Klaus Schwab - Stakeholder Capitalism

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Klaus Schwab - Stakeholder Capitalism» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: economics, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Stakeholder Capitalism

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:9781119756149

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stakeholder Capitalism: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Stakeholder Capitalism»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Individual agency:

A clearly defined social contract:

Planning for future generations:

Better measures of economic success: Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet

Stakeholder Capitalism

Stakeholder Capitalism — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Stakeholder Capitalism», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

China's rise represents an incredible milestone, but it shouldn't distract us from the even bigger picture. The global trends we outlined in Chapter 2are as valid for Asia as they are for the Western world. The entire world has been on an unsustainable growth path, endangering the environment and the fate of future generations. Moreover, the economic growth that China, India, and others achieved in recent years was often shared just as unequally as in the West.

For China, the inequality challenge is equally present, but the greater problem may be the looming burden of its debt. Until the financial crisis in 2008, China's total debt-to-GDP ratio of 170 percent was in line with that of other emerging markets, as Martin Wolf of the Financial Times noted in a 2018 essay. 123But in the decade since then, it has risen explosively. In July 2019, it stood at 303 percent, according to an IIF estimate, and after the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis it ballooned to 317 percent. 124

This is a dangerous trend because much of Chinese debt is owned by nonfinancial state-owned enterprises and local governments who may use debt to boost economic output in the short run. However, with marginal returns on public and private investments sharply decreasing in recent years, top-line economic growth is decelerating as a result, and the debt overhang is becoming increasingly concerning. Trade tensions, a decline in population growth, or other factors may trigger a further slowdown in growth. If that happens, a Chinese crisis may reverberate globally.

Finally, while China led the world in installing new wind and solar facilities in the past few years, and President Xi at the UN General Assembly in September 2020 announced it wanted to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, 125there are still some major hurdles left to get there. First, in spite of the new Chinese ambitions, the building of new renewable energy facilities in the country slowed in 2019, a trend that continued into the new decade. 126Second, China saw its oil demand rebound quicker than elsewhere after the COVID crisis, with 90 percent of its pre-COVID demand recovered by early summer of 2020. It was a good sign for the global economic recovery but less good news for emissions, as China is the world's second-largest consumer of oil, behind the US. And third, Bloomberg reported, 127Asia's share in total global coal demand will expand from about 77 percent now to around 81 percent by 2030. China, which produces and burns about half of global coal, and Indonesia were the world's largest coal producers, and each also produced significantly more in 2019 than the previous year, BP indicated in its 2020 Statistical Review of World Energy. 128

Emerging Markets in China's Slipstream

China wasn't the only economy to make enormous leaps forward in the past few decades. In its slipstream, countries from Latin America to Africa and from the Middle East to Southeast Asia also rose. China needed commodities, and many of its fellow emerging markets could provide them.

Indeed, while China is a giant in both geographical and demographical terms, it is more modest in its possession of the world's most important resources, with the exception perhaps of rare-earth minerals. As it grew, constructing new cities, operating factories, and expanding its infrastructure, it needed the help of others to supply it with the necessary inputs.

This was a blessing for other emerging markets, especially those in China's immediate vicinity (including Russia, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN region, and Australia) and those who had struggled to attain high growth rates before (including many developing countries in Latin America and Africa).

China's rise, in fact, fueled a great emerging-markets bonanza. A glance at the World Bank's and UN's trade databases for 2018 129gives an insight into just how much China's rise contributed to that of other countries. China today is the world's second-largest importer of goods and services, to the tune of some $2 trillion. In reaching that size, it gave more than one economy a huge boost, buying loads of commodities every year.

In 2018, 130for example, it imported huge amounts of oil from Russia ($37 billion), Saudi Arabia ($30 billion), and Angola ($25 billion). For mining ores, besides Australia ($60 billion), it counted on Brazil ($19 billion) and Peru ($11 billion). Precious stones such as diamonds and gold were imported mostly through Switzerland, with South Africa a runner-up. China also bought copper from Chile ($10 billion) and Zambia ($4 billion), while various types of rubber came mostly from Thailand ($5 billion).

Those were just the raw materials. As China climbed up the value chain, it started to outsource some of its production, moving factories to the new low-cost economies of Vietnam, Indonesia, and Ethiopia, to name but a few. The technology it once needed to import through foreign joint ventures, China now created itself, allowing it to become an importer of the finished goods it had produced abroad and an exporter of them to consumers in other countries.

