Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, sociology_book, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Children of the Poor

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Children of the Poor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Children of the Poor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Children of the Poor — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Children of the Poor», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

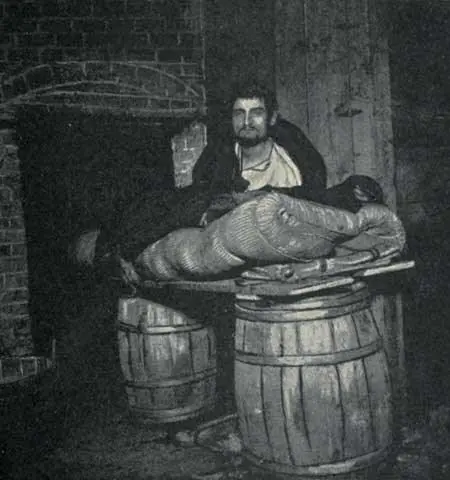

“SLEPT IN THAT CELLAR FOUR YEARS.”

It was only last winter I had occasion to visit repeatedly a double tenement at the lower end of Ludlow Street, which the police census showed to contain 297 tenants, 45 of whom were under five years of age, not counting 3 pedlars who slept in the mouldy cellar, where the water was ankle deep on the mud floor. The feeblest ray of daylight never found its way down there, the hatches having been carefully covered with rags and matting; but freshets often did. Sometimes the water rose to the height of a foot, and never quite soaked away in the dryest season. It was an awful place, and by the light of my candle the three, with their unkempt beards and hair and sallow faces, looked more like hideous ghosts than living men. Yet they had slept there among and upon decaying fruit and wreckage of all sorts from the tenement for over three years, according to their own and the housekeeper’s statements. There had been four. One was then in the hospital, but not because of any ill effect the cellar had had upon him. He had been run over in the street and was making the most of his vacation, charging it up to the owner of the wagon, whom he was getting ready to sue for breaking his leg. Up-stairs, especially in the rear tenement, I found the scene from the cellar repeated with variations. In one room a family of seven, including the oldest daughter, a young woman of eighteen, and her brother, a year older than she, slept in a common bed made on the floor of the kitchen, and manifested scarcely any concern at our appearance. A complaint to the Board of Health resulted in an overhauling that showed the tenement to be unusually bad even for that bad spot; but when we came to look up its record, from the standpoint of the vital statistics, we discovered that not only had there not been a single death in the house during the whole year, but on the third floor lived a woman over a hundred years old, who had been there a long time. I was never more surprised in my life, and while we laughed at it, I confess it came nearer to upsetting my faith in the value of statistics than anything I had seen till then. And yet I had met with similar experiences, if not quite so striking, often enough to convince me that poverty and want beget their own power to resist the evil influences of their worst surroundings. I was at a loss how to put this plainly to the good people who often asked wonderingly why the children of the poor one saw in the street seemed generally such a thriving lot, until a slip of Mrs. Partington’s discriminating tongue did it for me: “Manured to the soil.” That is it. In so far as it does not merely seem so—one does not see the sick and suffering—that puts it right.

Whatever the effect upon the physical health of the children, it cannot be otherwise, of course, than that such conditions should corrupt their morals. I have the authority of a distinguished rabbi, whose field and daily walk are among the poorest of his people, to support me in the statement that the moral tone of the young girls is distinctly lower than it was. The entire absence of privacy in their homes and the foul contact of the sweaters’ shops, where men and women work side by side from morning till night, scarcely half clad in the hot summer weather, does for the girls what the street completes in the boy. But for the patriarchal family life of the Jew that is his strongest virtue, their ruin would long since have been complete. It is that which pilots him safely through shoals upon which the Gentile would have been inevitably wrecked. It is that which keeps the almshouse from casting its shadow over Ludlow Street to add to its gloom. It is the one quality which redeems, and on the Sabbath eve when he gathers his household about his board, scant though the fare be, dignifies the darkest slum of Jewtown.

