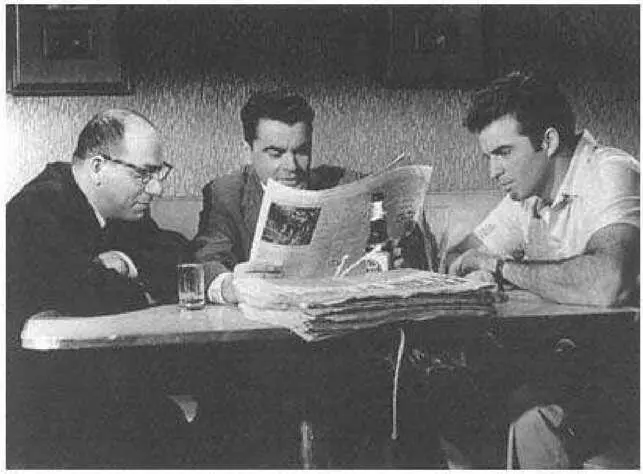

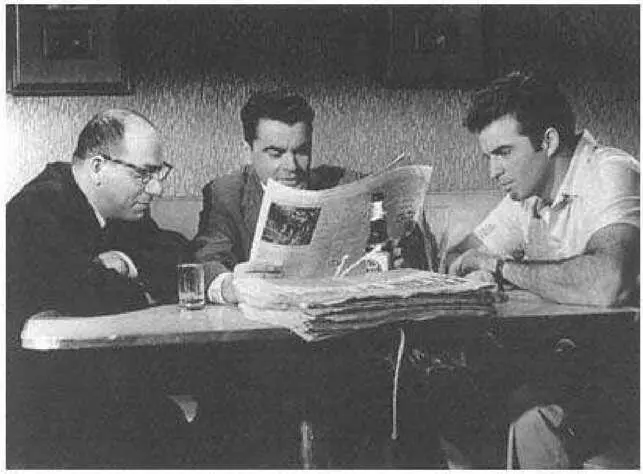

Irving Lerner's Murder by Contract (1958). (Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

Films in the tradition of Murder by Contract are still made today, but since the 1960s they have become increasingly self-reflexive. The trend may have started with Peter Bogdanovich's New Wave-inspired Targets (1968), a disturbing commentary on Vietnam-era violence, starring Boris Karloff as an aging actor who feels alienated from both contemporary America and the new Hollywood. Bogdanovich filled this inexpensive picture with references to Hawks, Fuller, and other "underground" auteurs; he inserted footage from an unreleased Roger Corman movie; he cast himself as a director; and he staged a suspenseful, Hitchcockian climax at a drive-in theater where Karloff was making a personal appearance. The result was an unusually sophisticated, densely allusive film, worthy of comparison with the best work from Europe. An even more celebrated instance of similar techniques, marking the development of an American art cinema, is Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973), which repeatedly quotes from old gangster pictures, even while it borrows camera techniques from Godard and François Truffaut. Consider also such later examples as the Coen brothers' Blood Simple (1984), which uses a Steadicam to create hyper-Wellesian tracking shots, or Scott McGehee and David Segal's Suture (1993), which takes its imagery from John Frankenheimer's Seconds (1966) and its central metaphors from poststructuralist theory. (It even has a female character named Renée Descartes.)

By the 1990s, a relatively secure place had been established in the urban theatrical market for self-consciously artful thrillers, whose budgets can sometimes be astonishingly low. Robert Rodriguez's ElMariachi (1992) was shot for only seven thousand dollars, and its well-publicized cost (which did not include distribution and advertising) helped to fuel its critical and commercial success. Meanwhile, old-fashioned pulp novelists like Woolrich, David Goodis, and Fredric Brownall of whom were discovered and canonized by the French, and all of whom are now published in designer paperbacks from Viking Presshad become favored sources for slightly upscale productions. A recent vogue for maudit author Jim Thompson began in Paris with Bernard Tavernier's Clean Slate (1981), traveled to the American independent cinema with Maggie Greenwald's Kill-Off (1989) and James Foley's After Dark, My Sweet (1990), and finally arrived in big-budget Hollywood with Stephen Frears's Grifters (1990) and Roger Donaldson's remake of The Getaway (1994). (Orson Welles anticipated these events by coscripting an adaptation of Thompson's Hell of a Woman in 1977. Unfortunately, the film was never produced.)

