— But I did …

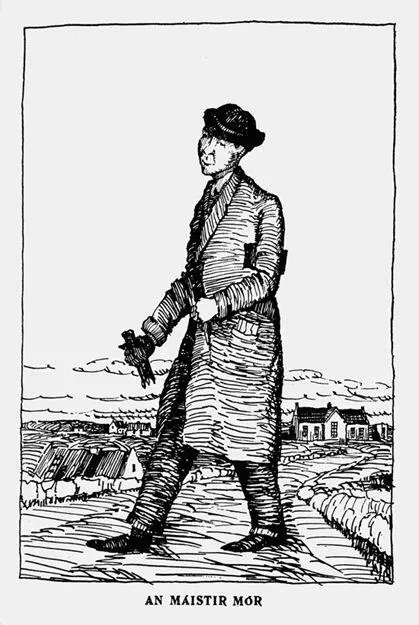

— You did, and so did I. Hold on. He was the biggest miser who ever wore clothes. He was so shrewd he could herd mice at a crossroads, as they say. The only wild deed he ever did was that trip to London when the teachers got the rise …

— That was the time he was in the nightclub.

— It was. He spent the rest of his life telling me about it, and warning me to keep my mouth shut about it. “If the priest or the Schoolmistress heard about it!” he would say …

Then he married her: the Schoolmistress.

“Maybe,” said I to myself, “I’ll succeed in locating some generosity in him now. The Schoolmistress would be a great backing to me if I could only cajole her. And it is possible to cajole her.” There isn’t a woman born who hasn’t that kernel of vanity, if one can only uncover it. I didn’t spend time selling insurance without knowing that.

— I know it too. It’s easier to sell to women than to men if you have your wits about you …

— I’d have to allow some time for the novelty of the marriage to wear off a little. But I couldn’t leave it too long either, because he might not be so amenable to his wife’s advice if he was beginning to lose interest in her charms. Insurance people know these things …

— And booksellers too …

— I gave him three weeks … It was on a Sunday. Himself and herself were sitting out in front of the house after their lunch. “Here I come, you rascal,” says I … “By the bone marrow of my forebears I’ll do business today! … You have the week’s work schedule prepared by now, and the notes you’re forever talking about. You’re stuffed with food, and if the wife is at all favourable it will be easier to play on you than another time …”

We had a bit of chat about the affairs of the Realm. I said I was in a hurry. “Sundays and Mondays are all the same to me,” said I. “Always prowling, ‘seeking whom I may devour.’ Now that you’re married, Master, the Mistress should make you take out a policy on your life. You’re more valuable now than you were before. You have the responsibilities of a spouse … I’m of the opinion,” says I to the wife, “that he doesn’t love you at all, but you serve his purpose, and if you die he’ll take another one.”

The two of them laughed heartily. “And,” said I, “as an insurance man I have to tell you that if he dies there is no provision made for you. If I had a ‘gilt-edged security’ like you …”

She turned a little sulky: “Yes,” she said to the Master, half in jest and half in earnest, “if anything should happen to you, the Lord between us and all harm …”

“What could happen to me?” says he, in a disgruntled voice.

“Accidents are as common as air,” says I, “it’s the duty of the insurance man always to say that.”

“Exactly,” says she. “I hope nothing will happen. May God forbid! If anything did happen to you, I wouldn’t survive without you. But, the Lord between us and all harm, if you should die and if I didn’t die at the same time … what would become of me? It’s your duty …”

And, believe it or not, didn’t he take out a life insurance policy! One thousand five hundred pounds. He had only paid four or five instalments, I think — big instalments too. She made him take out another two hundred and fifty at the time of the last instalment. “He won’t last long,” says she with a smile, and she gave me a wink.

She was right. It wasn’t long before he wasted away …

I’ll tell you about another big coup I had. It wasn’t half as good as the one with the Big Master …

— You got one over on the Big Master just as Nell Pháidín did on Caitríona about Jack the Scológ …

— Ababúna! I’ll explode! I’ll explode! I’ll ex …

4

Hey, Muraed! Hey, Muraed! … Can you hear me? … They were burying Seáinín Liam on top of me. Indeed they were, Muraed … Oh, have a bit of sense, Muraed! Why would I allow him into the same grave as me? I never had to pick and sell periwinkles. Didn’t he and his people live on periwinkles, and I’d remind him of that too. Even in the short time I spent talking to him he nearly drove me mad going on about his old heart … It’s true for you, Muraed. If I had a cross on my grave it would be easily recognised. But I’ll have a cross soon now, Muraed. Seáinín Liam told me. A cross of Island limestone like the one over Peadar the Pub … My son’s wife, is it? Seáinín Liam said she’d be here on her next childbirth for certain …

Do you remember our Pádraig’s eldest girl, Muraed? Yes. Máirín … That’s right, Muraed. She’d be fourteen now … You’re right. She was only a plump little thing when you died. She’s in college now. Seáinín Liam told me … to become a schoolmistress! What else! You don’t think she’d be sent to college to learn how to boil potatoes and mackerel now, or make beds or scrub the floor? That old scrubber of a mother of hers could do with that, if there was such a college …

Máirín was always fond of school. She has a great head on her for a child of her age. She was away ahead of the Schoolmistress — the Big Master’s wife — before the Master died. There’s nobody in the school who’s any way near her, Seáinín Liam tells me.

“She’s extremely advanced in learning,” he says. “She’ll be qualified a year before everybody else.”

Upon my word, he did, Muraed … Now Muraed, there’s no need for talk like that. It’s not a wonder at all. Why do you say it’s a wonder, Muraed? Our people had brains and intellect, even if I say so myself …

— … But that’s not what I asked you, Seáinín.

— Ah, Master, the heart! The heart, God help us! I’d been for the pension. Devil a thing I felt … Now Master, don’t be so irritable. I can’t help it. I fetched a creel of potatoes. When I was easing it off me … But Master, I’m not saying a word but the truth. Of course I know damn all about it, Master, but what I heard people saying. I had more to worry about, unfortunately. The creel came down lopsided. I gave … What were the people saying, Master? Our people had no time for saying anything, Master, or listening to anything. We were building a new stable for the colt …

What were the people saying, Master? You know yourself, Master — a man like you with so much education, God bless you — that there are some people who can’t live without gossiping. But a person who has a weak heart … Amn’t I telling you what they’re saying, Master, if only you’d have a bit of patience and not be so ratty with me. I wouldn’t mind, but the weather was great for a long time while we were building the stable … The people, Master? They’re saying more than their prayers, Master. But a person who has a weak heart, God help us …

The Schoolmistress, is it? I never saw her looking better, Master, God bless her! ’Tis younger she’s getting, so it is. She must have a great heart … People used to be talking indeed, Master. There’s no denying that. But faith, myself and the young fellow were busy with the stable … Don’t be so ratty with me, Master dear. Of course, everybody in the country was saying Billyboy the Post was never out of your house.

It was a fine big colt, Master … What’s the use of being so ratty with me, Master. There’s damn all I can do about whatever happens to the whole lot of you. I had more to worry about, God help … He spends time in the house, is it? On my soul, he does indeed, Master. I wouldn’t mind that, but in the school as well. He calls into the school every day and gives the letters to the children, and himself and the Schoolmistress go out into the hall for a chat. Arrah, God bless your innocence, Master. You don’t know the half of it. But I had more to worry about. There wasn’t a puff of breath left in my body. The heart …

Читать дальше