"I don't agree with you," replied I. "He looks even younger in this uniform."

Grushnitsky could not bear this thrust, for like all boys he lays claim to being a man of some years. He thinks that the deep traces of passion on his face can pass for the stamp of age. He threw a furious look at me, stamped his foot, and strode away.

"You must admit," I said to the princess, "that although he has always been very ridiculous he struck you as interesting only a short while ago... in his gray overcoat."

She dropped her eyes and said nothing.

Grushnitsky pursued the princess the whole evening, dancing either with her or vis-а-vis . He devoured her with his eyes, sighed and wearied her with his supplications and reproaches. By the end of the third quadrille she already hated him.

"I didn't expect this of you," he said, coming up to me and taking me by the arm.

"What are you talking about?"

"Are you going to dance the mazurka with her?" he asked me in a solemn tone. "She admitted as much to me..."

"Well, what of it? Is it a secret?"

"Of course... I should have expected it from that hussy, that flirt... Never mind, I'll take my revenge!"

"Blame your overcoat or your epaulets, but why accuse her? Is it her fault that she no longer likes you?"

"Why did she give me reason to hope?"

"Why did you hope? To want something and to strive for it, that I can understand, but whoever hopes?"

"You have won the bet, but not entirely," he said, with a spiteful sneer.

The mazurka began. Grushnitsky invited none but Princess Mary. Other cavaliers chose her every minute. It was obviously a conspiracy against me-but that was all for the better. She wanted to talk with me; she was prevented from doing so-good! She would want to all the more.

I pressed her hand once or twice; the second time she pulled her hand away without a word.

"I will sleep badly tonight," she said to me when the mazurka was over.

"Grushnitsky is to blame for that."

"Oh no!" And her face grew so thoughtful, so sad, that I promised myself I would certainly kiss her hand that night.

Everybody began to disperse. Having helped the princess into her carriage, I quickly pressed her little hand to my lips. It was dark and no one could see.

I returned to the ballroom, highly pleased with myself.

The young gallants were having supper around a large table, Grushnitsky among them. When I entered they all fell silent; they must have been talking about me. Ever since the previous ball many of them, the captain of dragoons in particular, have had a bone to pick with me, and now it seems that a hostile band is being organized against me under Grushnitsky's command. He wears such a cocky air of bravura.

I am very glad of it, for I love enemies, though not in the Christian way. They amuse me and quicken my pulse. To be always on one's guard, to catch every look and the significance of every word, to guess intentions, foil conspiracies, pretend to be deceived and then to overthrow with a single blow the whole vast edifice of artifice and design raised with so much effort-that is what I call life.

Throughout the meal Grushnitsky spoke in whispers and exchanged winks with the captain of dragoons.

This morning Vera left for Kislovodsk with her husband. Their carriage passed me as I was on my way to Princess Ligovskaya's. She nodded to me-there was reproach in her eyes.

Who is to blame, after all? Why doesn't she not want to give me an opportunity to see her alone? Love, like fire, dies out without fuel. Perhaps jealousy will succeed where my pleadings have failed.

I stayed a whole hour at the princess's. Mary didn't come down-she was indisposed. In the evening she didn't appear on the boulevard. The newly formed gang had armed itself with eyeglasses with little handles and looked formidable indeed. I am glad that the young princess was ill, for they would have affronted her in some way. Grushnitsky's hair was messed up, and he looked desperate; he actually seems to be embittered, his vanity especially has been wounded. But some people are really amusing even in despair!

On returning home I felt a vague longing. I had not seen her! She was ill! Have I actually fallen in love? What nonsense!

At eleven o'clock in the morning, at which hour Princess Ligovskaya usually sweats it out at the Yermolov baths, I walked past her house. Princess Mary was sitting at the window lost in thought. On seeing me, she jumped to her feet.

I walked into the waiting room. There was no one around and, taking advantage of the freedom of the local customs, I went straight to the drawing room without being announced.

A dull white had spread over the princess's charming features. She stood by the piano, leaning with one arm on the back of a chair; the hand trembled slightly. Quietly I walked up to her and said: "Are you angry with me?"

She raised her eyes to me with a deep, languorous look and shook her head. Her lips wanted to say something, but could not. Her eyes filled with tears. She sank into a chair and covered her face with her hands.

