In contrast, Carl Franklin's Devil in a Blue Dress invites direct comparison with Chinatown and the tradition of hard-boiled private-eye literature. Like Walter Mosley's novel, the film begins in 1948 Los Angeles, near the spot on Central Avenue where Raymond Chandler placed the opening scenes of Farewell, My Lovely. As in Chandler, the plot involves a search for a missing woman who has changed her identity, and it leads to a fairly typical disclosure of sexual perversion and political corruption. But because the action is viewed from a different social, economic, and racial perspective, familiar motifs of urban noir are either intensified or neatly reversed.

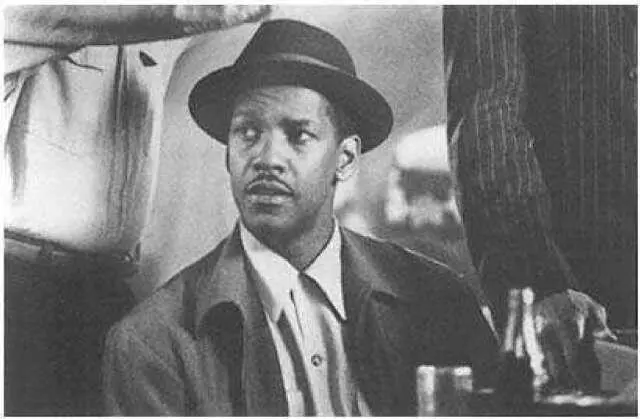

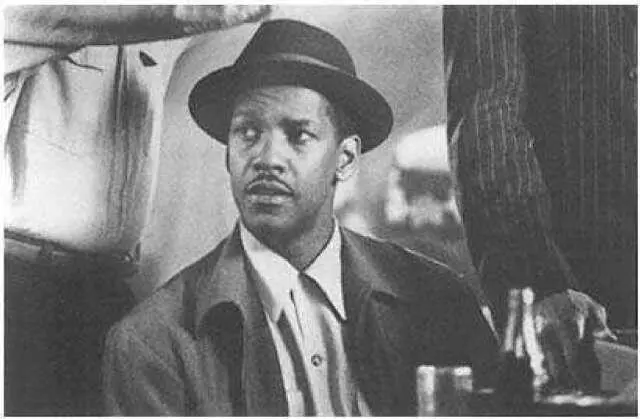

Although the film's protagonist, Easy Rawlins (Denzel Washington), is both a private eye and something of a knight errant, his motives are far more realistic than Philip Marlowe's, and his life is placed in much greater jeopardy. Marlowe's skin color and social polish enable him to move with relative ease through every level of the city, whereas Rawlins faces barriers each time he steps outside his immediate community. In the course of his investigation, he narrowly escapes being beaten or killed by college kids on Santa Monica Pier; he is sadistically roughed up by the white gangsters who hired him; and he is brutally assaulted by the Los Angeles Police Department, who give him a single day to solve a murder or die. He uses every skill at his command merely to stay alive, and in attempting to solve a mystery, he defamiliarizes the entire city. As Paul Arthur observes, in this film, "the white districts and their bases of individual and institutional domination . . . serve as the heart of darkness." 28The dance clubs and pool halls along (Central Avenue are shadowy and sometimes violent (especially when they are invaded by whites), but they seem more accommodating than Santa Monica Pier and the Ambassador Hotel. Throughout, the white world is a dangerously alien territory at the margins of "normal" life, and poor and semirural areas that were never represented by the classic studios are given an aura of peace and dignity.

Like most noir heroes, Easy Rawlins is a loner with a "dark" past, which is represented in the film by a brief flashback to his life of crime in the prewar South and by several references to the dead bodies he saw in Europe while fighting for the United States Army. Unlike his predecessors, however, Rawlins does not suffer from guilt or quasi-existential angst. He wants nothing more than a steady job, so that he can satisfy the American dream of having a home with a bit of lawn attached. Hence the normative locale of the story is not, as in Chandler, a detective's lonely, rented office in Hollywood, but a privately owned bungalow in working-class Watts, where we see children at play in the streets. "I guess maybe I just loved owning something," Rawlins tells us in his offscreen narration, as we see him driving up to his mortgaged, one-bedroom housea sunny dwelling with hardwood floors, a breakfast nook, and a pleasant front porch looking onto a patch of grass. The film's production designer, Gary Frutkoff, has skillfully selected and decorated this house, in the process giving a new twist to the theme of male domesticity in private-eye fiction: Rawlins lives in self-sufficient, Marlowe-like isolation, but he is also a housekeeper and a benign embodiment of capitalist progress, who enjoys planting rose bushes and communing with his neighbors.

