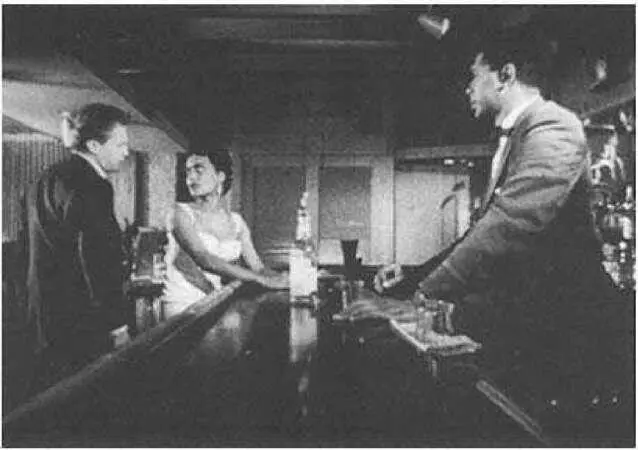

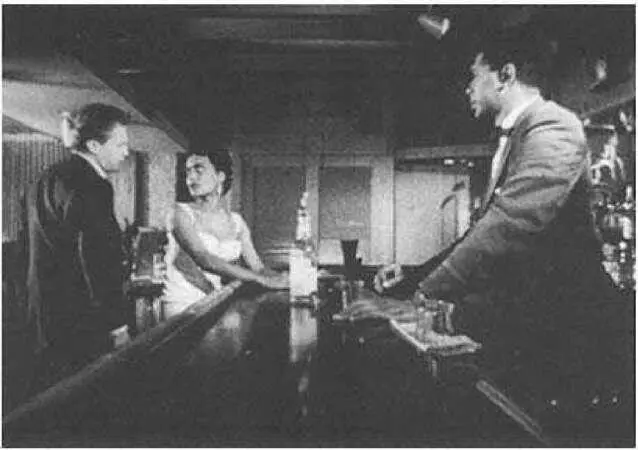

The private eye as "White Negro." Ralph Meeker, Madi Comfort, and Art Loggins in Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

In the years following the civil rights movement, films made by black people became more widely visible. Significantly, the first important commercial breakthrough by a black director in Hollywood was Ossie Davis's Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), an adaptation of the Chester Himes's roman noir about Harlem police detectives Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnston. In place of Himes's sinister, subversive irony, Davis employs an old-fashioned ethnic humor, in much the same way that Hollywood in the 1930s tried to play Hammett and Chandler in broadly comic style. Partly as a result of Cotton Comes to Harlem, however, a truly radical transformation of black images suddenly appeared in 1971, when a pair of low-budget crime pictures directed by black men became surprise hits. Melvin Van Peebles's Sweet Sweetback's Baadassss Song and Gordon Parks's Shaft were grounded respectively in the themes of criminal adventure and private-eye fiction, but they gave new life to old forms by turning the black male into a sexually potent hero. Both had crossover appeal for young white audiences of the Vietnam era, and both were symptomatic of a broad countercultural reaction against liberal stereotypes. Of the two, the independently produced Sweet Sweetback was by all odds the most threatening; it gave full vent to separatist black rage, allowing its criminal protagonist (Van Peebles) to fulfill every nightmare of white society and to emerge unconquered. Shaft, which was produced at MGM, was a straightforward entertainment, accepting the legal establishment in the qualified manner of a typical private-eye movie.

Harry Belafonte in Odds against Tomorrow (1959).

Its eponymous hero (Richard Roundtree) laughed at the law but was unwilling to join a group of black-power revolutionaries; he was also mildly cooperative with the one white policeman in New York who seemed not to be a racist.

