Марк Твен - Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Марк Твен - Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Москва, Год выпуска: 2017, ISBN: 2017, Издательство: АСТ, Жанр: Классическая проза, foreign_language, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

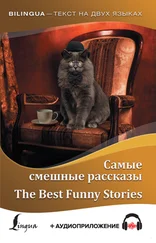

- Название:Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]

- Автор:

- Издательство:АСТ

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- Город:Москва

- ISBN:978-5-17-104431-2

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories] — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He returned to business, sprinkled me all over, legs and all, greased my hair in spite of my protest against it. He combed my scant eyebrows and defiled them with pomade. Right then I heard the whistles blow for noon, and knew I was five minutes too late for the train. Then he snatched away the towel, brushed it lightly about my face, passed his comb through my eyebrows once more, and gaily sang out “Next!”

This barber fell down and died of apoplexy two hours later. I am waiting over a day for my revenge — I am going to his funeral.

The Danger of Lying in Bed

The man in the ticket-office said:

“Would you like to have an accident insurance ticket, also?”

“No,” I said, after studying the matter over a little. “No, I believe not; I am going to be traveling by rail all day today. However, tomorrow I don’t travel. Give me one for tomorrow.”

The man looked puzzled. He said:

“But it is for accident insurance, and if you are going to travel by rail-”

“If I am going to travel by rail I won’t need it. Lying at home in bed is the thing _I — am afraid of.”

Last year I traveled twenty thousand miles, almost entirely by rail; the year before, I traveled over twenty-five thousand miles, half by sea and half by train; and the year before that I traveled ten thousand miles exclusively by rail. I may say I have traveled sixty thousand miles during the three years I have mentioned. AND NEVER AN ACCIDENT.

For quite a long time I said to myself every morning: “Now I have escaped thus far, and so the chances are just that much increased that I will catch it this time. I will buy an accident ticket.” And certainly everything went perfectly well. I bought accident tickets that were good for a month. I said to myself, “A man CAN’T buy thirty useless tickets.”

But I was mistaken. There was never a prize in the lot. I could read of railway accidents every day; but somehow they never came my way. I found I had spent a good deal of money in the accident business, and had nothing to show for it. I began to hunt around for somebody that had won in this lottery. I found plenty of people who had invested, but not an individual that had ever had an accident or made a cent. THE PERIL LAY NOT IN TRAVELING, BUT IN STAYING AT HOME.

I hunted up statistics, and was amazed to find that less than THREE HUNDRED people had really lost their lives by railroad disasters in the preceding twelve months. The Erie road was the most murderous in the list. It had killed forty-six — or twenty-six, I do not exactly remember which, but I know the number was double that of any other road. But the Erie was an immensely long road, and did more business than any other line in the country.

By further figuring, it appeared that between New York and Rochester the Erie ran eight passenger-trains each way every day — 16 altogether; and carried a daily average of 6,000 persons. That is about a million in six months — the population of New York City. Well, the Erie kills from 13 to 23 persons of ITS million in six months. At the same time 13,000 of New York’s million die in their beds! My hair stood on end. “This is terrible!” I said. “The danger isn’t in traveling by rail, but in trusting to those deadly beds. I will never sleep in a bed again.”

I had figured further that an average of 2,500 passengers a day for each road in the country would be almost correct. There are 846 railway lines in our country, and 846 times 2,500 are 2,115,000. [11] … 846 times 2,500 are 2,115,000 — …846 умножить на 2 500 будет 2 115 000.

So the railways of America move more than two millions of people every day; six hundred and fifty millions of people a year, without counting the Sundays. They do that, too — there is no question about it; though where they get the raw material is clear beyond the jurisdiction of my arithmetic, as I find that there are not that many people in the United States. They must use some of the same people over again, likely.

There are 500 deaths a week in New York and 60 deaths a week in San Francisco. That is 3,120 deaths a year in San Francisco, and eight times as many in New York — say about 25,000 or 26,000. The health of the two places is the same. So we will let it stand as a fair presumption that this will hold good all over the country, and that 25,000 out of every million of people we have must die every year. That is one-fortieth of our total population. One million of us, then, die every year. Out of this million ten or twelve thousand are stabbed, shot, drowned, hanged, poisoned, or meet a similarly violent death in some other popular way, such as perishing by kerosene-lamp, getting buried in coal-mines, falling off house-tops, taking patent medicines, or committing suicide in other forms. The Erie railroad kills 23 to 46; the other 845 railroads kill an average of one-third of a man each; and the rest of that million — 987,631 corpses — die naturally in their beds!

You will excuse me from taking any more chances on those beds. The railroads are good enough for me.

And my advice to all people is, Don’t stay at home any more than you can help; but when you have GOT to stay at home a while, buy a package of those insurance tickets and sit up nights. You cannot be too cautious.

The moral of this composition is, that people grumble more than is fair about railroad management in the United States. When we consider that every day and night of the year full fourteen thousand railway-trains of various kinds go over the land, the marvel is, NOT that they kill three hundred human beings a year, but that they do not kill nine hundred thousand!

Speech on the Weather

I believe that the Maker who made us all makes everything in New England but the weather. I don’t know who makes that, but I think it must be raw apprentices in the weather-clerk’s factory who experiment and learn how, in New England, and then are either promoted to make weather for other countries or go elsewhere. There is a unique variety about the New England weather that makes any stranger admire — and regret it. The weather is always doing something there; always getting up new designs and trying them on the people to see how they will go.

But it gets through more business in spring than in any other season. In spring I have counted one hundred and thirty-six different kinds of weather inside of four-and-twenty hours. It was I that made the fortune of that man that had that marvelous collection of weather on one exhibition, that so amazed the foreigners. One of them was going to travel all over the world and see all the kinds of climates. I said, “Don’t do it; just come to New England on a spring day.” I told him what he would be pleased with style, variety, and quantity. Well, he came and he made his collection in four days. As to variety, why, he confessed that he got hundreds of kinds of weather that he had never heard of before. And as to quantity, he not only had weather enough, but weather to hire out; weather to sell; to deposit; weather to invest; weather to give to the poor.

The people of New England are by nature patient, but there are some things which they will not stand. Every year they kill a lot of poets for writing about “Beautiful Spring.” These are generally casual visitors, who bring their notions of spring from somewhere else, and cannot, of course, know how the natives feel about spring.

The weather forecaster Old Probabilities has a mighty reputation for accurate prophecy, and thoroughly well deserves it. You take up the paper and observe how confidently he checks off what today’s weather is going to be on the Pacific, down South, in the Middle States, in the Wisconsin region till he gets to New England. He doesn’t know what the weather is going to be in New England. Well, by and by he gets out something about like this: Probable northeast to southwest winds, varying to the southward and westward and eastward, high and low barometer swapping around from place to place; probable areas of rain, snow, hail, and drought, succeeded or preceded by earthquakes, with thunder and lightning. Then he writes down this postscript, to cover accidents: “But it is possible that the program may be wholly changed in the meantime.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

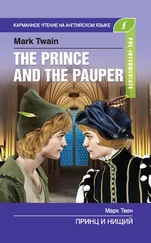

Похожие книги на «Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories]» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Марк Твен Смешные рассказы [The Funny Stories] обложка книги](/books/29189/mark-tven-smeshnye-rasskazy-the-funny-stories-cover.webp)