When the film opens, a downturn in the postwar economy has deprived Rawlins and other African Americans of employment. (We see some of his neighbors loading up their autos and beginning a Joad-like migration back to the South.) In a bar on Central Avenue, Rawlins is approached by a white gangster (Tom Sizemore), who offers him a large sum of money to search the black side of town for a mysterious white woman named Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals). According to the gangster, the woman has a "predilection for the company of Negros; she likes jazz and pig's feet and dark meat, so to speak." But when Rawlins succeeds in finding Daphne, he discovers that she is passing for white. The sister of a black gangster from Lake Charles, Louisiana, she has become involved in an interracial love affair with one of the most influential white men in Los Angeles; moreover, she is in hiding because she has proof that a leading candidate for mayor is a pedophile. Two people who know her have already been murdered by the politician's thugs, and she and Rawlins are next in line.

Denzel Washington in Devil in a Blue Dress (1996).

(Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

The film cleverly uses the noir femme fatale to comment on the themes of racial passing and the "tragic mulatta," which were typical of American literature and film in the 1930s and 1940s. Not unlike the white Velma Valento in Farewell, My Lovely, Daphne conceals her identity by heightening the signifiers of social class and sexuality; in this case, however, a spectacular "female" body helps to draw attention from a "racial" body.

When the secret is uncovered, Rawlins must save both Daphne and himself from the increasingly powerful forces arrayed against them. Eventually, he enlists the financial help of Daphne's white lover, and his visit to this man, reminiscent of so many encounters between Marlowe and the Los Angeles plutocracy, has a truly iconoclastic quality. He also gets assistance from "Mouse" (Don Cheadle), a psychotic criminal he once knew in the South, who brings a frighteningly comic, graceful violence to every situation. The film climaxes in a bloody, nighttime shootout with the gangsters, which director Franklin stages with great brio. (In his previous film noir, One False Move [1992], he was as good as Howard Hawks or Anthony Mann at constructing lean, suspenseful action sequences; in this picture, the death of Sizemore is vaguely reminiscent of Bob Steele's elaborate death scene in The Big Sleep .) But even though Rawlins shoots the bad guys, unravels the mystery, and rescues the woman in the blue dress, the "color line" of postwar Los Angeles remains in force. Daphne cannot be reconciled with her lover and must return to Louisiana.

The color line may also have affected the film itself. Washington and Beals exchange sexual glances on the screen, but (like Washington and Julia Roberts in The Pelican Brief [1995]) they never make actual contact. In contrast, Walter Mosley's novel contains explicit, passionate love scenes between Easy and Daphne, who is described as a near blond, and who is not nearly so innocent as the character in the film. The novel also makes Mouse a far more threatening figure, and it provides several details about Easy's past in World War II, where he killed many white men. (Mosley is in fact partly.Jewish, and World War II and the Holocaust are significant elements in his fiction.) Perhaps equally important, the novel is concerned as much with incest as with miscegenation; indeed, its theme of pedophilia extends to Daphne's own father, who abused her when she was a girl.

In "crossing over" to mainstream cinema, Devil in a Blue Dress became a softer, less troubling text. In many ways, however, the film provides a strong cinematic equivalent to the novel, rewriting Chinatown in much the same way that Mosley rewrites Chandler. The Polanski film is specifically recalled in Tak Fujimoto's low-key, wide-angle photography, in Jerry Goldsmith's romantic score, and in the crucial recognition scene in which Rawlins discovers Daphne's true identity. ("Scream, so I can tell the police about your boyfriend Frank Green!" Rawlins shouts. "Frank is my brother," she replies.) But Devil in a Blue Dress depicts a more recent history, and its nostalgia has a different effect. Although it reveals the corruption beneath sleek, art-moderne Los Angeles in the same manner as any retro-styled film noir, it is designed to celebrate the resilience and tenacity of the postwar black community and to recover a lost or underrepresented culture. The beautifully orchestrated crane shots of Central Avenue show us both the neon-lit dens of iniquity and the vibrant, crowded life on the street. At the Regent Theater, we glimpse a marquee advertising Oscar Micheaux's Betrayal, and in other scenes we hear snippets of music designed to reveal that black Los Angeles in 1948 was a center not so much of jazz as of early rhythm and blues. (The film makes excellent use of "race" records never heard in classic Hollywood, including T-Bone Walker's "West Side Baby," Amos Milburn's "Chicken Shack Boogie," and Pee Wee Clayton's "Blues after Hours.") Most of all, Franklin and the other contributors give a pastoral feeling to the Watts neighborhood where Rawlins lives, conveying both its fragile economic condition and its pride of accomplishment.

Читать дальше