Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jacob August Riis - The Children of the Poor» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, sociology_book, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Children of the Poor

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Children of the Poor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Children of the Poor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Children of the Poor — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Children of the Poor», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This dump of which I have spoken as furnishing the background of the social life of Mulberry Street, has lately challenged attention as a slum annex to the Bend, with fresh horrors in store for defenceless childhood. To satisfy myself upon this point I made a personal inspection of the dumps along both rivers last winter and found the Italian crews at work there making their home in every instance among the refuse they picked from the scows. The dumps are wooden bridges raised above the level of the piers upon which they are built to allow the discharge of the carts directly into the scows moored under them. Under each bridge a cabin had been built of old boards, oil-cloth, and the like, that had found its way down on the carts; an old milk-can had been made into a fireplace without the ceremony of providing stove-pipe or draught, and here, flanked by mountains of refuse, slept the crews of from half a dozen to three times that number of men, secure from the police, who had grown tired of driving them from dump to dump and had finally let them alone. There were women at some of them, and at four dumps, three on the North River and one on the East Side, I found boys who ought to have been at school, picking bones and sorting rags. They said that they slept there, and as the men did, why should they not? It was their home. They were children of the dump, literally. All of them except one were Italians. That one was a little homeless Jew who had drifted down at first to pick cinders. Now that his mother was dead and his father in a hospital, he had become a sort of fixture there, it seemed, having made the acquaintance of the other lads.

A CHILD OF THE DUMP.

Two boys whom I found at the West Nineteenth Street dumps sorting bones were as bright lads as I had seen anywhere. One was nine years old and the other twelve. Filthy and ragged, they fitted well into their environment—even the pig I had encountered at one of the East River dumps was much the more respectable, as to appearance, of the lot—but were entirely undaunted by it. They scarcely remembered anything but the dump. Neither could read, of course. Further down the river I came upon one seemingly not over fifteen, who assured me that he was twenty-one. I thought it possible when I took a closer look at him. The dump had stunted him. He did not even know what a letter was. He had been there five years, and garbage limited his mental as well as his physical horizon.

Enough has been said to show that the lot of the poor child of the Mulberry Street Bend, or of Little Italy, is not a happy one, courageously and uncomplainingly, even joyously, though it be borne. The stories of two little lads from the region of Crosby Street always stand to me as typical of their kind. One I knew all about from personal observation and acquaintance; the other I give as I have it from his teachers in the Mott Street Industrial School, where he was a pupil in spells. It was the death of little Giuseppe that brought me to his home, a dismal den in a rear tenement down a dark and forbidding alley. I have seldom seen a worse place. There was no trace there of a striving for better things—the tenement had stamped that out—nothing but darkness and filth and misery. From this hole Giuseppe had come to the school a mass of rags, but with that jovial gleam in his brown eyes that made him an instant favorite with the teachers as well as with the boys. One of them especially, little Mike, became attached to him, and a year after his cruel death shed tears yet, when reminded of it. Giuseppe had not been long at the school when he was sent to an Elizabeth Street tenement for a little absentee. He brought her, shivering in even worse rags than his own; it was a cold winter day.

“This girl is very poor,” he said, presenting her to the teacher, with a pitying look. It was only then that he learned that she had no mother. His own had often stood between the harsh father and him when he came home with unsold evening papers. Giuseppe fished his only penny out of his pocket—his capital for the afternoon’s trade. “I would like to give her that,” he said. After that he brought her pennies regularly from his day’s sale, and took many a thrashing for it. He undertook the general supervision of the child’s education, and saw to it that she came to school every day. Giuseppe was twelve years old.

There came an evening when business had been very bad, so bad that he thought a bed in the street healthier for him than the Crosby Street alley. With three other lads in similar straits he crawled into the iron chute that ventilated the basement of the Post-office on the Mail Street side and snuggled down on the grating. They were all asleep, when fire broke out in the cellar. The three climbed out, but Giuseppe, whose feet were wrapped in a mail-bag, was too late. He was burned to death.

