Firstly, they didn't laugh when he did. Have you ever had opportunity to observe this peculiarity in some people? It's a sign either of evil nature or of deep constant sadness. They shone with a phosphorescent glow, if one may so put it, under half-closed eyelids. It was no reflection of spiritual warmth or fertile imagination. It was the flash of smooth steel, blinding but cold. His glance was brief but piercing and oppressive, it had the disturbing effect of an indiscreet question, and might have seemed audacious had it not been so calmly casual. Perhaps all these observations came to my mind only because I happened to know some details about his life, and another person might've obtained an entirely different impression, but since you won't learn about him from anyone else, you'll have to be satisfied with this portrayal. I must say in conclusion that, on the whole, he was handsome indeed and had one of those unusual faces that are particularly pleasing to society ladies.

The horses were harnessed, the bell attached to the shaft bow tinkled, and the valet had already reported twice to Pechorin that the carriage was waiting. But still there was no sign of Maksim Maksimich. Luckily Pechorin was deep in thought. He stared at the blue jagged ridge of the Caucasus, apparently in no hurry to be on his way. I crossed over to him. "If you would care to wait a while," I said, "you will have the pleasure of meeting an old friend…"

"Ah, that's right!" he replied quickly. "I was told about him yesterday. But where is he?" I looked out over the square and saw Maksim Maksimich running towards us for all he was worth... In a few minutes he had reached us. He could barely catch his breath, beads of perspiration rolled down his face, damp strands of gray hair that had escaped from under his cap stuck to his forehead, and his knees shook. He was about to throw his arms around Pechorin's neck, but the latter extended his hand rather coldly, though his smile was pleasant enough. For a moment the captain was taken aback, then he eagerly gripped the hand with both of his. He was still unable to speak.

"This is a pleasure, dear Maksim Maksimich. How are you?" said Pechorin.

"And thou?…And you?…" faltered the old man, tears welling up in his eyes. "It's a long time... a very long time... But where are you off to?"

"On my way to Persia... and then farther…"

"Not immediately, I hope? Won't you stay awhile, my dear man? We haven't seen each other for so long..."

"I must go, Maksim Maksimich," was the reply.

"My God, what's the hurry? I have so much to tell you and so many questions to ask... How are things, anyway? Retired, eh? What have you been doing?"

"I've been bored stiff," replied Pechorin, smiling.

"Remember our life in the fort? Wonderful hunting country, wasn't it? How you loved to hunt! Remember Bela?"

Pechorin turned white a little and turned away.

"Yes, I remember," he said, deliberately yawning almost in the same breath.

Maksim Maksimich urged him to stay on for another hour or two. "We'll have a fine dinner," he said. "I have two pheasants and the Kakhetian here is excellent... not the same as in Georgia, of course, but the best to be had here. And we could talk... you'll tell me about your stay in St. Petersburg, won't you?"

"I really have nothing to tell, dear Maksim Maksimich. And I have to say goodbye now, for I must be off... In rather a hurry... It was kind of you not to have forgotten me," he added, taking the old man's hand.

The old man frowned. He was both grieved and hurt, though he did his best to conceal his feelings. "Forgotten!" he muttered. "No, I've forgotten nothing. Oh well, never mind... Only I didn't expect our meeting would be like this."

"Come, now," said Pechorin, embracing him in a friendly way. "I don't think I have changed. Ar any rate, it can't be helped. We all are destined to go our several ways. God knows whether we'll meet again." This he said as he climbed into the carriage and the coachman was already gathering up the reins.

"Wait a minute, wait a minute!" Maksim Maksimich suddenly shouted, holding the carriage door. "It completely slipped my mind... I still have your papers, Grigoriy Aleksandrovich... Been carrying them around with me... Thought I'd find you in Georgia, never dreaming the Lord would have us meet here... What do you want me to do with them?"

"Whatever you want," replied Pechorin. "Farewell!"

"So you are off to Persia... When do you expect to be back?" Maksim Maksimich shouted after him.

The carriage was already some distance off, but Pechorin waved in a way that could well be interpreted to mean: "I doubt whether I will return, nor is there any reason why I should!"

Long after the tinkling of the bell and the clatter of wheels against the flinty surface of the road had faded into the distance, the poor old fellow stood glued to the spot, lost in thought.

"Yes," he said at last, trying his best to preserve a nonchalant air though tears of disappointment still showed in his eyes, "we were friends, of course, but what's friendship nowadays? What am I to him? I'm neither rich nor titled, and besides, I'm much older. What a dandy his visit to St. Petersburg has made him! Look at that carriage, and the pile of luggage... and the haughty valet!" This he said with an ironic smile. "Tell me," he went on, turning to me, "what do you think of it all! What sort of a demon is driving him to Persia now? Ridiculous, isn't it? I knew all along, of course, that he was the flighty sort of fellow you can't count on. It's a pity though that he had to come to a bad end... but it couldn't be otherwise, as you can see. I've always said that nothing good will come of those who forget old friends." At that he turned away to conceal his agitation and began pacing up and down the courtyard beside his carriage, pretending to examine the wheels, while the tears kept filling up his eyes.

"Maksim Maksimich," said I, walking up to him. "What were the papers Pechorin left with you?"

"The Lord knows! Some notes or other. . ."

"What do you intend to do with them?"

"Eh? I'll have them made into cartridges."

"You'd do better to give them to me."

He looked at me in amazement, muttered something under his breath and began to rummage through his suitcase. He took out one notebook and threw it contemptuously on the ground. The second, the third and the tenth all shared the fate of the first. There was something childish about the old man's resentment, and I was both amused and sorry for him.

"That's the lot," he said. "I congratulate you on your find."

"And I may do whatever I want with them?"

"Print them in the newspapers if you like, what do I care? Yes, indeed, am I a friend of his or a relative? True, we shared the same roof for a long time, but then I've lived with all sorts of people."

I took the papers and carried them off before the captain could change his mind. Soon we were told that the "occasional" would set out in an hour, and I gave orders to harness the horses. The captain came into my room as I was putting on my hat. He showed no sign of preparing for the journey. There was a strained coldness about him.

"Aren't you coming, Maksim Maksimich?"

"No."

"Why?"

"I haven't seen the commandant, and I have to deliver some government property to him."

"But didn't you go to see him?"

"Yes, of course," he stammered, "but he wasn't in and I didn't wait for him."

I understood what he meant. For the first time in his life, perhaps, the poor old man had neglected his duties for his personal convenience, to put it in official language, and this had been his reward!

"I'm very sorry, Maksim Maksimich," I said, "very sorry indeed, that we have to part so soon."

"How can we ignorant old fogies keep up with you haughty young men of the world? Here, with Circassian bullets flying about, you put up with us somehow... but if we chanced to meet later on you'd be ashamed to shake hands with the likes of us."

Читать дальше

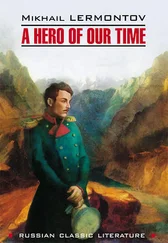

![Михаил Лермонтов - A Hero of Our Time [New Translation]](/books/27671/mihail-lermontov-a-hero-of-our-time-new-translati-thumb.webp)