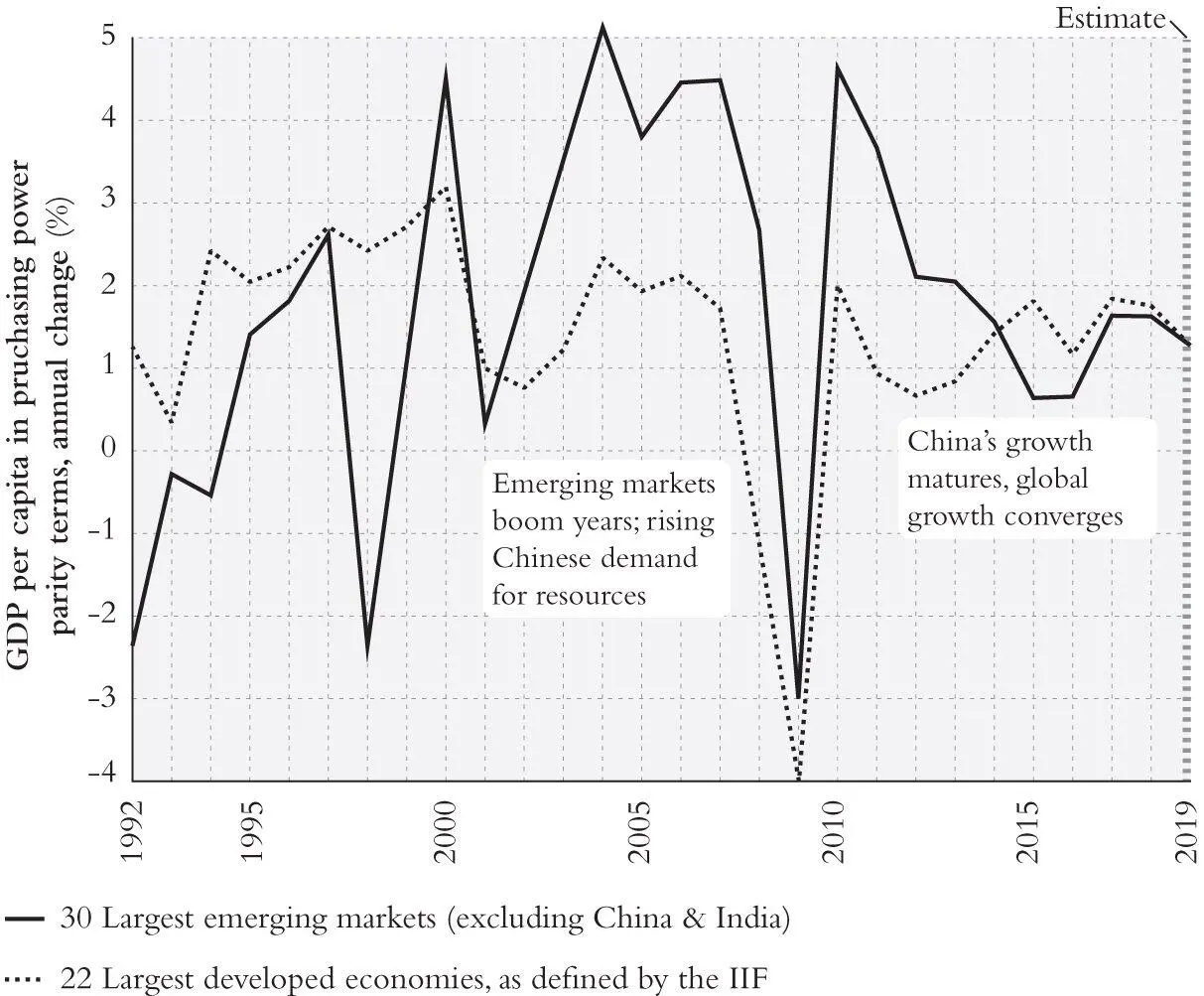

It is no surprise then, that just like China, many emerging markets experienced their own wonder years in the past two decades. The trend started slowly in the 1990s, when the world moved toward free trade, and it accelerated in the years following China's inauguration into the WTO in 2001. For over a decade, from 2002 to 2014, the Financial Times calculated, 131emerging markets consistently outperformed their developed world peers, not just in growth but in per capita GDP growth ( Figure 3.1). The result was, as economist Richard Baldwin dubbed it, “the great convergence”: 132the incomes and GDP of poorer, emerging markets, moved closer to that of richer, developed markets.

Unfortunately, that trend in recent years has come to an end for most emerging markets, bar China and India. Since 2015, per capita GDP growth in the 30 largest emerging markets fell back below that of the 22 largest developed ones. The fact that China's growth in those years fell to under 7 percent is no exception. Its appetite for commodities is no longer insatiable, which put the brakes on their prices and trading volumes.

Figure 3.1 After a China-Fuelled Boom in the 2000s, Emerging Markets Growth Lags That of Developed Economies Again

Source: Redrawn from IMF, Real GDP growth, 2020.

That doesn't mean growth has petered out everywhere. Three regions in particular continue to perform well:

First there is the ASEAN economic community, home to some 650 million people, including from large and growing countries such as Indonesia (264 million people), the Philippines (107 million), Vietnam (95 million), Thailand (68 million), and Malaysia (53 million). 133, 134Though an extremely diverse group of nations, both culturally and economically, the whole ASEAN community is set to return to the GDP growth path it had built up in the last few years before the COVID crisis hit, averaging some 5 percent per year. 135In the IMF's latest World Economic Outlook, dating from October 2020, the five largest ASEAN economies were in fact expected to experience a smaller than global average economic contraction in 2020 (–3.4 percent) and return to a 6.2 percent growth in 2021. 136

One important reason for their sustained growth is that as a group, they are the closest to being the next factory of the world, a title China held before them. Wages in countries like Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia are often lower than in China, and their proximity to China and some of the world's most important sea lanes make for easy export to consumers around the world. Already, hundreds of multinationals from countries including China, the US, Europe, Korea, and Japan are producing there.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Stakeholder Capitalism»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Stakeholder Capitalism» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Stakeholder Capitalism» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.