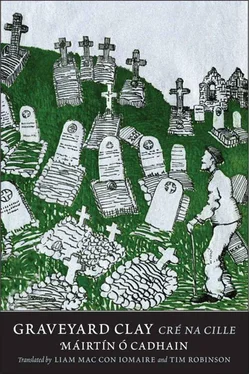

RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta marked the sixtieth anniversary of Cré na Cille ’s appearance in print on 10 March 2010 with a sixty-minute radio documentary, Cré na Cille: Seasca Bliain os cionn Talún (sixty years above ground). This documentary, produced by Dónall Ó Braonáin, contains a useful synopsis of critical thinking on Ó Cadhain’s masterpiece and features contributions from Éamon Ó Ciosáin, Lochlainn Ó Tuairisg, Róisín Ní Ghairbhí, Louis de Paor, Gearóid Denvir, Alan Titley, Máire Ní Annracháin, and Cathal Ó Háinle. Another television film is worthy of particular note: Ó Cadhain ar an gCnocán Glas , which was produced and directed by Aindreas Ó Gallchóir (1929–2011) for RTÉ and broadcast on 13 February 1967. The then single-channel national television service was a relatively recent arrival (1962) to the Irish media scene, but many interesting literary documentary features were produced in the initial years of RTÉ television. Ó Cadhain ar an gCnocán Glas is a short but arresting autobiographical portrait and features a visit by Máirtín Ó Cadhain to his native village and ancestral home approximately one mile west of Spiddal. Through a series of direct confessional pieces to the camera, short reflective voice-overs and unscripted, informal conversations with his neighbours, Ó Cadhain’s playful and humorous personality reveals itself in the course of twenty-four minutes. The film was shot in black and white by Will Warham, edited by Merritt Butler, remastered and rereleased by RTÉ Archives, and published in a DVD set with Rí an Fhocail by Cló Iar-Chonnacht in 2007.

Focal Scoir /Final Word

The last word is best left to Máirtín Ó Cadhain himself. In a contribution to a symposium entitled “Literature in the Celtic Countries” in Cardiff in 1969, he told of coming into the Hogan Stand in Croke Park on All Ireland Day as the teams waited for the parade:

In passing, a man whom I did not know, said in the Queen’s English and pointing his finger at me, “There goes Cré na Cille .” In pre-television days few writers of English, if any, would have been so recognised. The man said it as if he had a claim on me, as if he felt I was one of his own, one he could kick around, as the burly Kerry full-back was kicking the football about at the same moment. And of course I was. Whether he spoke Irish or not, he felt I belonged to him in a special way, one who was beyond yea or nay his own. This is worth more than all the money and all the sales in the world. It is recognition … 56

Liam Mac Con Iomaire

ON TRANSLATING CRÉ NA CILLE

More talked about than read, for over threescore years Cré na Cille has been the buried treasure of modern Irish-language literature. Our aim in this translation is modest: to give the Anglophone reader the most accurate answer we can provide to the question, What is in this book? There is ample space in the shadow of Ó Cadhain for “versions,” subjective interpretations, radical transpositions into other settings and periods, even parodies; these things will follow. But, be faithful to Ó Cadhain has been our first commandment. This of course involves much more than word-for-word equivalence. In English the words are often lacking, Ó Cadhain being a word addict with access to a world that feasted upon its verbal riches, having little else. So it has often been necessary to jump out of the footsteps of the Irish text, run round it, and fall in with it again at the next corner.

A word on our working method. My Irish was picked up in Aran and south Conamara in the middle of a busy life, when I was exploring and mapping those intricate landscapes; it was serviceable enough then for discussing states of the tide, the gossip of the townlands, and the promise of the potato crop, but nowadays it is hardly fit for public use. Hence the basis of our translation was produced by Liam, and then the two of us worked through it repeatedly, almost phrase by phrase. In searching for the English words that would most clearly convey Ó Cadhain’s meaning, we have tried to avoid flattening out his extravagances, his anarchic wit, his otherness, his sheer strangeness. At an early stage parts of our text were circulated among anonymous readers by the publisher, eliciting a wide range of comments and suggestions, for all of which we are grateful, and some of which we have adopted, while feeling that their mutual contradictoriness left us free to follow our own lights, which implies that the shortcomings of the present version are entirely our own. Nevertheless we gratefully acknowledge the guidance of Éamon Ó Ciosáin and Gearóid Ó Crualaoich in negotiating some particularly tangled corners of Ó Cadhain’s thorny masterpiece, and of Pádraig Ó Snodaigh, who read through and helpfully commented on our translation.

One of the most frequent and urgent recommendations made to us concerned what is almost an established practice with weighty precedents, of leaving personal names and placenames untranslated, in order to root the text in its original setting in time and space. There is point to this; one doesn’t want to be pretending that Caitríona and her neighbours are buried in some present-day English graveyard. But there are other ways of preserving a whiff of the book’s setting, its irreducible foreignness, across the linguistic gulf. The countless mentions in Cré na Cille of little stony fields, seaweed harvesting, holy wells, and so on, and the occasional references to a motor car, a movie, a woman in trousers, sufficiently locate it in a rural seaside community at a period when its folk ways are being invaded by modernity. (Also, if precedent is to be given weight in this debate, there is on the side of translation the splendid example of Brightcity, Eoghan Ó Tuairisc’s version of Ó Cadhain’s name for the city of Galway, in “An Bóthar go dtí an Ghealchathair.”) The point is this. Placenames are semantically two-pronged. The placename on the one hand denotes a location, and on the other bears a load of connotations with it, including the associations that make a place, an element of a life-world, out of the bare location. But the places mentioned in Cré na Cille are fictional, which complicates the relationship between denotation and connotation; the only existence of these places is in the text, and all we know of them is what the text tells us, which it does partly through the placename itself. What is denoted is constituted by the connotations. Of Lake Wood, all we know is that there is or was a lake and a wood; but given the general setting we can imagine the place. Pasture Glen, the Common Field, Mangy Field, Flagstone Height, Donagh’s Village, West Headland, Colm’s Cove, Woody Hillside, the Deep Hollow, Roadside Field, the Hill Field, and so on, and so on — cumulatively these names paint a picture of a small-scale, well-worked countryside intimately known to its inhabitants. To replace them all with strings of letters the non-Irish-speaking reader will not even be able to pronounce would entail a tremendous loss of texture, of precious discriminations, of meaning. Of course there are difficult choices to be made in translating some of them. To avoid a touch of the English suburban estate we have rendered Lake Wood as Wood of the Lake, and Pasture Glen as Glen of the Pasture, for instance. Also, it’s not possible to give the full sense of tamhnach in one or two English words — but such obstacles are just the usual ones that make translation a joy frustrated.

A similar argument applies to personal names, but in the present text it is not so pressing, since the English or anglicised equivalents of most of them — Cáit, Bríd, and the like — are obvious anyway. A few that are just English names spelled in the Irish phonetic system, such as Jeaic, we have let revert to their English forms. However, we found it necessary to translate nicknames, as they are indicative of status, appearance, ancestry, or the community’s attitude towards the person named. So we have “Siúán the Shop” and “Máirtín Pockface,” for example. As with placename elements there are some puzzles, of course: what exactly is implied by the nickname of Tomás Taobh Istigh we think we know, but the ambiguity of Jeaic na Scolóige’s name is not just in our minds but commented on (unrevealingly) by other characters in the book.

Читать дальше