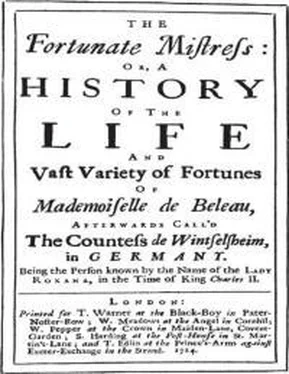

In a similar, though rather more complex, way the novel’s double time-scheme draws attention to the moral decline of the age of George I. Ostensibly the novel is set in the reign of Charles II, as the title-page and a number of allusions in the novel suggest. Roxana, for example, employs as her financial adviser Sir Robert Clayton, who rose to prominence in the reign of Charles II and died in 1707, and she bears a resemblance to Nell Gwynn, Charles’s mistress, who once memorably, like Roxana, referred to herself as a ‘Protestant Whore’ (p. 105). Above all Defoe evokes the atmosphere of the Restoration court with its balls and masquerades and pretty actresses who caught the eyes of men of quality and were asked to court.

But in the novel’s opening pages Roxana tells us that she was almost ten years old in 1683 when she was brought to England by her parents. Born in 1673, Roxana would have been twelve in the year of Charles II’s death, and it is clear from many other references to time in the novel [1] See Paul Alkon, Defoe and Fictional Time (University of Georgia Press, 1979), pp. 53–8, and my Defoe’s Art of Fiction (University of Toronto Press, 1979), pp. 126–7.

that when Roxana is living in London, giving fashionable masquerade parties, and eventually becoming the mistress of the King, that the time is just after 1715, and the court that of George I. Of course Defoe is satirizing the age in which he was living by drawing a moral comparison between the reign of George I and the reign of Charles II. Several times elsewhere in his writings Defoe contrasts the ‘vile debauch’d Taste of King Charles the Second’s Reign’ [2] See The Weekly Journal (5 April 1719), reprinted in William Lee, Daniel Defoe: His Life and Recently Discovered Writings (1869), II, 32; and The Fears of the Pretender Turn’d into the Fears of Debauchery (1715), esp. pp. 31–4.

with the moral probity of the courts of King William, one of Defoe’s heroes, and of Queen Anne. Then shortly after the arrival of George I in England, as it seemed to Defoe, many of the morally deplorable practices of Charles II’s time were revived. Both the King and the Prince of Wales kept mistresses, the theatres flourished, the extravagant new Italian opera came into vogue, and above all, the masquerades were revived and given royal support.

It is hard now to understand the opposition the masquerades aroused, but with the opportunity they provided (since everyone was disguised) for the indiscriminate mixing of social classes in public and semi-public places, and the sexual licence that was consequently thought to ensue, the masquerades were seen by moral reformers as both symptom and cause of a national moral decline. [3] Early in January 1724, only six weeks before Roxana was published, the Bishop of London preached a sermon against masquerades, which brought forth a retort in verse from John James Heidegger, their chief organizer and, by royal appointment, Master of the Revels.

By setting his novel in the reigns of George I and Charles II at the same time , and by placing Roxana in the heart of fashionable West End court life with its gambling parties and masquerades and by making her the King’s mistress, Defoe suggests that Roxana’s story of moral decay goes beyond the individual to include, and condemn, the world she inhabits.

The two modes of existence of Roxana’s life – ‘The opposite Circumstances of a Wife and a Whore ’ as she neatly puts it – are the subject of the lengthy debate at the heart of the moral comment of the novel. When she rejects the Dutch merchant’s attractive offer of marriage, Roxana argues that a woman of independent means has nothing to gain and everything to lose in marriage. She loses her freedom, becomes an ‘ Upper-Servant ’ or housekeeper in her own family, and gives up her fortune to the control of her husband. Roxana correctly understands the legal status of women in her day. An unmarried woman who had come of age enjoyed essentially the same legal rights as a man, that is, the right to own and dispose of property, to make contracts, and to enter into litigation. When she married, however, she lost these rights, since at law she became one person with her husband, in whom the legal existence of the couple was solely vested. Like a number of outspoken feminists of her day, [4] e.g., Mary Astell, Aphra Behn, Lady Chudleigh, and Hannah Wooley.

Roxana argues ‘That the very Nature of the Marriage-Contract was, in short, nothing but giving up Liberty, Estate, Authority, and every-thing, to the Man, and the Woman was indeed, a meer Woman ever after, that is to say, a Slave’ (p. 187).

Our sympathy for Roxana is aroused not only by the force and skill of her argument, but also by the melancholy circumstances of her early life. At the age of fifteen Roxana became the victim of a disastrous marriage arranged for her by her father when she was still sufficiently impressionable to be captivated by her husband’s good looks and dancing ability. But she then watches helplessly as her fool of a husband squanders his own money and her dowry, until finally he leaves her, penniless and with five children on her hands. Elsewhere in his writings [5] See Conjugal Lewdness (1727), especially pp. 101–3.

Defoe inveighs against ‘prudential’ marriages (arranged for financial reasons, often without adequate time for consideration by the marriage partners) – he calls such matches ‘matrimonial whoredom’ – and there is little doubt that we are meant to see Roxana as a woman whose negative opinions about marriage are initially determined by circumstances over which she has little control. As a beautiful and engaging young woman, however, she is not long in discovering that, by becoming the mistress of her landlord, a wealthy jeweller, she can live far better than ever she had as a married woman, and her subsequent rise to spectacular riches confirms her notions about the advantages of a mistress over those of a wife. Morally the transition from one mode of existence to the other is reprehensible, as Roxana is painfully aware, but the ease of the transition and the extenuating circumstances of her first marriage permit a considerable degree of sympathy with the heroine. When, by the middle of the novel, Roxana argues her case for ‘the Dignity of Female Liberty’ (p. 269), it is against a background of marital wretchedness and subsequent happiness (albeit broken occasionally by bouts of guilty conscience) that does much to explain the vehemence of her argument and helps us to understand it. Defoe, with his usual capacity for presenting an argument forcibly even when he disagrees with it, makes as strong a case for Roxana’s position as he can.

Defoe was sensitive to the disadvantages women suffered in a society that denied them sexual, moral, educational, and legal equality with men, and in a number of works on marriage and the family [6] The Family Instructor, In Three Parts (1715); The Family Instructor, In Two Parts (1718); Religious Courtship (1722); The Great Law of Subordination Consider’d (1724); Conjugal Lewdness (1727); A New Family Instructor (1727).

he took an active part in a contemporary public argument about marriage and the role of marriage partners, reserving his greatest sympathy for daughters forced into distasteful alliances and for wronged wives. Defoe was in the forefront of those who argued for greater autonomy, particularly for women, and for a more equal relationship between marriage partners. Nonetheless, for all his sympathy with the position of women, Defoe makes it clear that there is no question but that Roxana, in arguing against marriage, is deeply and disturbingly wrong. The case against her is made by the Dutch merchant, whose views on marriage are Defoe’s own. He points out that while it is true that a married woman is subject to her husband, on the other hand, he has all the care and responsibility of earning a living, while she enjoys the benefits of his labour. But such a quid pro quo does not satisfy Roxana, who claims an absolute equality with men. This assertion, undoubtedly shocking to many of Defoe’s contemporaries, was ahead of its time, but when Roxana goes further, even to claiming the liberty of entertaining ‘a Man, as a Man does a Mistress’ (p. 188), contemporary readers would have had no doubt that her claim to an equality of sexual immorality with men was indefensible. Defoe intends us to see the unconventionality of Roxana’s stand.

Читать дальше