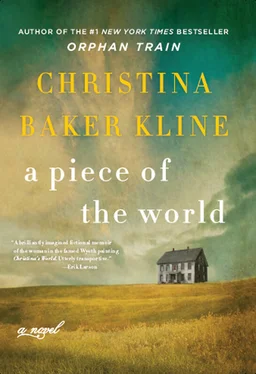

As I did with Orphan Train , I tried to adhere to the actual historical facts wherever possible in writing A Piece of the World . Like the real Christina, my character was born in 1893 and grew up in an austere house on a barren hill in Cushing, Maine, with three brothers. A hundred years earlier, three of her ancestors had fled from Massachusetts in midwinter, changing the spelling of their family name to Hathorn along the way, to escape the taint of association with their relative John Hathorne, the presiding judge in the Salem Witch Trials and the only one who never recanted. On the scaffold, one of the convicted witches put a curse on Hathorne’s family, and the specter of the trials clung to the family through generations; it was said among the townspeople of Cushing that those three Hathorns had brought the witches with them when they fled. Another relative, Nathaniel Hawthorne—who also changed the spelling of his name to obscure the family connection—wrote about his great-great grandfather Hathorne’s unremitting ruthlessness in Young Goodman Brown , a tale about how those who fear the darkness in themselves are the most likely to see it in other people.

Another true story became an equally significant part of my novel. For generations, the house on the hill was known as the Hathorn house. But early in the winter of 1890, in the midst of a raging snowstorm, a fishing vessel bringing lime to make mortar and bricks became stuck in the ice of the nearby St. George River channel, and a young Swedish sailor named Johan Olauson was stranded. The ship captain, a Cushing native, offered to take him in. Olauson walked across the ice to Captain Maloney’s cottage, where he hunkered down for the winter, waiting for the thaw to melt the ice so he could put back to sea. Just up the hill from the cottage was a magnificent white house belonging to a respected sea captain, Samuel Hathorn. Johan soon learned the story of the family on Hathorn Hill: they were on the brink of “daughtering out,” meaning that no male heirs had survived to carry on the family name. Within several months, the young sailor had taught himself English, changed his name to John Olson, and made his presence known to the “spinster” Hathorn daughter, Kate—at 34, six years his senior. In a one-month span, Samuel Hathorn died and John Olson married Kate, taking over the farm. Their first child, Christina, was born a year later, and the big white homestead became known as the Olson house. The Hathorns had daughtered out.

BY ALL ACCOUNTS, from an early age Christina was an active and vibrant presence. She had a lust for life, a fierce intelligence, and a determination not to be pitied, despite the degenerative disease that stole her mobility. (Though she was never correctly diagnosed in her lifetime, neurologists now believe she had a syndrome called Charcot-Marie-Tooth, a hereditary disorder that damages the nerves to the arms and legs.) Christina refused to use a wheelchair; as she became increasingly immobilized she took to dragging herself around. Several years ago the actress Claire Danes portrayed Christina Olson in an hour-long tour-de-force dance performance that emphasized her ferocious desire to move freely despite her devastating disease.

Quick of wit and sharp of tongue, Christina was a force to be reckoned with. Late in life—with her straw-like hair and hooked nose, her spinsterhood and independent nature—she was rumored among some of the townspeople of Cushing to be a witch herself. Andrew Wyeth variously called her a “witch” and a “queen” and “the face of Maine.”

Wyeth first appeared at Christina’s front door—along with Betsy James, his future wife, who’d been visiting the Olson farm since she was a girl—in 1939. He was twenty-two, Betsy seventeen, Christina forty-six. He began coming around almost daily, talking with Christina for hours, and sketching and painting landscapes, still lifes, and the house itself, which fascinated him. “The world of New England is in that house,” Wyeth said “—spidery, like crackling skeletons rotting in the attic—dry bones. It’s like a tombstone to sailors lost at sea, the Olson ancestor who fell from the yardarm of a square-rigger and was never found. It’s the doorway of the sea to me, of mussels and clams and sea monsters and whales. There’s a haunting feeling there of people coming back to a place.”

In time, Wyeth began incorporating Christina into his paintings. “What interested me about her was that she’d come in at odd places, odd times,” he said. “The great English painter John Constable used to say that you never have to add life to a scene, for if you sit quietly and wait, life will come—sort of an accident in the right spot. That happened to me all the time—happened lots with Christina.”

For the next thirty years, Christina was Andrew Wyeth’s muse and his inspiration. In each other, I believe, they came to recognize their own contradictions. Both embraced austerity but craved beauty; both were curious about other people and yet pathologically private. They were perversely independent and yet reliant on others to take care of their basic needs: Wyeth on his wife Betsy and Christina on Alvaro.

“My memory can be more of a reality than the thing itself,” Wyeth said. “I kept thinking about the day I would paint Christina in her pink dress, like a faded lobster shell I might find on a beach, crumpled. I kept building her in my mind—a living being there on a hill whose grass was really growing. Someday she was going to be buried under it. Soon her figure was actually going to crawl across the hill in my picture toward that dry tinderbox of a house on top. I felt the loneliness of that figure—perhaps the same that I felt myself as a kid. It was as much my experience as hers.”

“In Christina’s World,” Wyeth said, “I worked on that hill for a couple of months, that grass, building up the ground to make it come toward you, a surge of earth, like the whole planet . . . When it came time to lay Christina’s figure against the planet I’d created for her all those weeks, I put this pink tone on her shoulder—and it almost blew me across the room.”

In becoming an artist’s muse—a seemingly passive role—Christina finally achieved the autonomy and purpose she craved her entire life. Instinctively, I believe, Wyeth managed to get at the core of Christina’s self. In the painting she is paradoxically singular and representative, vibrant and vulnerable. She is solitary, but surrounded by the ghosts of her past. Like the house, like the landscape, she perseveres. As an embodiment of the strength of the American character, she is vibrant, pulsating, immortal.

For many reasons, this was the most difficult book I’ve ever written. Christina Olson was a real person, as were—and are—many of the people in this novel, and I did a tremendous amount of research into her life, her family, and her relationship with Andrew Wyeth. But at a certain point I had to let the research go and allow my characters to move the story forward. Ultimately, A Piece of the World is a work of fiction. Biographical facts regarding the characters in this book should not be sought in these pages. I hope readers intrigued by the story I tell here will explore the nonfiction accounts I mention in the acknowledgments. And above all else, I hope I have done this story justice.

I WAS BORN in Cambridge, England, and spent my early years with my parents and younger sister in a small nearby village called Swaffham Bulbeck, in a house built in the thirteenth century. When you stood in the living room and looked up, you could see the circular outline of what had once been the hole in the roof above the space where the original inhabitants had built fires. There was no refrigerator or central heating; we used an icebox and a small gas heater that required coins to operate. Several years later we moved to Tennessee and lived on an abandoned farm, in an unheated house that had only recently been wired for electricity. Eventually we moved to Maine, into a normal house with basic amenities. But we spent weekends, holidays, and summers at a camp my father built on a tiny island on a lake with an outdoor pump for water, gas lanterns and candles for light, a fireplace for warmth, and an outhouse. We snowshoed across the frozen lake in the winter and chipped ice from the front door to get inside. My sisters and I would huddle in our coats around the hearth until the fire my parents built was robust enough to warm us.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу