After several years during which her behaviour grows more seriously obsessive and paranoid, to the degree that she becomes incapable of making moral decisions, Roxana’s mental health finally gives way entirely. The thought of becoming a princess, she tells us, ‘turn’d my Head; and I was as truly craz’d and distracted for about a Fortnight, as most of the People in Bedlam , tho’ perhaps, not quite so far gone’ (p. 278). What has happened is that the continued melancholy has now turned into a ‘frenzy’ (more or less what we would call mania), a more serious form of delirium marked by a fever (melancholy was sometimes defined as a delirium without fever) and a raging of the blood which in turn has inflamed the animal spirits, producing acute mental distraction. This is precisely the condition Roxana describes when she speaks of the ‘violent Fermentation in my Blood’ and explains that ‘the very Motion which the steddy Contemplation of my fancy’d Greatness had put my Spirits into, had thrown me into a kind of Fever, and I scarce knew what I did’ (p. 279).

The final stage of her psychological breakdown occurs when Roxana realizes that her daughter, Susan, has been murdered by Amy. Having been abandoned years before by Roxana, and now desperately trying to re-establish contact with her mother, Susan is the incarnation of all Roxana’s years of guilt and fear. The superstructure of Roxana’s criminal prosperity has been raised on the foundation of the desertion, and later the denial, of her children. With the death of Susan, Roxana is released from the fear of exposure but the knowledge of her crime and her responsibility at the same time drives her mad, and her imagination is haunted by hallucinations of her dead daughter, with her throat slit, her brains dashed out, hanged, or drowned.

Of course Defoe employs the vocabulary of his own age to describe the symptoms of Roxana’s mental disease. In modern terms Roxana’s bouts of melancholy and of frenzy would probably be diagnosed as depression and mania, the alternating disturbed states of mind of the manic-depressive psychosis from which she suffers. Her condition is prolonged and made worse by the absence of a genuine friend and confidant, which modern psychiatry recognizes as a primary therapeutic factor, to whom she could turn for advice, and through whom she could regain contact with the real world outside herself. As a result she suffers increasingly and intensely from ‘a secret Hell within’, the slow-growing but relentless spiritual cancer which eats away at her emotional and mental health. Defoe understood the way in which repressed emotions bury themselves deep within the human personality until they grow claws and begin to dig their way out, and he knew, too, of the way in which ambition and pride corrupt and destroy the soul. His depiction of these terrible processes at work in Roxana is among the finest things he ever wrote.

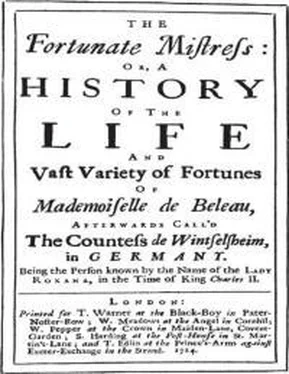

The dark ending of the novel, the story of her daughter Susan’s desperate attempt to force Roxana to acknowledge her and the fatal outcome of the girl’s pursuit of her mother, draws together the diverse strands of the book. Roxana’s exotic life – her wealth, foreign travel, splendid clothes and houses, lavish parties, and place at court – all rest upon the desertion of her five children and her willingness to become a whore. Moreover, she is from the beginning fully aware of her wickedness: ‘I was resolv’d to commit the Crime,’ she confesses, ‘knowing and owning it to be a Crime’ (p. 75). And at the height of her prosperity, while resolving to continue in her immoral way of living, she is forced to wonder, ‘ Why am I a Whore now ?’ (p. 244). The ending of the story draws the moral, and shows the link between Roxana’s crimes and the punishment which follows.

The symbol of Roxana’s immorality, and the link between her two lives, is the Turkish dress. Associated with the glamorous, dissolute, and aristocratic side of Roxana’s existence, the dress, which ‘wou’d not look modest’ in England (p. 291), and the ‘Turkish’ dance she performs while wearing it, cause her to be called ‘Roxana’, a name that suggests the courtesan, as Roxana knows when she refers to herself as ‘a meer Roxana’ (p. 223). As the perfect disguise, one in which even her husband ‘wou’d not know his Wife when he saw her’ (p. 291), the dress also reminds us of the deception and hypocrisy of the life of the kept mistress who ‘sculks about in Lodgings [and] is visited in the dark’ (p. 171). By the end of the novel it has become the symbol of all that is wrong in Roxana’s life, her need for concealment, her fear of exposure by her daughter, and her shameful past. And it is by means of the Turkish dress that Susan – once a servant in her own mother’s house at the time when Roxana danced, and Susan witnessed, her Turkish dance – is able to connect the wife of the Dutch merchant with the Lady Roxana, and to discover the identity of her mother.

As Roxana, driven distracted by the unrelenting pursuit of her daughter, twists and turns to avoid capture by the wretched and desperate Susan, the loyal but cold-blooded Amy finally murders the girl. Nothing else in Defoe is quite so shocking as this appalling resolution to the story. Yet it may be seen that the ending springs from the preceding pattern of crime with the logic of cause and effect. Roxana is able to achieve her remarkable success only at the high price of denying her children and suppressing her emotions. The terrible result is not only Roxana’s mental breakdown and insanity, but the great wrong that is done to her child. Susan, enduring the drudgery of a servant’s existence and witnessing her mother’s immoral life, is finally murdered by the woman who has usurped her station in life and taken her place in her mother’s affections. As long as Roxana is able to assist her children anonymously, hiding behind the screen of Amy, all is well. But Susan is the only child who demands the one thing that Roxana is unable to give her, the normal affection of a mother for her child. In his final novel Defoe, with a psychological insight for which he is seldom given credit, explored the way in which human beings may be torn apart and destroyed when their own desires and ambitions get at cross-purposes with one another. Roxana is such a woman, ruined because her immoderate vanity and ambition can only be satisfied at the expense of the love and trust which she desperately needs. Her life is her punishment, and her story Defoe’s expression of his tragic vision of the human lot.

In the preparation of this edition I have been assisted by the help kindly given me by the many individuals to whom I turned when the information I was seeking in books ran out. In particular, I am indebted to Paula Backschieder of the University of Rochester, New York (for advice about the chronology of Defoe); to Mary Boast of the Southwark Local Studies Library (for information about the pond at Camberwell); to David Higgs of the University of Toronto and to Roger Lockyer of Royal Holloway College, London (for information about French Protestantism); to Frank Melton of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (for information about Sir Robert Clayton); to V. Neressian of the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books, the British Library (for identifying the Armenian musical instruments on pp. 220–1); to Spiro Peterson of Miami University, Ohio (for identifying the quotation on p. 244); to H. C. Porter of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (for the identification of ‘the Indian King at Virginia’, p. 290); to Julian Raby of the Oriental Institute, Oxford (for information about Roxana’s Tyhiaai) ; to Jennifer M. Scarse of the Royal Scottish Museum (for information about eighteenth century Turkish costume); to G. A. Starr of the University of California, Berkeley (for information about the quotation on p. 104); and to Raymond Stephanson of the University of Saskatchewan, who generously allowed me to read his paper on ‘The Historical Foundation of Mental Illness in Roxana ’ before publication. I am also indebted to members of my family; to my brothers William, a computer scientist, and Edwin, an economist, for advice about Sir Robert Clayton’s ‘Scheme of Frugality’, and, above all, to my late father, whose scholarly acumen was invaluable to me in preparing the text. Finally, I wish to thank the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, which provided financial support for three months’ research in London.

Читать дальше