One of the striking differences between these last two films and the standard noir thrillers of the 1940s was their refusal to depict the male hero as in any way flawed, compromised, or even vulnerable. Responding to decades of emasculated or nearly invisible black people on the screen, Van Peebles and Parks created black supermen, and they spawned a brief series of low-budget imitations that can be listed among the most phallocentric pictures this side of Mickey Spillane or James Bond. In one of the Shaft sequels, the hero tries to resist being typed as a sybaritic stud: "I'm not James Bond," he insists. "I'm Sam Spade." He nevertheless remains a Bond-like, leather-coated warrior who lives in a sophisticated Village pad and is irresistible to women. The hero of Sweetback is not only sexually prodigious but also downright ruthless, and he was clearly an influence on Gordon Parks's next film, Superfly (1972), a highly successful criminal adventure featuring a slick cocaine dealer who dresses and behaves like a Harlem pimp.

Thomas Bogle observes that Van Peebles and Parks "assiduously sought to avoid the stereotype of the asexual tom," but in doing so, they reproduced an equally old and distorted image of the "wildly sexual" black hedonist (240). They also tended to glamorize the dark side of town. Parks was especially good at photographing downtrodden New York locales, such as the porn movie theaters along 42nd Street and the gloomy alleys of Amsterdam Avenue, in ways that made the urban ghetto look pregnant with adventure. In fact, his neorealist color photography and night-for-night chase sequences had a strong influence on Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, thereby helping to establish a visual style for American neo-noir as a whole. Despite their broad influence and their escapist fantasies, however, Van Peebles and Parks could not be completely absorbed into the mainstream; their early work still seems refreshingly different from Hollywood, if only because of its rough, documentary texture and its unusually angry, rebellious tone.

By the 1990s, the black middle class had grown sufficiently to provide greater opportunities for black stars and directors; nevertheless, various forms of de facto segregation still existed, and the black underclass in the cities had reached crisis proportions. In the face of these circumstances, the urban thriller or policier emerged (for better or worse) as the form of popular movie entertainment that most consistently dealt with black issues. The two white directors who were most influenced by black film noir in the 1970s Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino showed an interest not only in black themes but also in the most powerful word in the English language. In Scorsese's case, the term nigger is often spoken by Italian working-class characters who suffer from a racial inferiority complex and feel a compulsive need to identify themselves as white. In Tarantino's, the effect is somewhat different. The gangsters and tough guys in Pulp Fiction use the term over and over again (along with bitch), while at the same time the film tries to protect itself against charges of racism by means of the plot and the casting: John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson are linked together like Huck and Jim; Bruce Willis saves a black man from being raped by a couple of white southern racists; and Tarantino himself plays a gangster's accomplice who is married to a black woman. Audiences probably respond to the racial epithets in mixed ways, much as they once responded to Archie Bunker on TV. Some liberal viewers may regard the repeated nigger as a daringly realistic gesture, or as an attempt to divest a repressed word of its ugly power; racist viewers, however, are likely to experience a secret thrill.

Richard Roundtree in Shaft (1971).

(Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

If many of the old images of blackness persist in Hollywood noir, there is also a new kind of African-American presence. A wide range of hip-hop or "gangsta" films directed by African Americans depict a black criminal milieu in a fashion similar to traditional rogue-cop or caper movies, and the black actor Larry Fishburne has performed impressively in a series of ambiguous roles derived from classic noirmost notably as the undercover narcotics agent who is drawn to crime in Deep Cover (1992) and as the ex-CIA operative in Bad Company (1994). This chapter cannot do justice to all the recent "noirs by noirs," and for that reason among others, I recommend Manthia Diawara's essay on the topic in Shades of Noir (1993). Diawara uses Chester Himes as a paradigmatic African-American author of noir fiction, and he makes an important distinction between two types of crime movies by African-American directors: on the one hand are more-or-less-traditional romance narratives and gangster films such as A Rage in Harlem (1991) and New Jack City (1991); and on the other hand are realist, socially critical pictures such as Boyz N the Hood (1991), Juice (1992), and Clockers (1995). Both types combine noir motifs with rap music, but the socially critical pictures tend to appropriate the highly commodified youth culture and its associated black nationalism on behalf of ''an ideology of black progress and modernism." 26

Читать дальше