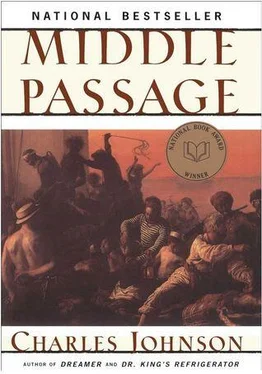

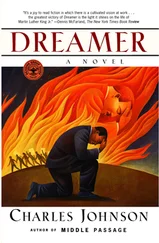

Charles Johnson

Middle Passage

To Joan

for the last twenty-two years

Homo est quo dammodo omnia

Saint Thomas Aquinas

What port awaits us, Davy Jones’

or home? I’ve heard of slavers drifting, drifting,

playthings of wind and storm and chance,

their crews

gone blind, the jungle hatred

crawling up on deck.

Robert Hayden, “Middle Passage”

Who sees variety and not the Unity wanders

on from death to death

Brihad-aranyaka Upanishad

Laud Deo

Journal of a Voyage intended

by God’s permission

in the Republic, African

from New Orleans to the Windward

Coast of Africa

Entry, the first JUNE 14, 1830

Of all the things that drive men to sea, the most common disaster, I’ve come to learn, is women. In my case, it was a spirited Boston schoolteacher named Isadora Bailey who led me to become a cook aboard the Republic . Both Isadora and my creditors, I should add, who entered into a conspiracy, a trap, a scheme so cunning that my only choices were prison, a brief stay in the stony oubliette of the Spanish Calabozo (or a long one at the bottom of the Mississippi), or marriage, which was, for a man of my temperament, worse than imprisonment — especially if you knew Isadora. So I went to sea, sailing from Louisiana on April 14, 1830, hoping a quarter year aboard a slave clipper would give this relentless woman time to reconsider, and my bill collectors time to forget they’d ever heard the name Rutherford Calhoun. But what lay ahead in Africa, then later on the open, endless sea, was, as I shall tell you, far worse than the fortune I’d fled in New Orleans.

New Orleans, you should know, was a city tailored to my taste for the excessive, exotic fringes of life, a world port of such extravagance in 1829 when I arrived from southern Illinois — a newly freed bondman, my papers in an old portmanteau, a gift from my master in Makanda — that I dropped my bags and a shock of recognition shot up my spine to my throat, rolling off my tongue in a whispered, “Here, Rutherford is home.” So it seemed those first few months to the country boy with cotton in his hair, a great whore of a city in her glory, a kind of glandular Golden Age. She was if not a town devoted to an almost religious pursuit of Sin, then at least to a steamy sexuality. To the newcomer she was an assault of smells: molasses commingled with mangoes in the sensually damp air, the stench of slop in a muddy street, and, from the labyrinthine warehouses on the docks, the odor of Brazilian coffee and Mexican oils. And also this: the most exquisitely beautiful women in the world, thoroughbreds of pleasure created two centuries before by the French for their enjoyment. Mulattos colored like magnolia petals, quadroons with breasts big as melons — women who smelled like roses all year round. Home? Brother, for a randy Illinois boy of two and twenty accustomed to cornfields, cow plops, and handjobs in his master’s hayloft, New Orleans wasn’t home. It was Heaven. But even paradise must have its back side too, and it is here (alas) that the newcomer comes to rest. Upstream there were waterfront saloons and dives, a black underworld of thieves, gamblers, and ne’er-do-wells who, unlike the Creoles downstream (they sniffed down their long, Continental noses at poor, purebred Negroes like myself), didn’t give a tinker’s damn about my family tree and welcomed me as the world downstream would not.

In plain English, I was a petty thief.

How I fell into this life of living off others, of being a social parasite, is a long, sordid story best shortened for those who, like the Greeks, prefer to keep their violence offstage. Naturally, I looked for honest work. But arriving in the city, checking the saloons and Negro bars, I found nothing. So I stole — it came as second nature to me. My master, Reverend Peleg Chandler, had noticed this stickiness of my fingers when I was a child, and a tendency I had to tell preposterous lies for the hell of it; he was convinced I was born to be hanged and did his damnedest to reeducate said fingers in finer pursuits such as good penmanship and playing the grand piano in his parlor. A Biblical scholar, he endlessly preached Old Testament virtues to me, and to this very day I remember his tedious disquisitions on Neoplatonism, the evils of nominalism, the genius of Aquinas, and the work of such seers as Jakob Böhme. He’d wanted me to become a Negro preacher, perhaps even a black saint like the South American priest Martín de Porres — or, for that matter, my brother Jackson. Yet, for all that theological background, I have always been drawn by nature to extremes. Since the hour of my manumission — a day of such gloom and depression that I must put off its telling for a while, if you’ll be patient with me — since that day, and what I can only call my older brother Jackson’s spineless behavior in the face of freedom, I have never been able to do things halfway, and I hungered — literally hungered —for life in all its shades and hues: I was hooked on sensation, you might say, a lecher for perception and the nerve-knocking thrill, like a shot of opium, of new “experiences.” And so, with the hateful, dull Illinois farm behind me, I drifted about New Orleans those first few months, pilfering food and picking money belts off tourists, but don’t be too quick to pass judgment. I may be from southern Illinois, but I’m not stupid. Cityfolks lived by cheating and crime. Everyone knew this, everyone saw it, everyone talked ethics piously, then took payoffs under the table, tampered with the till, or fattened his purse by duping the poor. Shameless, you say? Perhaps so. But had I not been a thief, I would not have met Isadora and shortly thereafter found myself literally at sea.

Sometimes after working the hotels for visitors, or when I was drying out from whiskey or a piece of two-dollar tail, I would sneak off to the waterfront, and there, sitting on the rain-leached pier in heavy, liquescent air, in shimmering light so soft and opalescent that sunlight could not fully pierce the fine erotic mist, limpid and luminous at dusk, I would stare out to sea, envying the sailors riding out on merchantmen on the gift of good weather, wondering if there was some far-flung port, a foreign country or island far away at the earth’s rim where a freeman could escape the vanities cityfolk called self-interest, the mediocrity they called achievement, the blatant selfishness they called individual freedom — all the bilge that made each day landside a kind of living death. I don’t know if you’ve ever farmed in the Midwest, but if you have, you’ll know that southern Illinois has scale; fields like sea swell; soil so good that if you plant a stick, a year later a carriage will spring up in its place; forests and woods as wild as they were before people lost their pioneer spirit and a healthy sense of awe. Only here, on the waterfront, could I recapture that feeling. Wind off the water was like a fist of fresh air, a cleansing blow that made me feel momentarily clean. In the spill of yellow moonlight, I’d shuck off my boots and sink both feet into the water. But the pier was most beautiful, I think, in early morning, when sunlight struck the wood and made it steam as moisture and mist from the night before evaporated. Then you could believe, like the ancient philosopher Thales, that the analogue for life was water, the formless, omnific sea. Businessmen with half a hundred duties barnacled to their lives came to stare, longingly, at boats trolling up to dock. Black men, free and slave, sat quietly on rocks coated with crustacea, in the odors of oil and fish, studying an evening sky as blue as the skin of heathen Lord Krishna. And Isadora Bailey came too, though for what reason I cannot say — her expression on the pier was unreadable — since she was, as I soon learned, a woman grounded, physically and metaphysically, in the land. I’d tipped closer to her, eyeing the beadpurse on her lap, then thought better of boosting it when I was ambushed by the innocence — the alarming trust — in her eyes when she looked up at me. I wondered, and wonder still: What’s a nice girl like her doing in a city like this?

Читать дальше