Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, sociology_book, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Children of the Poor

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Children of the Poor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Children of the Poor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Children of the Poor — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Children of the Poor», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

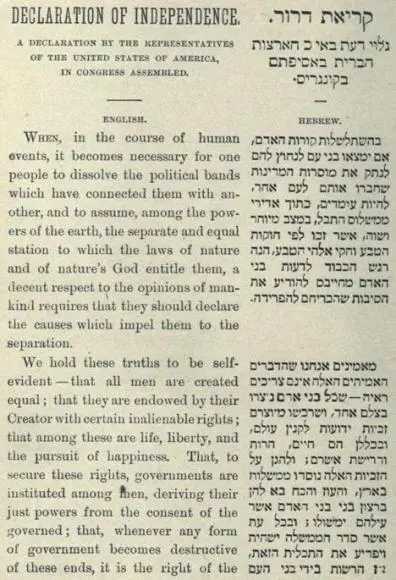

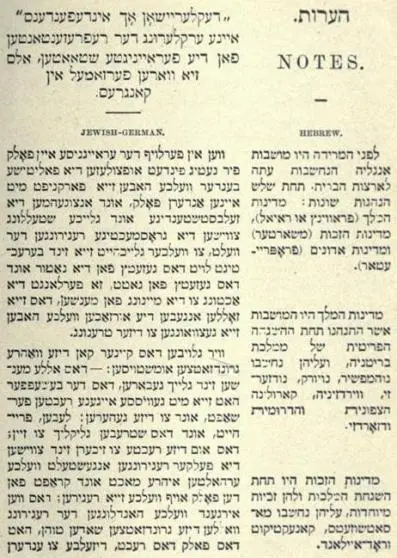

The Declaration of Independence half the children knew by heart before they had gone over it twice. To help them along it is printed in the school-books with a Hebrew translation and another in Jargon, a “Jewish-German,” in parallel columns and the explanatory notes in Hebrew. The Constitution of the United States is treated in the same manner, but it is too hard, or too wearisome, for the children. They “hate” it, says the teacher, while the Declaration of Independence takes their fancy at sight. They understand it in their own practical way, and the spirit of the immortal document suffers no loss from the annotations of Ludlow Street, if its dignity is sometimes slightly rumpled.

“When,” said the teacher to one of the pupils, a little working-girl from an Essex Street sweater’s shop, “the Americans could no longer put up with the abuse of the English who governed the colonies, what occurred then?”

“A strike!” responded the girl, promptly. She had found it here on coming and evidently thought it a national institution upon which the whole scheme of our government was founded.

It was curious to find the low voices of the children, particularly the girls, an impediment to instruction in this school. They could sometimes hardly be heard for the noise in the street, when the heat made it necessary to have the windows open. But shrillness is not characteristic even of the Pig-market when it is noisiest and most crowded. Some of the children had sweet singing voices. One especially, a boy with straight red hair and a freckled face, chanted in a plaintive minor key the One Hundred and Thirtieth Psalm, “Out of the depths” etc., and the harsh gutturals of the Hebrew became sweet harmony until the sad strain brought tears to our eyes.

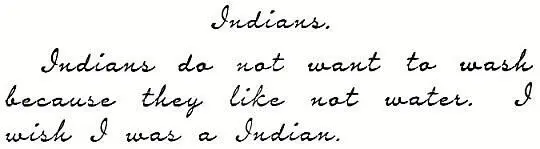

The dirt of Ludlow Street is all-pervading and the children do not escape it. Rather, it seems to have a special affinity for them, or they for the dirt. The duty of imparting the fundamental lesson of cleanliness devolves upon a special school officer, a matron, who makes the round of the classes every morning with her alphabet: a cake of soap, a sponge, and a pitcher of water, and picks out those who need to be washed. One little fellow expressed his disapproval of this programme in the first English composition he wrote, as follows:

Despite this hint, the lesson is enforced upon the children, but there is no evidence that it bears fruit in their homes to any noticeable extent, as is the case with the Italians I spoke of. The homes are too hopeless, the grind too unceasing. The managers know it and have little hope of the older immigrants. It is toward getting hold of their children that they bend every effort, and with a success that shows how easily these children can be moulded for good or for bad. Nor do they let go their grasp of them until the job is finished. The United Hebrew Charities maintain trade-schools for those who show aptness for such work, and a very creditable showing they make. The public school receives all those who graduate from what might be called the American primary in East Broadway.

