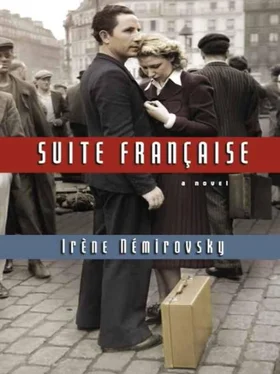

"What's happened?" she asked.

"I wonder…" replied Madame Angellier, clasping her hands together so tightly that Lucile could see her nails turning white, "I wonder why you ever married Gaston?"

There is nothing more consistent in people than their way of expressing anger. Madame Angellier's way was normally as devious and subtle as the hissing of a serpent; Lucile had never endured such an abrupt, harsh attack. She was less indignant than upset; suddenly she realised how much her mother-in-law must be suffering. She remembered their melancholy, affectionate and deceitful black cat who would purr, then slyly lash out with her claws. Once she even went for the cook's eyes, nearly blinding her. That was the day her litter of kittens had been drowned. After that she'd disappeared.

"What have I done?" Lucile asked quietly.

"How could you, here, in his house, outside his windows, with him gone, a prisoner, ill perhaps, abused by these brutes, how could you smile at a German, speak with such familiarity to a German? It's inconceivable!"

"He asked my permission to go into the garden to pick some strawberries. I couldn't exactly refuse. You're forgetting he's in charge here now, unfortunately… He's being polite, but he could take whatever he wants, go wherever he pleases and even throw us out into the street. He wears kid gloves to claim his rights as a conqueror. I can't hold that against him. I think he's right. We're not on a battlefield. We can keep all our feelings deep inside. Superficially at least, why not be polite and considerate? There's something inhuman about our situation. Why make it worse? It isn't… it isn't reasonable, Mother." Lucile spoke so passionately that she surprised even herself.

"Reasonable!" exclaimed Madame Angellier. "But my poor girl, that word alone proves you don't love your husband, that you've never loved him and you don't even miss him. Do you think that I try to be reasonable? I can't bear the sight of that officer. I want to rip his eyes out. I want to see him dead. It may not be fair, or humane, or Christian, but I am a mother. Being without my son is torture. I hate the people who have taken him away from me, and if you were a real wife, you wouldn't have been able to bear that German being near you. You wouldn't have been afraid of appearing uncouth, rude, or ridiculous. You would have simply got up and, with or without an excuse, walked away. My God! That uniform, those boots, that blond hair, that voice, and that look of good health and contentment, while my poor son…"

She stopped and began to cry.

"Come on now, Mother…"

But Madame Angellier became even more enraged. "I wonder why you ever married him!" she exclaimed again. "For his money, for his land no doubt, honestly…"

"That's not true. You know very well it's not true. I got married because I was a little goose, because Papa said, 'He's a good man. He'll make you happy.' I never imagined he'd start being unfaithful to me with a hatmaker from Dijon as soon as we got married!"

"What?… What on earth are you talking about?"

"I'm talking about my marriage," Lucile said bitterly. "At this very moment a woman in Dijon is knitting Gaston a sweater, making him sweetmeats, sending him packages and probably writing 'My poor sweetheart, I'm so lonely without you tonight, in our great big bed.'"

"A woman who loves him," muttered Madame Angellier, her lips becoming as thin and sharp as a razor, and turning the colour of faded hydrangea.

"At this very moment," Lucile thought to herself, "she would cheerfully kick me out and have the hatmaker here instead," and with the treachery present in even the best of women, she insinuated, "It's true he loves her… a lot… You should see his chequebook. I found it in his desk when he left."

"He's spending money on her?" cried Madame Angellier, horrified.

"Yes; and I couldn't care less."

There was a long silence. They could hear the familiar sounds of evening: the neighbour's radio sending out a series of piercing, plaintive, droning notes, like Arab music or the screeching of crickets (it was the BBC of London distorted by interference), the mysterious murmuring of some stream hidden in the countryside, the insistent croak of a thirsty frog praying for rain. In the room, the copper lamp that hung from the ceiling-rubbed and polished by so many generations that it had lost its pink glow and was now the pale, yellow colour of a crescent moon-shone down on the two women sitting at the table. Lucile felt sad and remorseful.

"What's wrong with me?" she thought. "I should have just let her criticise me and said nothing. Now she'll get even more upset. She'll want to make excuses for her son, patch things up between us. God, how tedious!"

Madame Angellier didn't say a word for the rest of the meal. After dinner they went into the sitting room, where the cook announced the Viscountess de Montmort. This lady, naturally, did not associate with the middle-class people of the village; she wouldn't invite them into her home any more than she would her farmworkers. When she needed a favour, however, she would come to their homes to make the request with the simplicity, ingenuousness and innocent superiority of the "well-bred." The villagers didn't realise that when she dropped by, dressed like a chambermaid, wearing a little red felt hat with a pheasant feather that had seen better days, she was demonstrating the profound scorn she felt towards them even more clearly than if she had stood on ceremony: after all, they didn't get dressed up to go to a neighbouring farm to ask for a glass of milk. Her deception worked. "She's not stuck-up," they all thought when they met her. Nevertheless, they treated her with extraordinary condescension-and they were just as unaware of it as the Viscountess was of her feigned humility.

Madame de Montfort strode into the Angelliers' sitting room; she greeted them cordially; she didn't apologise for coming so late; she picked up Lucile's book and read the title out loud: Connaissance de l'Est by Claudel.

"Very good indeed," she said to Lucile with an encouraging smile, as if she were congratulating one of the schoolgirls for reading the History of France without being forced to. "You like reading serious books, very good indeed."

She knelt down to pick up the ball of wool the elder Madame Angellier had just dropped.

"You see," the Viscountess seemed to say, "I've been brought up to respect my elders; their background, their education, their wealth mean nothing to me; I see only their white hair."

Meanwhile, Madame Angellier, with an icy nod of the head, barely moving her lips, invited the Viscountess to sit down. Everything inside her seemed silently to scream, "If you think I'm going to be flattered by your visit you're mistaken. My great-great-grandfather might have been one of the Viscount de Montmort's farmers, but that's ancient history and no one even knows about it, whereas everyone knows the exact number of hectares of land your dead father-in-law sold to my late husband when he needed money; what's more, your husband managed to come back from the war, while my son is a prisoner. I am a suffering mother and you should be showing respect to me." To the Viscountess's questions she replied quietly that she was in good health and had recently heard from her son.

"You have no hope?" asked the Viscountess, meaning "hope that he'll soon come back home."

Madame Angellier shook her head and raised her eyes to heaven.

"It's so sad," said the Viscountess and added, "We're going through such hard times."

She said "we" out of that sense of propriety which makes us pretend we share other people's misfortunes when we're with them (although egotism invariably distorts our best intentions so that in all innocence we say to someone dying of tuberculosis, "I do feel for you, I do understand, I've had a cold I can't shake off for three weeks now").

Читать дальше

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)