The wives of the local officials, the hostesses of the springs, so to speak, were more graciously inclined. They carry eyeglasses [83] we couldn't bear to use the term "lorgnette," a sort of magnifying spectacle often with a little handle, used to see at a distance, as at the opera or to make an impression on someone.

with handles and pay less attention to the uniform, for in the Caucasus they have learned to find ardent hearts under brass buttons and enlightened minds under white army caps. These ladies are very charming, and remain charming for a long time! Their admirers are renewed every year, which. perhaps explains the secret of their endless good nature. As I climbed up the narrow path leading to Elizabeth Spring I passed a crowd of men, both civilians and military, who, as I discovered later, form a class in itself among those who wait for the movement of the waters. They drink, but not water, go out but little, make love for amusement in a half-hearted way-they gamble and complain of boredom. They are dandies. They assume affected poses as they dip their wickered glasses into the sulfur water. The civilians show off pale-blue neckties, and the army men, ruffs showing above their collars. They express a deep disdain for provincial society and sigh at the thought of the aristocratic drawing rooms of the capital, which don't accept them.

Here at last is the well... On a site nearby, a little red-roofed building has been raised over the baths, and further on, a porch to shelter the promenaders when it rains. Several wounded officers-pale, sad-looking men-sat on a bench holding their crutches in front of them. Several ladies were briskly pacing back and forth, waiting for the water to take effect. Among them were two or three pretty faces. Through the avenues of vines that cover the slope of Mashuk I caught occasional glimpses of variegated bonnets that evidently belonged to seekers of solitude for two, since each bonnet was invariably accompanied by an army cap or an ugly round hat. On a steep cliff where there is a pavilion named the Aeolian Harp, sightseers were training a telescope on Elbrus [80] spa town on river about 60 miles west of Yekateringrad and north of the Caucasus and its highest peak, Mt. Elbrus. Lermontov was killed in a duel here. A spa is a place with mineral water springs thought to have healing properties and thus frequented by wounded soldiers or other sick or old people. It was a good place to mix and form new social relationships and so a suitable place for a novel. Finally, this type of society gathering was usual in the society novels that Lermontov effectively puts paid to in this segment (the Encyclopædia Brittanica article on Lermontov seems to miss the point of its irony entirely).

. Among them were two tutors with their charges who had come here in search of a cure for scrofula [82] swelling of the glands.

.

Panting, I had stopped at the brow of the hill and was leaning against a corner of the building surveying the picturesque scene, when I suddenly heard a familiar voice behind me: "Pechorin! Been here long?"

I turned around and saw Grushnitsky. We embraced. I had met him in a front-line unit. He had a bullet wound in the leg and had left for the watering place a week earlier than I.

Grushnitsky is a cadet. He has served only a year and wears a heavy soldier's overcoat which he shows off as his particular brand of foppery. He has a soldier's Cross of St George. He is well-built, dark-faced and dark-haired, and looks twenty-five though he can scarcely be more than twenty-one. He has a way of throwing his head back when talking, and he constantly twirls his mustache with his left hand, for with his right he leans on his crutch. His speech is glib and florid; he is one of those people who have a pompous phrase ready for every occasion, who are unmoved by simple beauty and who grandly assume a wrap of extraordinary emotions, exalted passions and exquisite anguish. They delight in creating an impression, and romantic provincial ladies are infatuated with them to the point of distraction. In their old age they become either peaceable landlords or drunkards, sometimes both. They are often endowed with many good qualities, but they have not an ounce of poetry in their souls. Grushnitsky used to have [84] Nabokov notes the tendency as here to veer into the past tense as if someone – maybe Pechorin? – is trying out this character for a role in a play or a book.

a passion for declaiming-he would shower you with words as soon as the conversation transcended the bounds of everyday matters, and I could never argue with him. He neither answers your rebuttal nor listens to what you have to say. As soon as you stop, he launches upon a long tirade which on the face of it seems to have some bearing on what you have said, but actually amounts only to a continuation of his own argument.

He is rather witty and his epigrams are frequently amusing but never pointed or malicious-he will never annihilate a person with a single word. He knows neither people nor their weak spots, for all his life he has been preoccupied with himself alone. His object in life is to become the hero of a romance. So often has he tried to make others believe he is a being never intended for this world and hence doomed to some kind of occult suffering that he has practically convinced himself of it. That is why he shows off his heavy soldier's overcoat. I see through him and he dislikes me for it, though on the face of it we are on the friendliest of terms. Grushnitsky has a reputation for superb courage. I have seen him in action: he brandishes his saber, and dashes forward shouting with his eyes shut. There is something very un-Russian in that brand of gallantry!

I don't like him either, and I feel we are bound to fall foul of each other one day with sorry consequences for one of us.

His coming to the Caucasus too was the result of his romantic fanaticism. I am certain that on the eve of his departure from his father's village he tragically announced to some pretty neighbor that he was not going merely to serve in the army, but to seek death, because... at this point he probably covered his eyes with his hand and went on like this: "No, you must not know the reason! Your pure soul would shudder at the thought! And why should you? What am I to you? Could you understand me?" and so on and so forth.

He told me himself that the reason why he enlisted in the K- regiment will forever remain a secret between him and his Maker.

And yet when he discards his tragic role, Grushnitsky can be quite pleasant and amusing. I would like to see him in the company of women, for I imagine that's when he'd try to be at his best.

We greeted each other as old friends. I began to ask him many questions concerning life at the spa and the interesting people there were to be met.

"We lead a rather prosaic life," he sighed. "Those who drink the waters in the mornings are listless like all invalids, and those who drink wine in the evenings are unbearable like all people who enjoy good health. There is feminine company, but it offers little consolation. They play whist, dress badly and speak terrible French. This year Princess Ligovskaya with her daughter are the only visitors from Moscow, but I haven't met them. My overcoat is like a brand of ostracism. The sympathy it evokes is as unwelcome as charity."

Just then two ladies walked past us toward the spring, one middle-aged, the other young and slender. I couldn't see their faces for the bonnets, but they were dressed in strict conformity with the very best taste: everything was as it should be. The young woman wore a high-necked pearl-gray dress. A dainty silk scarf encircled her supple neck. A pair of dark-brown shoes encased her slender little feet up to the ankles so daintily that even one uninitiated into the mysteries of beauty would have caught his breath, if only in amazement. Her light but dignified gait had something virginal about it that eluded definition yet was tangible enough to the eye. As she walked past us, that subtle fragrance was wafted from her which sometimes is exhaled by a billet-doux [85] French for love-letters.

from a charming woman.

Читать дальше

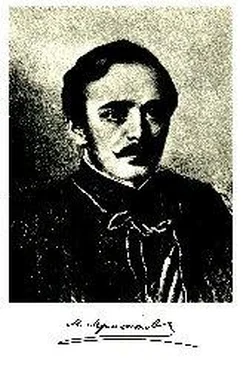

![Михаил Лермонтов - A Hero of Our Time [New Translation]](/books/27671/mihail-lermontov-a-hero-of-our-time-new-translati-thumb.webp)