A Thread of Grace

A Novel

Mary Doria Russell

Alla mia famiglia

with thanks to Susa and Tomek,

who made me reach for more

Quello che siete, fummo.

What you are, we were.

Quello che siamo, sarete.

What we are, you shall be.

— FROM AN ITALIAN CEMETERY

ITALIAN JEWS

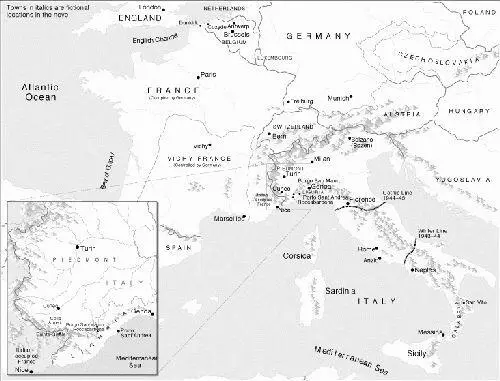

Renzo Leoni, a.k.a. Ugo Messner, Stefano Savoca, Don Gino Righetti

Lidia Segre Leoni, his widowed mother; la nonna (the grandmother)

Tranquillo Loeb, her eldest daughter’s husband

Iacopo Soncini, chief rabbi of Sant’Andrea

Mirella Casutto Soncini, his wife

Angelo, their young son

Altira, their first daughter, deceased

Rosina, their second daughter

Giacomo Tura, elderly Hebrew scribe

JEWISH REFUGEES

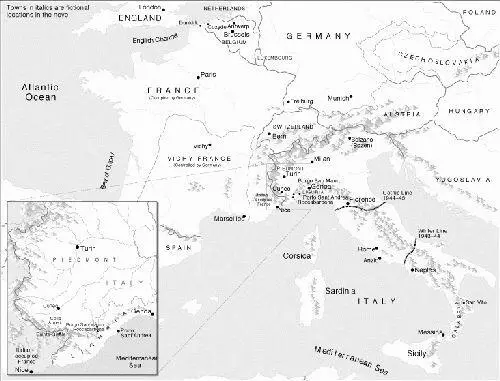

Claudette Blum, Belgian teenager;

Claudia Fiori, la vedova (the widow)

Albert Blum, her father

Duno Brössler, Austrian teenager, partisan

Herrmann and Frieda Brössler, his parents

Liesl and Steffi, his younger sisters

Rivka Ivanova Brössler, his paternal grandmother

Jakub Landau, organizer for the Italian CNL (Committee for National Liberation); il polacco (the Pole)

ITALIAN CATHOLICS

Suora (Sister) Marta, middle-aged nun

Suora Corniglia, novice, later nun; Suora Fossette (Sister Dimples)

Massimo Malcovato, her father; il maggiore (the major)

Don (male honorific) Osvaldo Tomitz, priest, Sant’Andrea

Don Leto Girotti, priest, San Mauro; il prete rosso (the red priest)

Santino Cicala, infantryman, Calabrian draftee

Catarina Dolcino, the Leonis’ landlady; Rina

Serafino Brizzolari, municipal bureaucrat, Sant’Andrea

Antonia Usodimare, proprietress, Pensione Usodimare

Tercilla Lovera, contadina (peasant woman), Santa Chiara

Pierino, Tercilla’s son; il postino (the postman)

Bettina, his sister

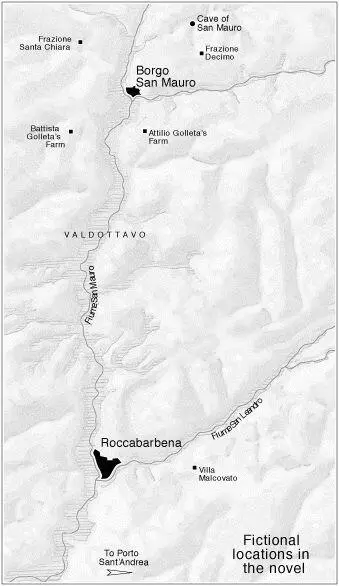

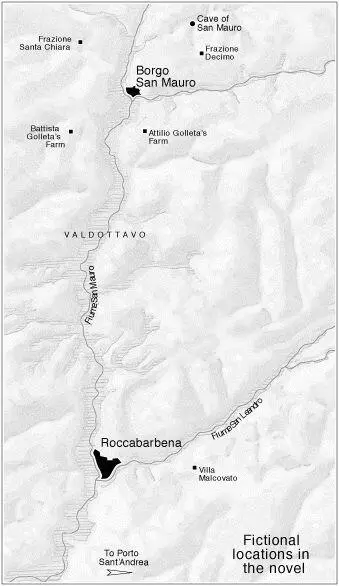

Battista Goletta, Fascist farmer, Valdottavo

Attilio Goletta, his cousin, Communist sharecropper

Tullio Goletta, Attilio’s son, partisan

Adele Toselli, elderly housekeeper, San Mauro rectory

Nello Toselli, her nephew, partisan

Maria Avoni, partisan; la puttana tedesca (the German whore)

