was a typical ship, I learned those first few days from Cringle, and by this he meant she was stinking and wet, with sea scurvy and god-awful diseases rampant; but even queerer than all this — strange to me, at least — the Republic was physically unstable. She was perpetually flying apart and re-forming during the voyage, falling to pieces beneath us, the great sails ripping to rags in high winds, the rot, cracks, and parasites in old wood so cancerously swift, springing up where least expected, that Captain Falcon’s crew spent most of their time literally rebuilding the Republic as we crawled along the waves. In a word, she was, from stem to stern, a process. She would not be, Cringle warned me, the same vessel that left New Orleans, it not being in the nature of any ship to remain the same on that thrashing Void called the Atlantic. (Also called the Ethiopic Ocean by some, owing to the trade.) And a seaman’s first duty was to keep her afloat at any cost.

His second duty was to stay drunk. Every man “knew the ropes”—specifically, the sheets and halyards that controlled the sails; each knew the ship’s parts and principles, and any one of them, from the boatswain’s mate to the cabin boy Tom, could undertake the various duties involved — to hand, reef, or steer — but only a fool would stay sober when he wasn’t on watch. The whole Middle Passage, you might say, was one long hangover. It had the character of a four-month binge. And the biggest sot of all, I discovered, the most pitiful rumpot, was Josiah Squibb. Stepping timidly into the grimy cookroom after Cringle left me, my arms over my head in case Squibb pegged something at me for stealing his papers, I found the adjacent spirit room open and Squibb as polluted as I’d left him in the tavern. The poor devil’s head lay on a long table littered with strips of salt pork and bricklike biscuits double-baked back on shore. His parrot was drunk too, but his voice was not as faint as Squibb’s, who was in that advanced stage of alcoholic stupor that severs mind from body, both his eyeballs large as eggs, and glaring blankly into a mug of warm beer, as drunks often do, talking to his reflection. “Josiah,” he sniffed. Then answered: “Yes?” “If yuh wants respect, darlin’, yuh got to leave the ruddy cup alone, yes yuh do. Yuh wants ’em to respect yuh now, don’t yuh?” “Yes,” he said, “yes, I do. . ”

“’H’lo?” I stepped closer. “Mr. Squibb, are you all right, sir?”

“Do I look all right?” He sat scratching under one arm, squinting to see me more clearly. “I’m a wee bit drunk with dinner to fix, and so help me I can’t do it!” The movement of looking up tipped him backward (the ship veering larboard didn’t help either), and I was obliged to catch him under his armpits, then pitch him forward. He let his head hang. “Fix me some blackstrap, will ye, then finish up this mess.”

“But I’ve never—”

“Do it.” Squibb filled his cheeks with wind, then he swallowed. “I’ll show ye how.”

Following his orders, I helped him prepare mess, and mess it was, for the biscuits were hard and full of weevils (“I left two teeth in one of ’em this morning,” said Squibb), the salt beef tasted of the barrel in which it had been packed, not being helped very much by the onions and peppers I added, and would have been intolerable if not for the beer — each crewman, he said, consumed a gallon a day, but in Squibb’s case it was more like three. He was, had been, an alcoholic since his first voyage at the age of eleven, though he wasn’t exactly certain of his age, and precious little else when he was pickled, which was every waking hour, as it turned out. His lips kept the set smile of a lush. There was no risk in his recognizing me from the tavern; he had trouble keeping track of my identity from one hour to the next. And, sad to say, this was probably Squibb’s last voyage. Only a slaver would have him. His right foot was dead. He’d drunkenly stepped off a mizzentop during his last trip, having forgotten where he was, fallen twenty feet, and miraculously landed on his right foot. Which shattered. Where bone had been, Squibb now had a metal rod. He limped, of course. Like most fat people he wore his shirt outside his trousers whenever possible. He was slow, useless except in the cookroom, with lumps and udders in his face from liquor; a liability at sea, but what sailor could not see in Josiah Squibb his own portrait in years to come if Providence turned her back? As for his parrot, he was more or less the cook’s shadow, having his bawdy humor, and even asked me occasionally, “You had any lately, mate?”

“Aye,” said Squibb, sipping blackstrap as I slopped salmagundi into buckets to haul to the great cabin. “I’ve seen some things, laddie. Reason I look so bad is ’cause I’ve been livin’.”

That made me pause in the doorway. Like Captain Falcon, like me and so many other people (except Isadora), he seemed to hunger for “experience” as the bourgeois Creoles desired possessions. Believing ourselves better than that, too refined to crave gross, physical things, we heaped and hived “experiences” instead, as Madame Toulouse filled her rooms with imported furniture, as if life was a commodity, a thing we could cram into ourselves. I was tempted to ask about his “experiences,” to have him share and display them before me like show-and-tell at school. Instead, I asked:

Читать дальше