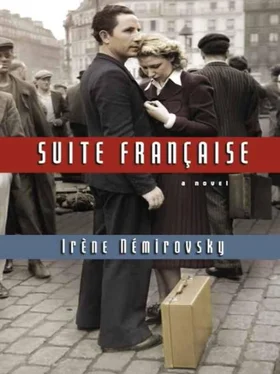

During one of his business trips to Dijon, where he had been a student, Gaston Angellier ran into a former mistress-a hatmaker with whom he'd broken off; he fell in love with her again and more passionately than before; she had his child; he rented a small house for her in the suburbs and arranged his life so he could spend half his time in Dijon. Lucile knew everything but said nothing, out of shyness, scorn or indifference. Then the war…

And now, for a year already, Gaston had been a prisoner. Poor boy… He's suffering, Lucile thought, as the rosary beads slipped mechanically through her fingers. What was he missing most? His comfortable bed, his fine dinners, his mistress? She would like to give him back everything he'd lost, everything that had been taken from him. Yes, everything, even that woman… Realising this, realising the spontaneity and sincerity of this feeling, she also realised how very empty was her heart; it had always been empty-empty of love, empty of jealous hatred. Sometimes her husband treated her harshly. She forgave him his infidelities, but he had never forgotten his father-in-law's bad investments. She could hear the words ringing in her ears, which more than once had made her feel he'd slapped her face: "Imagine if I'd known there wasn't any money!"

She lowered her head. But no-there was no resentment left in her. What her husband had undoubtedly been through since the defeat-the recent battles, flight, capture by the Germans, forced marches, cold, hunger, death all around him, and now being thrown into a prisoner-of-war camp-all that wiped out everything else. "Please just let him come home to everything he loved: his bedroom, his fur-lined slippers, strolling in the garden at dawn, fresh peaches picked from the trellis, his favourite dishes, great roaring fires, all his pleasures, even the ones I don't know about but can imagine, please give them back to him. I don't ask anything for myself. I just want to see him happy. As for me…"

Lost in thought, she let the rosary slip from her fingers and fall to the ground; she realised everyone was standing up, Vespers was over.

Outside, the Germans were standing around in the square. The sunlight glinting off the silver stripes on their uniforms, their light-coloured eyes, their blond hair and their metal belt buckles gave a feeling of cheerfulness, energy and new life to the dusty spot in front of the church which was enclosed within high walls (the remains of ancient ramparts). The Germans were exercising their horses. They had set up a dining area outside: planks of wood the local carpenter had meant to use to make coffins formed a table and benches. The men ate and looked at the townspeople with amused curiosity. You could tell that eleven months of occupation hadn't yet made them blasé. They regarded the French with the same cheerful surprise as in the early days: they found them odd, strange; they couldn't get used to how fast they spoke; they tried to work out whether this defeated people hated them, tolerated them or liked them… They smiled from afar at the young girls and the young girls walked by, proud and scornful-just like on the first day! So the Germans looked down at the crowd of kids around their knees: all the village children were there, fascinated by the uniforms, the horses, the high boots. However loudly their mothers called them, they wouldn't listen. They furtively touched the heavy material of the soldiers' jackets with their dirty fingers. The Germans beckoned to them and filled their hands with sweets and coins.

It felt like a normal, peaceful Sunday. The Germans added a strange note to the scene, but the essential remained unchanged, thought Lucile. There had been some upsetting moments; some of the women (the mothers of prisoners like Madame Angellier or widows from the other war) had hurried home, closed their windows and drawn their curtains so they wouldn't have to see the Germans. In small, dark bedrooms, they cried as they reread old letters; they kissed yellowing photographs draped with black crêpe and decorated with red, white and blue ribbons… But just like every Sunday, the young women gathered in the village square to chat. They weren't going to miss out on an afternoon when they didn't have to work, a holiday, just because of the Germans; they had on their new hats: it was Easter Sunday. Furtively and with inscrutable faces, the men studied the Germans; it was impossible to tell what they were thinking. One German went up to a group of them and asked for a light; they gave him one; they responded to his salute warily; he went away; the men continued talking about the price of cattle. As on every Sunday, the notary went over to the Hôtel des Voyageurs to play cards. Some families were returning from their weekly visit to the cemetery-an almost pleasurable outing in a village where there was nothing much to do: they went in a group; they picked bunches of flowers between the graves. The teaching nuns brought the children out of the church; they made their way through the soldiers; they were impassive beneath their wimples.

"Will they be here long?" murmured the tax inspector to the court clerk, pointing to the Germans.

"Three months, I've heard," he whispered back.

The tax inspector sighed. "That'll force prices up." And, with a mechanical gesture, he rubbed the hand that had been lacerated by a shell explosion in 1915.

Then they changed the subject. The bells that had been ringing since the end of Vespers grew fainter; the final low chimes faded in the evening air.

To get home, the Angellier ladies took a winding lane; Lucile knew its every stone. They walked in silence, responding to greetings with a nod of the head. Madame Angellier was not liked by the villagers, but they felt sorry for Lucile-because she was young, because her husband was a prisoner of war and because she wasn't stuck-up. They sometimes went to ask her opinion about educating their children, about a new blouse, or about how to send a package to Germany. They knew there was an enemy officer lodging at their home-they had the most beautiful house in the village-and they expressed sympathy that they too had to be subjected to the law like everyone else.

"Well, you've certainly got a good one," whispered the dressmaker as she passed them.

"Let's hope they'll be on their way soon," said the chemist.

And a little old lady who was trotting along behind a goat with a soft white coat stood on tiptoe to whisper to Lucile, "I've heard they're all bad and evil, and that they're causing misery to all us poor people."

The goat gave a jump and butted a German officer's long grey cape. He stopped, laughed and wanted to stroke it. But the goat ran off; the frightened little old lady disappeared, and the Angellier ladies closed the door of their house behind them.

The house was the most beautiful for miles. A hundred years old, it was long, low and made of porous yellow stone that in sunlight took on the colour of golden bread. The windows that gave on to the street (those of the most elegant rooms) were carefully sealed, their shutters closed and protected against burglars by iron bars; the small window of the pantry (where they hid prohibited food in an array of different jars) lay behind thick railings whose high spikes in the shape of a fleur-de-lis impaled any cat who wandered by. The front door, painted blue, had the kind of lock you find on prisons and an enormous key that creaked dolefully in the silence. Downstairs, the rooms had a musty smell-that cold smell of an empty house-despite the constant presence of the owners. To prevent the draperies from fading and to protect the furniture, no air or light was allowed in. Through the panes of glass in the hall-the colour of broken bottles-the day seemed murky and overcast; the sideboard, the antlers on the walls, the small antique engravings discoloured by damp were drowned in the gloom.

Читать дальше

![Константин Бальмонт - Константин Бальмонт и поэзия французского языка/Konstantin Balmont et la poésie de langue française [билингва ru-fr]](/books/60875/konstantin-balmont-konstantin-balmont-i-poeziya-francuzskogo-yazyka-konstantin-balmont-et-thumb.webp)