Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, sociology_book, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Children of the Poor

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Children of the Poor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Children of the Poor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Children of the Poor — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Children of the Poor», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

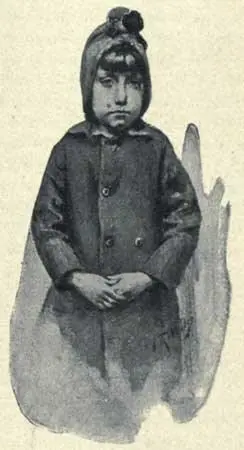

I gained Tony’s confidence, almost, in the time I knew him. There was a little misunderstanding between us that had still left a trace of embarrassment when Tony disappeared. It was when I asked him one day, while we were not yet “solid,” if he ever went to school. He said “sometimes,” and backed off. I am afraid Tony lied that time. The evidence was against him. It was different with little Katie, my nine-year-old housekeeper of the sober look. Her I met in the Fifty-second Street Industrial School, where she picked up such crumbs of learning as were for her in the intervals of her housework. The serious responsibilities of life had come early to Katie. On the top floor of a tenement in West Forty-ninth Street she was keeping house for her older sister and two brothers, all of whom worked in the hammock factory, earning from $4.50 to $1.50 a week. They had moved together when their mother died and the father brought home another wife. Their combined income was something like $9.50 a week, and the simple furniture was bought on instalments. But it was all clean, if poor. Katie did the cleaning and the cooking of the plain kind. They did not run much to fancy cooking, I guess. She scrubbed and swept and went to school, all as a matter of course, and ran the house generally, with an occasional lift from the neighbors in the tenement, who were, if anything, poorer than they. The picture shows what a sober, patient, sturdy little thing she was, with that dull life wearing on her day by day. At the school they loved her for her quiet, gentle ways. She got right up when asked and stood for her picture without a question and without a smile.

“I SCRUBS.”—KATIE, WHO KEEPS HOUSE IN WEST FORTY-NINTH STREET.

“What kind of work do you do?” I asked, thinking to interest her while I made ready.

“I scrubs,” she replied, promptly, and her look guaranteed that what she scrubbed came out clean.

Katie was one of the little mothers whose work never ends. Very early the cross of her sex had been laid upon the little shoulders that bore it so stoutly. Tony’s, as likely as not, would never begin. There were ear-marks upon the boy that warranted the suspicion. They were the ear-marks of the street to which his care and education had been left. The only work of which it heartily approves is that done by other people. I came upon Tony once under circumstances that foreshadowed his career with tolerable distinctness. He was at the head of a gang of little shavers like himself, none over eight or nine, who were swaggering around in a ring, in the middle of the street, rigged out in war-paint and hen-feathers, shouting as they went: “Whoop! We are the Houston Streeters.” They meant no harm and they were not doing any just then. It was all in the future, but it was there, and no mistake. The game which they were then rehearsing was one in which the policeman who stood idly swinging his club on the corner would one day take a hand, and not always the winning one.

The fortunes of Tony and Katie, simple and soon told as they are, encompass as between the covers of a book the whole story of the children of the poor, the story of the bad their lives struggle vainly to conquer, and the story of the good that crops out in spite of it. Sickness, that always finds the poor unprepared and soon leaves them the choice of beggary or starvation, hard times, the death of the bread-winner, or the part played by the growler in the poverty of the home, may vary the theme for the elders; for the children it is the same sad story, with little variation, and that rarely of a kind to improve. Happily for their peace of mind, they are the least concerned about it. In New York, at least, the poor children are not the stunted repining lot we have heard of as being hatched in cities abroad. Stunted in body perhaps. It was said of Napoleon that he shortened the average stature of the Frenchman one inch by getting all the tall men killed in his wars. The tenement has done that for New York. Only the other day one of the best known clergymen in the city, who tries to attract the boys to his church on the East Side by a very practical interest in them, and succeeds admirably in doing it, told me that the drill-master of his cadet corps was in despair because he could barely find two or three among half a hundred lads verging on manhood, over five feet six inches high. It is queer what different ways there are of looking at a thing. My medical friend finds in the fact that poverty stunts the body what he is pleased to call a beautiful provision of nature to prevent unnecessary suffering: there is less for the poverty to pinch then. It is self-defence, he says, and he claims that the consensus of learned professional opinion is with him. Yet, when this shortened sufferer steals a loaf of bread to make the pinching bear less hard on what is left, he is called a thief, thrown into jail, and frowned upon by the community that just now saw in his case a beautiful illustration of the operation of natural laws for the defence of the man.

