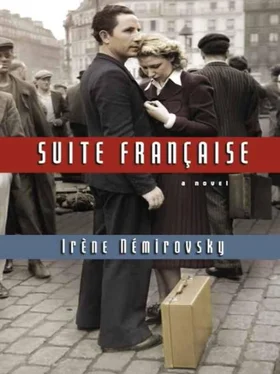

That the manuscript of Suite Française should have survived in such circumstances is extraordinary. It was Denise who put it into a suitcase as she and her sister fled Issy l'Evêque. She had often watched her mother writing-in tiny handwriting to save ink and paper-in the large leatherbound notebook. She took it as a memento of her mother. The suitcase accompanied Denise and Elisabeth from one precarious hiding place to another. After the war, they couldn't bring themselves to read the notebook-having it was enough. Once, Denise tried to look inside to see what was there, but it was too painful. Many years passed, and she and her sister, Elisabeth, who had become an editor in a publishing house under the name Elisabeth Gille, agreed they should entrust their mother's notebook to the Institut Mémoires de l'Édition Contemporaine, an organisation dedicated to documenting memories of the war, in order to preserve it. Before giving it up, Denise decided to type it out. With the help of a large magnifying glass, she began the long, difficult task of deciphering the minuscule handwriting. Soon she discovered that these were not simply notes or a private diary, as she had thought, but a violent masterpiece, a fresco of extraordinary lucidity, a vivid snapshot of France and the French-spineless, defeated and occupied: here was the exodus from Paris; villages invaded by exhausted, hungry women and children battling to find a place to sleep, if only a chair in a country inn; cars piled high with furniture, mattresses and pots and pans, running out of petrol and left abandoned in the roads; the rich trying to save their precious jewels; a German soldier falling in love with a French woman under the watchful eye of her mother-in-law; the simple dignity of a modest couple searching amidst the chaos of the convoys fleeing Paris for a trace of their wounded son…

Denise Epstein sent the manuscript to the publisher Denoël. Sixty-four years after Nemirovsky's death, we are finally able to read the last work of a writer who had held a mirror up to France at its darkest hour.

When Denise Epstein entrusted the manuscript of Suite Française to the archives, she felt tremendous sadness that her sister Elisabeth Gille, who died in 1996, had not been able to read it. Elisabeth had, herself, written Le Mirador ( The Watchtower): a magnificent imagined biography of the mother she never had the chance to know. She was only five years old when Irène Némirovsky died in Auschwitz.

– MYRIAM ANISSIMOV

My thanks go to Olivier Rubinstein and everyone at Éditions Denoël who welcomed this manuscript with enthusiasm and emotion; to Francis Esménard, President and General Director of Albin Michel, who showed great generosity in allowing the publication of a piece of the past of which he was the guardian; to Myriam Anissimov, the link between Romain Gary, Olivier Rubinstein and Irène Némirovsky; and to Jean-Luc Pidoux-Payot, who helped read the manuscript and gave me his valuable advice.

– DENISE EPSTEIN

Irène Némirovsky was born in Kiev in 1903, the daughter of a successful Jewish banker. In 1918, her family fled the Russian Revolution for France, where she became a bestselling novelist. Prevented from publishing when the Germans occupied France in 1940, she moved with her husband and two small daughters from Paris to the safety of the small village of Issy-l 'Evêque (in German-occupied territory). It was here that Irène began writing Suite Française. She died in Auschwitz in 1942.

***

[1]This is an edited version of the preface that appeared in the French edition of Suite Française published by Editions Denoël in 2004.

[2]The infirmary at Auschwitz where prisoners who were too ill to work were confined in atrocious conditions. The SS would periodically pile them into trucks and take them to the gas chambers.

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)