“Are my zits giving you messages in Braille?”

She giggled at that, and I prayed to God that the whitehead I’d been nursing with Clearasil didn’t decide it was time to blow.

Now she moved her fingers up to my eye sockets, brushing both of my brows with her thumb before checking out the bridge of my nose. “You have good bone structure,” she said, which is fine for dinosaurs in the Museum of Natural History, but not exactly the compliment you want to hear.

“That’s the best you can say, huh?”

“Good bone structure is important,” she said. “No matter how handsome or pretty you think you are, without bone structure to back it up, it doesn’t mean a thing.”

I let her continue, closing my eyes as she gently pressed her thumbs against my sockets, perhaps testing to see whether or not there was a brain behind my eyeballs.

“You have very nice eyes,” she said.

Her fingers slipped down the side of my nose and began to travel the rim of my nostrils, which, I have to tell you, felt just a little too familiar. Then, before I could say anything about it, her fingers were brushing gently across my lips. It tickled. I was glad she couldn’t see how much I was blushing, but I wondered if she could feel the heat rising to my face.

“Seen enough?”

“Almost.” And then—God’s honest truth—she pushed her fingers just the slightest bit between my lips, and started to move them back and forth across my teeth.

“I fink oo sood shtop now,” I said.

“Hmm,” she said, ignoring me. “You’ve got braces.”

This was not going well. I wanted to be anywhere but there at that moment. Then she said, “I like braces. It gives a person texture.”

Having a girl’s fingers explore the texture of my dental work was uncharted territory for me. What did this mean? Did it mean we were going out? Was this like the blind version of “first base”? Or was this some other sport altogether—a sport I didn’t know how to play? What if this was like cricket, which I watched once and it made no sense to me. So here’s this girl with her fingertips on my teeth, which I guess is first base in a cricket match, and I’m wondering what happens if she wants to find other textures in there.

Then she took her hands away. I took a deep breath of relief. “So,” I said, “do you like what you see?”

She smiled. “Yeah. Yeah, I do.”

I wondered if I would get a turn now, but I was afraid to ask.

“Hi, Antsy!”

The Schwa caught me totally by surprise and I jumped. I had no idea how long he had been standing there watching. “Jeez— do you have to do that?”

“I was wondering when you’d say something,” Lexie said.

I turned to Lexie. “You knew he was there?”

“Of course. I could hear him breathing. What did he call you?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Just a nickname.”

“She saw me!” said the Schwa. “She actually saw me!”

“She didn’t see you, she’s blind.”

“But she knew I was here!” The Schwa was getting all excited now. “Hey, Antsy, maybe we can do another set of experiments with Lexis. See if she’s immune to the Schwa Effect. Maybe it’s genetic—her grandfather usually notices me, too.”

Lexie smiled. “Antsy? He called you Antsy?”

I threw up my hands. This was the classic three’s-a-crowd scenario, and right now three felt more like Times Square on New Year’s Eve. “Schwa, could you just go and walk some dogs?”

“I got all day.”

“Aren’t you going to introduce us?” asked Lexie.

I sighed. “Lexie, meet the Schwa. Schwa, meet Lexie.”

“Calvin,” he said. “Pleased to meet you.”

By now Prudence and Envy were both getting restless. We walked them back home, and I took them upstairs alone. When I came back outside, Lexie was touching the Schwa’s face.

“Hey!” I shouted, running back to them.

“I wanted Lexie to see me,” the Schwa said, “like she saw you.”

“What if she doesn’t want to see you?”

Lexie’s eyebrows furrowed as she keyboarded across the Schwa’s face. “Hmm ... that’s interesting.”

“What?” the Schwa asked. “What is it?”

“I don’t know. It’s like . . . It’s like I can’t get a clear impression. Your face feels...”

“Invisible,” I suggested.

“No,” said Lexie, searching for the right word. Now she moved her fingers across his face more intently than she had searched mine. And although she touched his lips, she didn’t check out his teeth. If she did, I would have thrown a hemorrhage, although I can’t really say why.

“His face is ... pure,” she said. “Flavorless—like sweet-cream ice cream.”

The Schwa smiled. “Yeah? My face is like ice cream?”

“Sweet cream,” I reminded him. “It has no taste.”

“Yes, it does,” said Lexie. “It’s just very subtle.”

“Nobody likes it,” I said.

“It’s my favorite,” Lexie answered.

The Schwa only grinned, and threw a disgustingly happy glance in my direction.

Now let’s be clear on something here. I had only just met Lexie, and she wasn’t really my type. I mean, I’m Italian, she’s blind. It was a mixed relationship. But seeing her fingers on Schwa’s face ... I don’t know, it did something to me.

The two of us had lunch down in Crawley’s restaurant. Lobster on the house. Schwa, in his slippery way, appeared at the table and tried to squeeze in, but I was ready for him. I quickly brought down two dogs for him to walk, and no sooner had I put the leashes in his hands than the maitre d’ threw a conniption fit about health codes, and quickly shooed Schwa and the dogs out the back way.

“Your friend’s funny,” Lexie said after he was gone.

“Yeah,” I said, “Funny in the head.” Right away I felt this unpleasant stab of guilt for turning on the Schwa like that.

Lexie smirked, and for a moment, I forgot she was blind, because I knew she was seeing everything.

9. Maybe They Had It Right in France Because Getting My Head Lopped Off by a Guillotine Would Have Been Easier

Life went from being a bad haircut to being an algebra exam. In algebra, things only make sense once you’re done, there are no shortcuts, and you always have to show your work. The problem becomes more complicated the second you add a new variable. I mean, solving for x was hard enough, but with me, Lexie, and the Schwa, too, I had to solve for x, y, and z. When things get that complicated, you might as well just put down your pencil and admit defeat.

The thing is, the Schwa was not just your typical variable—he was like i, the imaginary number. The square root of negative one, which doesn’t exist, yet does in its own weird way. The Schwa was on the cusp of being there and not being there, which I guess is why he clung so tightly to Lexie and me.

The Schwa called me the next morning to invite me over for lunch. I was busy working on my social studies report, the history of capital punishment—which wasn’t a bad topic, since it involved beheadings and electrocutions—but it was Sunday. iSunday and homework go together like oil and water, which, by the way, is what they boiled criminals in during the early Middle Ages. Oil, not water, although I didn’t realize the hot water I would find myself in by accepting the Schwa’s lunch invitation.

Mr. Schwa wasn’t wearing his painter’s clothes when he answered the door, but the jeans and shirt he wore did have little paint splotches all over them. He also held a butcher knife.

“Can I help you?”

If those paint splatters on his clothes had been red, I probably would have run off screaming.

Читать дальше

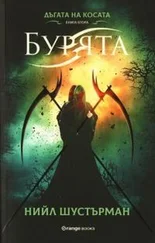

![Нил Шустерман - Жнец [litres]](/books/418707/nil-shusterman-zhnec-litres-thumb.webp)