Stunted morally, yes! It could not well be otherwise. But stunted in spirits—never! As for repining, there is no such word in his vocabulary. He accepts life as it comes to him and gets out of it what he can. If that is not much, he is not justly to blame for not giving back more to the community of which by and by he will be a responsible member. The kind of the soil determines the quality of the crop. The tenement is his soil and it pervades and shapes his young life. It is the tenement that gives up the child to the street in tender years to find there the home it denied him. Its exorbitant rents rob him of the schooling that is his one chance to elude its grasp, by compelling his enrolment in the army of wage-earners before he has learned to read. Its alliance with the saloon guides his baby feet along the well-beaten track of the growler that completes his ruin. Its power to pervert and corrupt has always to be considered, its point of view always to be taken to get the perspective in dealing with the poor, or the cart will seem to be forever getting before the horse in a way not to be understood. We had a girl once at our house in the country who left us suddenly after a brief stay and went back to her old tenement life, because “all the green hurt her eyes so.” She meant just what she said, though she did not know herself what ailed her. It was the slum that had its fatal grip upon her. She longed for its noise, its bustle, and its crowds, and laid it all to the green grass and the trees that were new to her as steady company.

From this tenement the street offered, until the kindergarten came not long ago, the one escape, does yet for the great mass of children—a Hobson’s choice, for it is hard to say which is the most corrupting. The opportunities rampant in the one are a sad commentary on the sure defilement of the other. What could be expected of a standard of decency like this one, of a household of tenants who assured me that Mrs. M–, at that moment under arrest for half clubbing her husband to death, was “a very good, a very decent, woman indeed, and if she did get full, he (the husband) was not much.” Or of the rule of good conduct laid down by a young girl, found beaten and senseless in the street up in the Annexed District last autumn: “Them was two of the fellers from Frog Hollow,” she said, resentfully, when I asked who struck her; “them toughs don’t know how to behave theirselves when they see a lady in liquor.”

Hers was the standard of the street, the other’s that of the tenement. Together they stamp the child’s life with the vicious touch which is sometimes only the caricature of the virtues of a better soil. Under the rough burr lie undeveloped qualities of good and of usefulness, rather, perhaps, of the capacity for them, that crop out in constant exhibitions of loyalty, of gratitude, and true-heartedness, a never-ending source of encouragement and delight to those who have made their cause their own and have in their true sympathy the key to the best that is in the children. The testimony of a teacher for twenty-five years in one of the ragged schools, who has seen the shanty neighborhood that surrounded her at the start give place to mile-long rows of big tenements, leaves no room for doubt as to the influence the change has had upon the children. With the disappearance of the shanties—homesteads in effect, however humble—and the coming of the tenement crowds, there has been a distinct descent in the scale of refinement among the children, if one may use the term. The crowds and the loss of home privacy, with the increased importance of the street as a factor, account for it. The general tone has been lowered, while at the same time, by reason of the greater rescue-efforts put forward, the original amount of ignorance has been reduced. The big loafer of the old day, who could neither read nor write, has been eliminated to a large extent, and his loss is our gain. The tough who has taken his place is able at least to spell his way through “The Bandits’ Cave,” the pattern exploits of Jesse James and his band, and the newspaper accounts of the latest raid in which he had a hand. Perhaps that explains why he is more dangerous than the old loafer. The transition period is always critical, and a little learning is proverbially a dangerous thing. It may be that in the day to come, when we shall have got the grip of our compulsory school law in good earnest, there will be an educational standard even for the tough, by which time he will, I think, have ceased to exist from sheer disgust, if for no other reason. At present he is in no immediate danger of extinction from such a source. It is not how much book-learning the boy can get, but how little he can get along with, and that is very little indeed. He knows how to make a little go a long way, however, and to serve on occasion a very practical purpose; as, for instance, when I read recently on the wall of the church next to my office in Mulberry Street this observation, chalked in an awkward hand half the length of the wall: “Mary McGee is engagd to the feller in the alley.” Quite apt, I should think, to make Mary show her colors and to provoke the fight with the rival “feller” for which the writer was evidently spoiling. I shall get back, farther on, to the question of the children’s schooling. It is so beset by lies ordinarily as to be seldom answered as promptly and as honestly as in the case of a little fellow whom I found in front of St. George’s Church, engaged in the æsthetic occupation of pelting the Friends’ Seminary across the way with mud. There were two of them, and when I asked them the question that estranged Tony, the wicked one dug his fists deep down in the pockets of his blue-jeans trousers and shook his head gloomily. He couldn’t read; didn’t know how; never did.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Children of the Poor» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.