I had to admit that I had not.

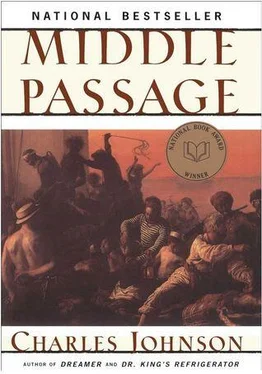

“Don’t feel bad.” His smile vanished. “Few men have. Arab traders will bring them from the interior, I’m told, because no European has been to their village and lived to tell of it. They are an old people. Older, some say, than the!Kung Tribe of Southern Africa, people who existed when the planet — the galaxy, even — was a ball of fire and steam. And not like us at all. No, not like you either, though you are black. In all the records there is but one sentence about these Allmuseri, and that from a Spanish explorer named Rafael García, whose home is now an institution for the incurably insane in Havana.” He was silent again, biting down hard on the stem of his pipe. “I do not feel good about this cargo, Calhoun.”

“That sentence,” I asked him. “What did Garcia say?”

Cringle stared back to the sea, leaning on the rail, his voice blurred, then obliterated by the wind; I had to strain to hear him. “Sorcerers!” he said. “They’re a whole tribe — men, women, and tykes — of devil-worshiping, spell-casting wizards.”

Entry, the third JUNE 23, 1830

Forty-one days after leaving New Orleans, we coasted in on calm waters, a breeze at our backs, and the skipper set all hands to unmooring the ship, bringing her slowly like a hearse to anchorage alongside the trading post at Bangalang. It was a rowdy fort, all right. Cringle told me the barracoons were built by the Royal African Company in 1683—one of several well-fortified western forts always endangered by hostile, headhunting natives nearby, by competing merchants, and over two centuries residents at the fort had fought first the Dutch, then the French for control of Negro slaves. Lately, it had fallen into the soft, uncallused hands of Owen Bogha, the halfbreed son of a brutal slave trader from Liverpool and the black princess of a small tribe on the Rio Pongo. He was a sensualist. A powdered fop and Anglophile who dyed his chest and pubic hairs blond and, as did other men of the day plagued by head lice big as beans, shaved his pate and wore perfumed wigs. Educated in England, this man Bogha, who greatly enjoyed wealth and the same gaming tables played by Captain Falcon in Paris, returned to take advantage of his father’s property and mother’s prestige in Bangalang, overseeing from his great hilltop home the many warehouses, bazaars, harems, and Moslem caravans that crawled from the interior during the Dry Season. The skipper stayed at his home most nights, consuming stuffed fish and raisin wine, and giving Bogha news of “civilization” back in England and America — he was starving for news, claimed Bogha, in this filthy, Godforsaken hole. And Cringle, being an officer, was invited too, but said he couldn’t abide flesh merchants; in fact, he abhorred everything about Bangalang, and slept instead with the rest of the crew on deck in the open air to escape the heat below.

As for myself, I was simply glad to be ashore. It had been unsettling and claustrophobic, out there with the ship cleaving waves the color of root medicine, soughing wind that broke the spider-web tracery of rigging like thread, and the sky and sea blurred together into a pewter gray gloom without a stitch, without outlines, without a bottom to their depths, and sometimes, when we could not see the horizon and sailed through endless fog and shifting mist, I’d felt such dizzying entrapment — of being deprived of such basic directions as left and right, up and down — that I screamed myself awake some nights, choking on the rank male sweat that hung around my hammock like wet clothing. I ached from cleaning pots in the cookroom, and I’d grown tired of my clothes being so perpetually wet from deckwash, the slap of rainwind, and leaks in the orlop that once I had the feeling that the toes on my left foot were webbed. On top of that, Cringle had shouted at me so often for being slow, or asleep during my watch, that I could tell you which of his teeth had been worked on in Boston or Philadelphia, pulled in another city or by a dentist in New Orleans. I wished in vain for dry breeches, floorboards that didn’t move, a bowl of warm milk at bedtime, and sometimes — aye — for Isadora. Worse, I kept a light cold, and my incessant coughing gave me headaches. Even so, I could not join the others in their banter after we lowered anchor, or even drink with much gusto — stale beer gave me the johnnytrots — but simply lie quietly in my bunk, wondering if in a single fantastic evening I had become Captain Ebenezer Falcon’s shipboard bride.

I could express this fear to no one, and I beg you to keep it to yourself. His courtship of me, for so it must be called, began the night Falcon caught me rummaging through his cabin. This was not an easy situation to explain away. Especially after what I learned from his papers, ledgers, and journal. Somehow I’d miscalculated. According to his schedule, the skipper should have been at the fort all evening, unloading four skiffs freighted with clothing and beads, liquor, and utensils of brass and pewter for the notorious Arab trader Ahman-de-Bellah, whose first caravan of captured Negroes from eight, maybe nine tribes, was herded into Bangalang a few hours before. Falcon’s curtains were drawn. His door was padlocked. Of course that presented no problem for me.

Slipping away from my watch and into his room, easing his door shut with my fingertips, I felt the change come over me, a familiar, sensual tingle that came whenever I broke into someone’s home, as if I were slipping inside another’s soul. Everything must be done slowly, deliberately, first the breath coming deep from the belly, easily, as if the room itself were breathing, limbs light like hollow reeds, free of tension, all parts of me flowing as a single piece, for I had learned in Louisiana that in balletlike movements there could be no error of the body, no elbows cracking into chair arms in a stranger’s space to give me away. Theft, if the truth be told, was the closest thing I knew to transcendence. Even better, it broke the power of the propertied class, which pleased me. As a boy I’d never had enough of anything. Yes, my brother Jackson and I lived close to our master, but on the Makanda farm during the leaner years, life was, as old bondwomen put it, “too little too late.” At suppertime: watery soup and the worst part of the hog and so little of that that Jackson often skipped meals secretly so I could have a little bit more. If you have never been hungry, you cannot know the either/or agony created by a single sorghum biscuit — either your brother gets it or you do. And if you do eat it, you know in your bones you have stolen the food straight from his mouth, there being so little for either of you. This was the daily, debilitating side of poverty that no one speaks of, the perpetual scarcity that, at every turn, makes the simplest act a moral dilemma. On a nearby farm there lived a slave father and his two sons who had one blouse and pair of breeches among them, so that when one went off to work the others were left naked and had to hide at home in their shed. True enough, Jackson and I fared better than they, but in linen handed down by Reverend Chandler or by his pious friends — who no doubt felt good about the very charity that annihilated me — in their scented waistcoats and smelly boots I whiffed the odor of other men, even heard their accents echo in the very English I spoke, as if I was no one — or nothing — in my own right, and I wondered how in God’s name you could have anything if circumstances threw you amongst the had. Ah, me. The Reverend’s prophecy that I would grow up to be a picklock was wiser than he knew, for was I not, as a Negro in the New World, born to be a thief? Or, put less harshly, inheritor of two millennia of things I had not myself made? But enough of this.

Читать дальше