The little girl still goes to the Mott Street school. She is too young to understand, and marvels why Giuseppe comes no more with his pennies. Mike cries for his friend. When, some months ago, I found myself in the Crosby Street alley, and went up to talk to Giuseppe’s parents, they would answer no questions before I had replied to one of theirs. It was thus interpreted to me by a girl from the basement, who had come in out of curiosity:

“Are youse goin’ to give us any money?” Poor Giuseppe!

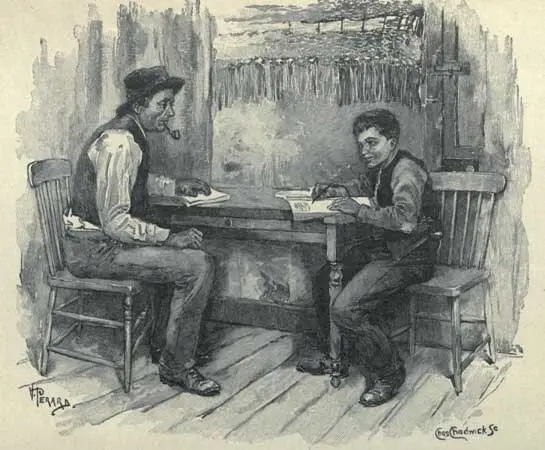

PIETRO LEARNING TO MAKE AN ENGLIS’ LETTER.

My other little friend was Pietro, of whom I spoke before. Perhaps of all the little life-stories of poor Italian children I have come across in the course of years—and they are many and sad, most of them—none comes nearer to the hard every-day fact of those dreary tenements than his, exceptional as was his own heavy misfortune and its effect upon the boy. I met him first in the Mulberry Street police-station, where he was interpreting the defence in a shooting case, having come in with the crowd from Jersey Street, where the thing had happened at his own door. With his rags, his dirty bare feet, and his shock of tousled hair, he seemed to fit in so entirely there of all places, and took so naturally to the ways of the police-station, that he might have escaped my notice altogether but for his maimed hand and his oddly grave yet eager face, which no smile ever crossed despite his thirteen years. Of both, his story, when I afterward came to know it, gave me full explanation. He was the oldest son of a laborer, not “borned here” as the rest of his sisters and brothers. There were four of them, six in the family besides himself, as he put it: “2 sisters, 2 broders, 1 fader, 1 modder,” subsisting on an unsteady maximum income of $9 a week, the rent taking always the earnings of one week in four. The home thus dearly paid for was a wretched room with a dark alcove for a bed-chamber, in one of the vile old barracks that until very recently preserved to Jersey Street the memory of its former bad eminence as among the worst of the city’s slums. Pietro had gone to the Sisters’ school, blacking boots in a haphazard sort of way in his off-hours, until the year before, upon his mastering the alphabet, his education was considered to have sufficiently advanced to warrant his graduating into the ranks of the family wage-earners, that were sadly in need of recruiting. A steady job of “shinin’” was found for him in an Eighth Ward saloon, and that afternoon, just before Christmas, he came home from school and putting his books away on the shelf for the next in order to use, ran across Broadway full of joyous anticipation of his new dignity in an independent job. He did not see the street-car until it was fairly upon him, and then it was too late. They thought he was killed, but he was only crippled for life. When, after many months, he came out of the hospital, where the company had paid his board and posed as doing a generous thing, his bright smile was gone; his “shining” was at an end, and with it his career as it had been marked out for him. He must needs take up something new, and he was bending all his energies, when I met him, toward learning to make the “Englis’ letter” with a degree of proficiency that would justify the hope of his doing something somewhere at sometime to make up for what he had lost. It was a far-off possibility yet. With the same end in view, probably, he was taking nightly writing-lessons in his mother-tongue from one of the perambulating schoolmasters who circulate in the Italian colony, peddling education cheap in lots to suit. In his sober, submissive way he was content with the prospect. It had its compensations. The boys who used to worry him, now let him alone. “When they see this,” he said, holding up his scarred and misshapen arm, “they don’t strike me no more.” Then there was his fourteen months old baby brother who was beginning to walk, and could almost “make a letter.” Pietro was much concerned about his education, anxious evidently that he should one day take his place. “I take him to school sometime,” he said, piloting him across the floor and talking softly to the child in his own melodious Italian. I watched his grave, unchanging face.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Children of the Poor» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Children of the Poor» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.