Otello Rollero, partisan, interpreter for Simon Henley

BRITISH

Simon Henley, signalman, Special Operations executive

GERMANS

Werner Schramm, deserter, Oberstabsarzt (medical officer) Waffen-SS

Irmgard, his sister, deceased

Erhardt von Thadden, Gruppenführer (division commander) Waffen-SS; the Schoolmaster

Martina, his wife

Helmut Reinecke, his adjutant, Hauptsturmführer (captain), later Standartenführer (colonel, regimental commander)

Ernst Kunkel, Oberscharführer (staff sergeant), aide to von Thadden

Artur Huppenkothen, Oberstpolizei (police colonel), Gestapo

Erna, his sister

AUSTRIA

1907

This is what everyone would remember about his mother: her home was immaculate. Even in a place where cleanliness was pursued with religious zeal, her household was renowned for its faultless order. In Klara’s mind, there was no gradation between purity and filth.

She had sinned as a girl, made pregnant by her married uncle. Adultery stained her soul black, and God punished her as she deserved. Her sin child died.

So did her aunt, and Klara became her uncle’s newest wife, dutifully raising her stepchildren, keeping them very clean and very quiet, so her uncle-husband would not become angry and bring out his leather whip. Her husband was no more merciful than her God.

Her second son died, and then her small daughter. Soon after she buried little Ida, Klara became pregnant again. Her fourth child was a sickly boy whose weakness her uncle-husband despised. Klara was ashamed that her children had died. She hovered over the new baby anxiously, told him constantly that she loved and needed him, hoping that her neighbors would notice how well he was cared for. Hoping that her uncle-husband would come to approve of her son. Hoping that God would hear her pleas, and let this child live.

Her prayers, it seemed, were answered, but the neighbors were bemused by Klara’s mothering. She nursed her little boy for two years. He’d squirm away, or turn his face from her, but she pushed her nipple into his mouth regardless of what troubled him. She fed and fed and fed that child. Food was medicine. Food could ward off numberless, nameless, lurking diseases. “Eat,” she’d plead. “Eat, or you’ll get sick and die.” It was immoderate, even in a village where mothers expected children to swallow whatever was put before them, and to clean their plates.

In adulthood, Klara’s son would have nightmares about suffocation. He would suck on a finger in times of stress, or stuff himself with chocolates. He was obsessed with his body’s odors and became a vegetarian, convinced that this diet reduced his propensity to sweat excessively and improved the aroma of his intestinal gas. He discussed nutritional theories at length but had a poor appetite. He could not watch others eat without trying to spoil their enjoyment. He’d call broth “corpse tea,” and once pointed out that a roast suckling pig looked “just like a cooked baby.”

Whenever he looked in a mirror, he would see his mother’s eyes: china blue and frightened. Frightened of dirt, of her husband, of illness, and of God. Klara’s son was frightened, too. Frightened of priests and hunters, of cigarette smokers and skiers, of liberals, journalists, germs and dirt, of gypsies, judges, and Americans. He was frightened of being wrong, of being weak, of being effeminate. Frightened of poets and of Poles, of academics and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Frightened of moonlight and horses, of snow and water and the dark. Frightened of microbes and spirochetes, of feces, and of old men, and of the French.

The very blood in his veins was dangerous. There were birth defects and feeblemindedness in his incestuous family. His uncle-father was a bastard, and Klara’s son worried all his life that unsavory gossip about his ancestry would become public. He was frightened of sexual intercourse and never had children, afraid his tainted blood would be revealed in them. He was terrified of cancer, which took his mother’s life, and horrified that he had suckled at diseased breasts.

How could anyone live with so much fear?

His solution was to simplify. He sought and seized one all-encompassing explanation for the existence of sin and disease, for all his failures and disappointments. There was no weakness in his parents, his blood, his mind. He was faultless; others were filth. He could not change his china blue eyes, but he could change the world they saw. He would identify the secret source of every evil and root it out, annihilating at a stroke all that threatened him. He would free Europe of pollution and defilement— only health and confidence and purity and order would remain!

Are such grim and comic facts significant, or merely interesting? Here’s another: the doctor who could not cure Klara Hitler’s cancer was Jewish.

Читать дальше