"What is the matter?" I said, taking her hand.

"You don't respect me! Oh, leave me alone!"

I stepped back a few paces. She stiffened in the chair and her eyes flashed...

I paused, my hand on the door knob, and said: "I beg your pardon, Princess! I acted rashly... it will not happen again, I'll see to it. Why should you know what has been going on in my heart? You'll never know it, which is all the better for you. Farewell."

As I went out I thought I heard her sobbing.

Until evening I wandered about the outskirts of Mashuk, tired myself out thoroughly and, on returning home, flung myself on the bed in utter exhaustion.

Werner dropped in to see me.

"Is it true," he asked, "that you intend to marry the young Princess Ligovskaya?"

"Why do you ask?"

"The whole town is talking about it. All my patients can think of nothing else but this important news, and these watering-place people know everything!"

"This is Grushnitsky's little joke!" thought I.

"To prove to you, doctor, how unfounded these rumors are, I will tell you in confidence that I am moving on to Kislovodsk tomorrow."

"And Princess Mary as well?"

"No, she will remain here another week."

"So you don't intend to marry?"

"Doctor, doctor! Look at me: do I look like a bridegroom or anything of the kind?"

"I am not saying you do... But, you know, it sometimes happens," he added, smiling slyly, "that a man of honor is obliged to marry, and that there are fond mamas who at any rate do not prevent such things from arising... So as a friend, I advise you to be more cautious. The air is highly dangerous here at the waters. How many splendid young men worthy of a better fate have I seen leave here bound straight for the altar. Believe it or not, they even wanted to marry me off too. It was the doing of one provincial mama with a very pale daughter. I had the misfortune to tell her that the girl would regain her color after marriage; whereupon, with tears of gratitude in her eyes, she offered me her daughter's hand and all her property – fifty souls [100] economically too small a feudal estate with that many serfs or as they were called "souls".

, I believe it was. I told her, however, that I was quite unfit for matrimony."

Werner left fully confident that he had given me a timely warning.

From what he had said I gathered that many malicious rumors had been spread all over town about Princess Mary and myself: Grushnitsky will have to pay for this!

It is three days since I arrived in Kislovodsk. I see Vera every day at the spring or on the promenade. When I wake up in the morning I sit at the window and direct eyeglasses at her balcony. Having dressed long before, she waits for the signal agreed upon, and we meet as if by accident in the garden, which slopes down to the spring from our houses. The invigorating mountain air has brought the color back to her cheeks and given her strength. It is not for nothing that Narzan [101] famous Caucasian mineral water. In the Kabardian language, nart-sane means drink of the Narts, mythical giants or heroes.

is called the source of heroes. The local inhabitants claim that the air in Kislovodsk is conducive to love and that all the love affairs that ever began at the foot of Mashuk have invariably reached their ending here. And, indeed, everything here breathes of seclusion. Everything is mysterious-the dense shadows of the lime trees bordering the torrent which, falling noisily and frothily from flag to flag, cuts its way through the green mountains, and the gorges, full of gloom and silence, that branch out from here in all directions. And the freshness of the fragrant air, laden with the aroma of the tall southern grasses and the white acacia [102] actually, the imported American black locust tree, which has beautiful white flowers this time of year.

, and the incessant deliciously drowsy babble of the cool brooks which, mingling at the end of the valley, rush onward to hurl their waters into the Podkumok River. On this side the gorge is wider and spreads out into a green depression, and through it meanders a dusty road. Each time I look at it, I seem to see a carriage approaching and a pretty rosy-cheeked face looking out of its window. Many a carriage has already rolled along that road – but there still is no sign of that particular one. The settlement beyond the fort is now densely populated; from the restaurant, built on a hill a few paces from my apartment, lights have begun to glimmer in the evenings through the double row of poplars, and the noise and the clinking of glasses can be heard until late at night.

Читать дальше

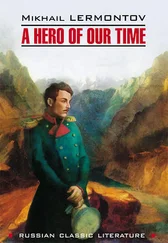

![Михаил Лермонтов - A Hero of Our Time [New Translation]](/books/27671/mihail-lermontov-a-hero-of-our-time-new-translati-thumb.webp)