The smoky torches on many hucksters’ carts threw their uncertain yellow light over Hester Street as I watched the children troop homeward from school one night. Eight little pedlers hawking their wares had stopped under the lamp on the corner to bargain with each other for want of cash customers. They were engaged in a desperate but vain attempt to cheat one of their number who was deaf and dumb. I bought a quire of note-paper of the mute for a cent and instantly the whole crew beset me in a fierce rivalry, to which I put a hasty end by buying out the little mute’s poor stock—ten cents covered it all—and after he had counted out the quires, gave it back to him. At this act of unheard-of generosity the seven, who had remained to witness the transfer, stood speechless. As I went my way, with a sudden common impulse they kissed their hands at me, all rivalry forgotten in their admiration, and kept kissing, bowing, and salaaming until I was out of sight. “Not bad children,” I mused as I went along, “good stuff in them, whatever their faults.” I thought of the poor boy’s stock, of the cheapness of it, and then it occurred to me that he had charged me just twice as much for the paper I gave him back as for the penny quire I bought. But when I went back to give him a piece of my mind the boys were gone.

CHAPTER IV.

TONY AND HIS TRIBE

I HAVE a little friend somewhere in Mott Street whose picture comes up before me. I wish I could show it to the reader, but to photograph Tony is one of the unattained ambitions of my life. He is one of the whimsical birds one sees when he hasn’t got a gun, and then never long enough in one place to give one a chance to get it. A ragged coat three sizes at least too large for the boy, though it has evidently been cropped to meet his case, hitched by its one button across a bare brown breast; one sleeve patched on the under side with a piece of sole-leather that sticks out straight, refusing to be reconciled; trousers that boasted a seat once, but probably not while Tony has worn them; two left boots tied on with packing twine, bare legs in them the color of the leather, heel and toe showing through; a shock of sunburnt hair struggling through the rent in the old straw hat; two frank, laughing eyes under its broken brim—that is Tony.

He stood over the gutter the day I met him, reaching for a handful of mud with which to “paste” another hoodlum who was shouting defiance from across the street. He did not see me, and when my hand touched his shoulder his whole little body shrank with a convulsive shudder, as from an expected blow. Quick as a flash he dodged, and turning, out of reach, confronted the unknown enemy, gripping tight his handful of mud. I had a bunch of white pinks which a young lady had given me half an hour before for one of my little friends. “They are yours,” I said, and held them out to him, “take them.”

Doubt, delight, and utter bewilderment struggled in the boy’s face. He said not one word, but when he had brought his mind to believe that it really was so, clutched the flowers with one eager, grimy fist, held them close against his bare breast, and, shielding them with the other, ran as fast as his legs could carry him down the street. Not far; fifty feet away he stopped short, looked back, hesitated a moment, then turned on his track as fast as he had come. He brought up directly in front of me, a picture a painter would have loved, ragamuffin that he was, with the flowers held so tightly against his brown skin, scraped out with one foot and made one of the funniest little bows.

“Thank you,” he said. Then he was off. Down the street I saw squads of children like himself running out to meet him. He darted past and through them all, never stopping, but pointing back my way, and in a minute there bore down upon me a crowd of little ones, running breathless with desperate entreaty: “Oh, mister! give me a flower.” Hot tears of grief and envy—human passions are much the same in rags and in silks—fell when they saw I had no more. But by that time Tony was safe.

And where did he run so fast? For whom did he shield the “posy” so eagerly, so faithfully, that ragged little wretch that was all mud and patches? I found out afterward when I met him giving his sister a ride in a dismantled tomato-crate, likely enough “hooked” at the grocer’s. It was for his mother. In the dark hovel he called home, to the level of which all it sheltered had long since sunk through the brutal indifference of a drunken father, my lady’s pinks blossomed, and, long after they were withered and yellow, still stood in their cracked jar, visible token of something that had entered Tony’s life and tenement with sweetening touch that day for the first time. Alas! for the last, too, perhaps. I saw Tony off and on for a while and then he was as suddenly lost as he was found, with all that belonged to him. Moved away—put out, probably—and, except the assurance that they were still somewhere in Mott Street, even the saloon could give me no clue to them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Children of the Poor» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.