Once we heard the door to the old man’s bedroom close, Lexie said, “The way he lives in this stuffy cave. It’s not really living, is it? That’s why I come to stay with him. My parents would much rather I stay somewhere else when they go out of the country, but I want to come here. I’m still working on changing him.”

While the Schwa pondered his object, I pondered what she had said. I didn’t think Crawley could be changed. My dad once told me that people don’t change when they get older, they just get more so. I imagine that when Crawley was younger, he was the kind of kid who always saw the glass half empty instead of half full, and had a better relationship with his dog than with the neighborhood kids. In seventy-five years of living, half empty became bone-dry, solitary became isolated, and one dog became fourteen.

“Saltshaker!” said the Schwa.

“Wrong. It’s the queen from a chessboard,” said Lexie.

“Your grandfather is who he is,” I told her. “You should just live your own life, and let him live his. Or not live his, I guess.”

“I disagree,” said the Schwa. “I think people can be changed— but usually it takes a traumatic experience.”

“You mean like brain damage?” I asked, then immediately thought about the Schwa’s father and was sorry I said it.

“Trauma comes in many forms,” Lexie said. “It changes you, but it doesn’t always change you for the better.” She handed me my next object; something like a pen.

“Well, if it’s directed trauma,” said the Schwa, “maybe it could change you for the better.”

“Like radiation,” I said. They both waited for me to explain myself. This was easier said than done, on accounta the intuitive part of my brain was three steps ahead of the thinking part. It was like lightning before thunder. But sometimes you see lightning and the thunder never comes. Just like the way I’ll sometimes blurt out something that sounds smart, but if you ask me to explain it, the universe could end before you get an answer.

“We’re listening,” Lexie said.

I fiddled with my object, stalling for time. “You know, radiation . . .” And for once it all came to me—what I meant, and what I was holding. “Just like this . . . laser pointer!” I must have known in some subconscious way all along.

“I get it,” said the Schwa. “Radiation can be like a nuclear missile, or it can be directed, like a medical treatment that saves your life.”

“Yeah,” I said. “When my uncle got cancer, they used radiation therapy on him.”

“And he lived?” asked Lexie.

“Well, no—but that’s just because he got hit by a garbage truck.”

“So,” said Lexie, “what my grandfather needs is trauma therapy. Something as dangerous as radiation, but focused, and in the proper dose.”

“You’ll figure it out,” I told her.

“Yes,” she said, “I will.”

I gave her the plastic kneecap, but I could tell her mind was no longer on the game. She was already thinking of a way to traumatize her grandfather.

“Maybe if we put our heads together,” the Schwa said, “we’ll come up with something quicker.”

I squirmed. “Three heads are a crowd,” I said. But whatever Lexie’s opinion was, she kept it quiet.

***

That Friday night I had Lexie all to myself, since the Schwa’s aunt came over every Friday night. I took her to a concert in the park at an outdoor amphitheater.

The music was salsa—not my favorite, but that was okay. Concerts have a way of making music you don’t regularly like, likable. I guess it’s because when the people around you really like it, some of that soaks into you. It’s called osmosis, something I learned about in science—probably by osmosis, since it isn’t like I was listening. I was listening to the music, though, and so was Lexie. I watched the way she moved to it, and I didn’t even feel self-conscious watching her because she couldn’t see me doing it.

We had great seats—right smack in the middle. The handicapped section. I have to admit I felt guilty—not only because I wasn’t handicapped, but because Lexie was the most unhandicapped handicapped person I’d ever laid eyes on.

“Are you having fun?” she asked when the band took a break.

I shrugged. “Yeah, sure,” I said, trying not to sound like I was having as much fun as I really was, because what if she took my real enthusiasm for fake enthusiasm?

“I like this band,” Lexie said. “Their sound’s not all muddy. I can hear all seven musicians.”

I thought about that. I had been watching them for more than half an hour, and now that they were off the stage, I couldn’t tell you how many musicians there had been.

“Amazing,” I said. “You’re like one of those mentalists. You can see things with your mind.”

She reached over to pet Moxie, who sat next to her in the aisle, content as long as he was petted every few minutes. “Some people are good at being blind, others aren’t,” and then she smiled. “I’m very good.”

“Great. We’ll call you the Amazing Lexis.”

“I like that.”

“And now,” I announced, “the Amazing Lexis, through her supersonic skills of perceptive-ability”—she giggled—«will tell me how many fingers I am holding up.” I held up three fingers.

“Um ... two!”

“Wow!” I said. “You’re right! That’s amazing!”

“You’re lying.”

“How do you know?”

“There’s only a one-in-four chance that I’d get it right—one-in-five if you counted your thumb as a finger—so the odds were against it. And besides, ‛lie’ was written all over your voice.”

I laughed, truly impressed. “The Amazing Lexis strikes again.”

Lexie grinned for a moment, and I noticed how her smile fit with her half-closed eyes. It was like the face you make when you’re tasting something unbelievable, like my dad’s eggplant Parmesan, which is poison in anyone else’s hands.

Lexie reached over to pet Moxie again. “Too bad Calvin couldn’t come with us.”

“Oh,” I said. “Yeah, right.” I probably would have gone the whole night without thinking about him once, and now I felt a little guilty about that—and annoyed that I felt guilty—and irritated that I was annoyed. “Why would you want the Schwa on a date with us, anyway?”

“This isn’t a date,” Lexie said. “People don’t get paid to go on a date.”

She thought she had me there. “Well, you’re not supposed to know I’m getting paid—and since you know and are still letting me take you out, it is a date.”

She didn’t say anything to that. Maybe she just couldn’t argue with my logic.

“There’s something ... unusual about Calvin,” she said.

“He’s visibly impaired,” I told her. “Observationally challenged.”

“He thinks he’s invisible?”

“He is invisible ... kind of.”

Lexie screwed up her lips so they looked kind of like the red scrunchy she wore in her hair, then said, “No, it’s more than that. There’s something else about him that either you don’t know or you’re just not telling me.”

“Well, his mother either disappeared in Waldbaum’s supermarket or got chopped up by his father, who sent pieces to all fifty states. No one’s really sure which it is.”

“Hmm,” Lexie said. “That’s bound to have an effect on a person, either way.”

“He seems okay to me.”

“He’s very sweet,” Lexie added.

“Ripe is the word,” I said. “He’s gotta start wearing deodorant.”

The lights in the amphitheater started to dim, and the crowd began cheering for the band to start.

Читать дальше

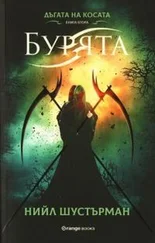

![Нил Шустерман - Жнец [litres]](/books/418707/nil-shusterman-zhnec-litres-thumb.webp)