How strong is this attachment to home and kindred that makes the Jew cling to the humblest hearth and gather his children and his children’s children about it, though grinding poverty leave them only a bare crust to share, I saw in the case of little Jette Brodsky, who strayed away from her own door, looking for her papa. They were strangers and ignorant and poor, so that weeks went by before they could make their loss known and get a hearing, and meanwhile Jette, who had been picked up and taken to Police Headquarters, had been hidden away in an asylum, given another name when nobody came to claim her, and had been quite forgotten. But in the two years that passed before she was found at last, her empty chair stood ever by her father’s, at the family board, and no Sabbath eve but heard his prayer for the restoration of their lost one. It happened once that I came in on a Friday evening at the breaking of bread, just as the four candles upon the table had been lit with the Sabbath blessing upon the home and all it sheltered. Their light fell on little else than empty plates and anxious faces; but in the patriarchal host who arose and bade the guest welcome with a dignity a king might have envied I recognized with difficulty the humble pedlar I had known only from the street and from the police office, where he hardly ventured beyond the door.

But the tenement that has power to turn purest gold to dross digs a pit for the Jew even through this virtue that has been his shield against its power for evil. In its atmosphere it turns too often to a curse by helping to crowd his lodgings, already overflowing, beyond the point of official forbearance. Then follow orders to “reduce” the number of tenants that mean increased rent, which the family cannot pay, or the breaking up of the home. An appeal to avert such a calamity came to the Board of Health recently from one of the refugee tenements. The tenant was a man with a houseful of children, too full for the official scale as applied to the flat, and his plea was backed by the influence of his only friend in need—the family undertaker. There was something so cruelly suggestive in the idea that the laugh it raised died without an echo.

The census of the sweaters’ district gave a total of 23,405 children under six years, and 21,285 between six and fourteen, in a population of something over a hundred and eleven thousand Russian, Polish, and Roumanian Jews in the three wards mentioned; 15,567 are set down as “children over fourteen.” According to the record, scarce one-third of the heads of families had become naturalized citizens, though the average of their stay in the United States was between nine and ten years. The very language of our country was to them a strange tongue, understood and spoken by only 15,837 of the fifty thousand and odd adults enumerated. Seven thousand of the rest spoke only German, five thousand Russian, and over twenty-one thousand, could only make themselves understood to each other, never to the world around them, in the strange jargon that passes for Hebrew on the East Side, but is really a mixture of a dozen known dialects and tongues and of some that were never known or heard anywhere else. In the census it is down as just what it is—jargon, and nothing else.

Here, then, are conditions as unfavorable to the satisfactory, even safe, development of child life in the chief American city as could well be imagined; more unfavorable even than with the Bohemians, who have at least their faith in common with us, if safety lies in the merging through the rising generation of the discordant elements into a common harmony. A community set apart, set sharply against the rest in every clashing interest, social and industrial; foreign in language, in faith, and in tradition; repaying dislike with distrust; expanding under the new relief from oppression in the unpopular qualities of greed and contentiousness fostered by ages of tyranny unresistingly borne. Clearly, if ever there was need of moulding any material for the citizenship that awaits it, it is with this; and if ever trouble might be expected to beset the effort, it might be looked for here. But it is not so. The record shows that of the sixty thousand children, including the fifteen thousand young men and women over fourteen who earn a large share of the money that pays for rent and food, and the twenty-three thousand toddlers under six years, fully one-third go to school. Deducting the two extremes, little more than a thousand children of between six and fourteen years, that is, of school age, were put down as receiving no instruction at the time the census was taken; but it is not at all likely that this condition was permanent in the case of the greater number of these. The poorest Hebrew knows—the poorer he is, the better he knows it—that knowledge is power, and power as the means of getting on in the world that has spurned him so long is what his soul yearns for. He lets no opportunity slip to obtain it. Day and night schools are crowded by his children, who are everywhere forging ahead of their Christian school-fellows, taking more than their share of prizes and promotions. Every synagogue, every second rear tenement or dark back yard, has its school and its school-master with his scourge to intercept those who might otherwise escape. In the census there are put down 251 Jewish teachers as living in these tenements, a large number of whom conduct such schools, so that, as the children form always more than one-half of the population in the Jewish quarter, the evidence is after all that even here, with the tremendous inpour of a destitute, ignorant people, and with the undoubted employment of child labor on a large scale, the cause of progress along the safe line is holding its own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Children of the Poor» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.