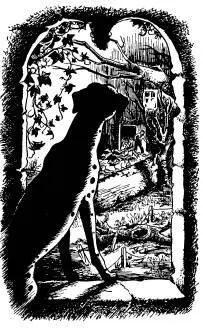

The narrow, twisting stairs went up through five floors of the Folly, most of them full of broken furniture, old trunks, and all manner of rubbish. On the top floor was a deep bed of straw, brought up by the Colonel in a sack. But what interested Missis far more was the narrow window—surely it must look towards Hell Hall?

She ran to see. Yes, beyond the tree-tops and a neglected orchard was the back of the black house—which was as ugly as the front, though it did not have such a frightening expression. At one side was a large stableyard.

“Is that where the puppies will come out?” she asked.

“Yes, yes,” said the Colonel, “but it won’t be for—well, for some time yet.”

“I shall never sleep until I’ve seen them,” said Missis.

“Yes, you will, because I shall talk you to sleep,” said the Colonel. “Your husband has asked me to tell him the history of Hell Hall. Now come and lie down.”

Pongo was as anxious to see the puppies as Missis was, but he knew they should sleep first, so he coaxed her to lie down. The Colonel pulled the straw round both of them.

“It’s chilly in here—not that I feel it,” he said. Then he sent the cat to start collecting food for the next meal, and began to talk in his rumbling voice. This was the story he told.

Hell Hall had once been an ordinary farmhouse named Hill Hall—it had been built by a farmer named Hill. It was about two hundred years old, the same age as the farm where the Sheepdog and the cat lived.

“The two houses are quite a bit alike,” said the Colonel, “only our place is painted white and well cared for. I remember Hell Hall before it was painted black and it really wasn’t bad at all.”

The farmer named Hill had got into debt and sold Hill Hall to an ancestor of Cruella de Vil’s, who liked its lonely position on the wild heath. He intended to pull the farmhouse down and build himself a fantastic house which was to be a mixture of a castle and a cathedral, and had begun by building the surrounding wall and the Folly. (The Colonel had heard all this while visiting the Vicarage.)

Once the wall, with its heavy iron gates, was finished, strange rumours began to spread. Villagers crossing the heath at night heard screams and wild laughter. Were there prisoners behind the prison-like wall? People began to count their children carefully.

“Some of the stories—Well, I shan’t tell you just as you’re falling asleep,” said the Colonel. “I didn’t hear them at the Vicarage. But I will tell you something—because it won’t upset you as it naturally upset the villagers. It was said that this de Vil fellow had a long tail. I didn’t hear that at the Vicarage, either.”

Missis had taken in very little of this and was now fast asleep, but Pongo was keenly interested.

“By this time,” the Colonel went on, “people were calling the place Hell Hall, and the de Vil chap plain devil. The end came when the men from several villages arrived one night with lighted torches, prepared to break open the gates and burn the farmhouse down. But as they approached the gates a terrific thunderstorm began and put the torches out. Then the gates burst open—seemingly of their own accord—and out came de Vil, driving a coach and four. And the story is that lightning was coming not from the skies but from de Vil—blue forked lightning. All the men ran away screaming and never came back. And neither did de Vil. The house stood empty for thirty years. Then someone rented it. It’s been rented again and again, but no one ever stays.”

“And it still belongs to the de Vil family?” asked Pongo.

“There’s only Cruella de Vil left of the family now. Yes, she owns it. She came down here some years ago and had the house painted black. It’s red inside, I’m told. But she never lived here. She lets the Baddun brothers have it rent free, as caretakers. I wouldn’t let them take care of any kennel of mine.”

Those were the last words Pongo heard, for, as the story ended, sleep wrapped him round. The Sheepdog stood looking down at the peaceful couple.

“Well, they’re in for a shock,” he thought, and then lumbered his way downstairs.

It was less than an hour later when Missis opened her eyes. She had been dreaming of the puppies, she had heard them barking—and they were barking! She sprang out of the straw and dashed to the window. No pup was to be seen, but she could hear the barking clearly—it was coming from inside the black house. Then the barking grew louder, the door to the stableyard opened, and out came a stream of puppies.

Missis blinked. Surely her puppies could not have grown so much in less than a week? And surely she had not had so many puppies? More and more were hurrying out; the whole yard was filling up with fine, large, healthy Dalmatian puppies, but—Missis raised her head in a wail of despair. These puppies were not hers at all! The whole thing was a mistake! Her puppies were still lost, perhaps starving, perhaps even dead. Again and again she howled in anguish.

Her first howl had wakened Pongo. He was beside her in a couple of seconds and staring at the yard full of milling, tumbling puppies. And they were still coming out of the house, rather smaller puppies now—

And then they saw him—smaller, even, than they had remembered. Lucky! There was no mistaking that horseshoe of spots on his back. And after him came Roly Poly, falling over his feet as usual. Then Patch and the tiny Cadpig and all the others—all well, all lashing their tails, all eager to drink at the low troughs of water that stood about in the yard.

“Look, Patch is helping the Cadpig to find a place,” said Missis delightedly. “But what does it mean? Where have all those other puppies come from?”

Dazed as he was with sleep, Pongo’s keen brain had gone into instant action. He saw it all. Cruella must have begun stealing puppies months before—soon after that evening when she had said she would like a Dalmatian fur coat. The largest pups in the yard looked at least five months old. Then they went down and down in size. Smallest and youngest of all were his own puppies, which must obviously have been the last to be stolen.

He had barely finished explaining this to Missis when the Sheepdog reached the top of the stairs—he had been downstairs getting in fresh water and had heard Missis howl.

“Well, now you know,” he said. “I was hoping you could have had your sleep out first.”

“But why are you both looking so worried?” asked Missis. “Our puppies are safe and well.”

“Yes, my dear. You go on watching them,” said Pongo gently. Then he turned to the Colonel.

“You come downstairs and have a drink, my boy,” said the Colonel.

Oh, how Pongo needed that drink!

“And now stroll down to the pond with me,” said the Colonel, gripping the handle of a little tin bucket in his teeth. “You won’t feel like trying to sleep any more just at present.”

Pongo felt he would never be able to sleep again.

“I blame myself for letting you in for this shock,” said the Colonel as they went out into the early morning sunlight. “Because you can’t blame the Lieutenant. She’s not a trained observer. When she told me the place was ‘seething with Dalmatian puppies’ I naturally thought she meant your puppies only. After all, fifteen puppies can do quite a bit of seething. It was only yesterday, after I’d made the Folly my headquarters and could see over the wall, that I found out the true facts. Of course I sent the news over yesterday’s Twilight Barking but couldn’t reach you.”

Читать дальше