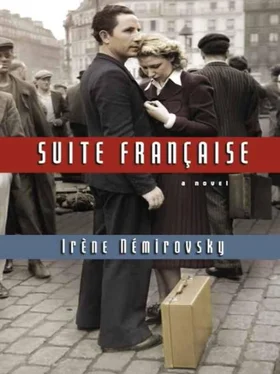

"What?"

"Benoît, I just remembered. You have to hide your shotgun. Did you read the posters in town?"

"Yes," he said sarcastically. "Verboten. Verboten. Death. That's all they know how to say, the bastards."

"Where are you going to hide it?"

"Forget it. It's fine where it is."

"Benoît, don't be stubborn! It's serious. You know how many people have been shot for not turning in their weapons."

"You want me to give them my gun? Only chickens do that! I'm not scared of them. You want to know how I got away last summer? I killed two of them. They didn't know what hit them! And I'll kill some more," he said furiously, shaking his fist in the dark at the German upstairs.

"I'm not saying you should hand it in, just hide it, bury it… There are plenty of good hiding places."

"Can't."

"Why not?"

"I've got to have it to hand. You think I'm going to let the foxes near us-or all the other stinking beasts? The château grounds are crawling with them. The Viscount, he's a real coward. He's shaking in his boots. He couldn't kill a thing. Now there's one who's handed in his gun to the Commandant, and with a nice little salute to boot: 'You're very welcome, Messieurs, I'm truly honoured…' It's lucky me and my friends go up to his grounds at night. Otherwise the whole area would be overrun."

"Don't they hear the gunshots?"

"Of course not! It's enormous, almost a forest."

"Do you go there often?" said Madeleine, curious. "I didn't know."

"There's lots of things you don't know, my girl. We go looking for his young tomato plants and beetroot, fruit, anything he's not taking to market. The Viscount…" He paused for a moment, plunged in thought, then added, "The Viscount, he's one of the worst…"

For generations the Sabaries had been tenants of the Montmorts. For generations they had hated one another. The Sabaries said the Montmorts were mean to the poor, haughty, shifty; the Montmorts accused their tenants of having a "bad attitude." They whispered these words as they shrugged their shoulders and raised their eyes to heaven; it was an expression that meant far more than even the Montmorts thought. The Sabaries' way of perceiving poverty, wealth, peace, war, freedom, property, was not in itself less logical than the Montmorts', but it was as contrary to theirs as fire is to water. Now there was even more to complain about. The way the Viscount saw it, Benoît had been a soldier in 1940 and, in the end, it was the soldiers' lack of discipline, their lack of patriotism, their "bad attitude" that had been responsible for the defeat. Benoît, on the other hand, saw in Montmort one of those dashing officers in their tan boots who during those June days had headed towards the Spanish border in their expensive cars, with their wives and suitcases. Then had come "Collaboration"…

"He licks the Germans' boots," Benoît said darkly.

"Be careful," said Madeleine. "You say what you think too much. And don't be rude to that German up there…"

"If he starts chasing after you, I'll…"

"You're crazy!"

"I have eyes."

"Are you going to be jealous of him too?" Madeleine exclaimed.

She regretted it as soon as she had said it: she shouldn't have given substance to her jealous husband's imagination. But after all, what was the use of keeping quiet about something they both knew.

"They're both the same to me," Benoît replied.

These well-groomed, clean-cut men with their quick, witty way of talking-the girls are drawn to them, in spite of themselves, because they're flattered to be sought after by gentlemen… that's what he means, thought Madeleine. If only he knew! Knew she'd loved Jean-Marie from the first moment, the very first moment she saw him lying on that stretcher, exhausted, covered in mud, in his bloody uniform! Loved. Yes. Lying in the dark, deep in that secret part of her heart, she repeated to herself over and over again, "I loved him. There it is. I still love him. I can't help it."

At dawn, the husky crow of the cock pierced the silence and put an end to their sleepless night. They both got up. She went to make the coffee, he to tend the animals.

Lucile Angellier sat in the shade of the cherry trees with a book and some embroidery. It was the only corner of the garden where trees and plants were left to grow untended, for these cherry trees bore little fruit.

But it was blossom time. Against a sky of pure and relentless blue-that deep but lustrous Sèvres blue seen on certain precious pieces of porcelain-floated branches that appeared to be covered in snow. The breath of wind that moved them was still chilly on this day in May; the flowers gently resisted, curling up with a kind of trembling grace and turning their pale stamens towards the ground. The sun shone through them, revealing a pattern of interlacing, delicate blue veins, visible through the opaque petals; this added something alive to the flower's fragility, to its ethereal quality, something almost human, in the way that human can mean frailty and endurance both at the same time. The wind could ruffle these ravishing creations but it couldn't destroy them, or even crush them; they swayed there, dreamily; they seemed ready to fall but held fast to their slim strong branches-branches that had something silvery about them, like the trunk itself, which grew tall and straight, sleek and slender, tinged with greys and purples. Between the clusters of white flowers were long thin leaves; in the shade they looked a delicate green, covered in silvery down; in the sunlight they seemed pink.

The garden ran alongside a narrow road, a country lane dotted with little cottages. This was where the Germans had set up their ammunitions store. A guard marched up and down, beneath a red sign that said in large letters:

VERBOTEN

and further down, in small writing, in French:

KEEP OUT UNDER PENALTY OF DEATH

The soldiers whistled as they groomed their horses and the horses ate the green shoots of the young trees. In the gardens bordering the road, men calmly went about their work. In shirtsleeves, corduroy trousers and straw hats, they tilled, pruned, watered, sowed, planted. Sometimes a German soldier would push open the gate of one of these little gardens to ask for a match to light his pipe, or for a fresh egg, or a glass of beer. The gardener would give him what he wanted; then, leaning on his spade and lost in thought, watch him walk away before turning back to his work with a shrug of the shoulders that was no doubt a reaction to a world of thoughts, so numerous, so deep, so serious and strange that it was impossible to express them in words.

Lucile began to embroider, but soon set down her work. The cherry blossom above her head was attracting wasps and bees; they were coming and going, darting about, diving into the centre of the flowers and drinking greedily, heads down and bodies trembling with a sort of spasmodic delight, while a great golden bumblebee, seemingly mocking these agile workers, swayed in the soft breeze as if on a hammock, barely moving and filling the air with its peaceful golden hum.

From her seat, Lucile could see their German officer at the window; for a few days now he'd had the regiment's Alsatian with him. He was in Gaston Angellier's room, sitting at the Louis XIV desk; he emptied the ashes from his pipe into the blue cup that the elder Madame Angellier used for her son's herbal tea; he tapped his heel absent-mindedly against the gilt bronze mounts that supported the table. The dog had put his snout on the German's leg; he barked and pulled on his chain.

"No, Bubi," the officer told him, in French, and loud enough for Lucile to hear (in this quiet garden, all sound hung in the air for a long time, as if carried by the gentle breeze), "you can't go running about. You will eat all these ladies' lettuces and they will not be happy with you; they will think we are all bad-mannered, crude soldiers. You must stay where you are, Bubi, and look at the beautiful garden."

Читать дальше

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)