Meanwhile, the old Poverty Row and intermediate noirs have been remade for mediaconscious viewers. (We even have a new version of Breathless [1983].) Many of the ''original" films noirs were also remakes, but they did not acknowledge their status as latecomers, nor did they treat B movies as art. Today, because the theatrical market for assembly-line genre movies no longer exists, and because we have a fully developed noir canon, any attempt to reproduce the low-budget past inevitably involves a certain excess of style or allusiveness. Contemporary noirs therefore oscillate between elaborately designed, star-filled productions such as Heat (1996) and art movies such as Bullet-Proof Heart (1995). The best of the noir remakes, including Tamra Davis's Guncrazy (1992) and Steven Soderbergh's Underneath (a 1994 version of Criss Cross, discussed in chapter 7), tend to belong in the second category; unfortunately, however, all varieties of remade noir usually suffer from too much ambition. When Hollywood converts its old thrillers into art, it gives them more significance than they can bear; when it turns them into spectacularsas in D.O.A. ( 1988) and Cape Fear (1991)it overstates their most interesting qualities.

Nowadays, even the low-budget movies seem technically slick, and any kitsch is subject to sophisticated if cynical appreciation. The particular form of cinephilia associated with critics such as Godard, Farber, and Sarris has almost disappearedpartly because it was dependent upon a genre system that was vanishing from theaters at the very moment when its auteurs and underlying logic were being discovered. Where can we find the "faceless," unselfconscious movies of the present day and an iconoclastic critic who champions them? Certainly not in regular theaters or in alternative journalism. To see how far we have come since the days of Manny Farber, consider "Joe Bob Goes to the Drive-In," a syndicated column written by Dallas cinéaste ''Joe Bob Briggs," who enjoys thumbing his nose at liberal intellectuals and who has recently become a commentator on Ted Turner's TNT network. Joe Bob regularly lists the number of bare breasts and dead bodies in his favorite movies, and he makes frequent use of the all-purpose but relatively negative suffix Fu, meaning "an act of senseless or random violence, usually inflicted upon the viewer," as in "Disco Fu." He seems to be making fun of both the establishment and the Bible Belt yahoos, but in reality his cultural politics are quite safe. He is an ersatz good old boya carefully constructed persona who enjoys redneck camp and who writes about a "drive-in" culture that no longer exists (if it ever did). His true beat is the ever-expanding but relatively anonymous world of DTV (direct-to-video production), and his mission is to provide a consumer's guide to the soft-core, white-male pornography that fills the average video store: sadistic horror movies, violent adventure pictures, and "erotic thrillers"films that seldom play theatrically except in foreign countries and that ordinary critics barely notice.

During the mid 1990s, DTVs became a seventeen-billion-dollar-a-year industry, involving more money than all the major studios combined. Their average production budgets, however, have remained in the one-and-a-quarter- to two-million-dollar range, at a time when theatrical movies often cost somewhere between fifteen and eighty million. One reason for their low cost is that DTVs require no promotional hype; they attract customers chiefly on the basis of video-box art, much as the old pulp novels relied on cover paintings, and they build followings through word of mouth. Then, too, they are inherently cheap to make. According to Lance Robbins, vice president of Saban International Pictures, they use limited locations and only a few basic characters: "(Think a blonde, a detective, a gun and a car.)." 26

Barbara Javitz, president of Prism Pictures, which was responsible for the hugely successful and quite noirlike Night Eyes series of DTV films, explained to the Los Angeles Times that "we have been able to fill a niche that the studios weren't attending to. . . . As major features have become more costly, and as society has become more voyeuristic, we've been able to come up with more of these erotic thrillers, what used to be called B-movies." Javitz's allusion to Poverty Row is in many ways appropriate, although the typical erotic thriller also functions a bit like Playboy magazine, providing luxurious backgrounds and masturbatory fantasies for lonely men with VCRs. Such films often feature former Playboy models like Shannon Tweed or Shannon Whirry, and their plots usually involve some combination of voyeurism, striptease, lesbian sex, two-on-one sex, and mild bondage. Playboy Films, a subsidiary of Paramount, has even begun to produce its own DTVs, including two noirlike pictures of 1995: Cover Me ("a female undercover cop descends into the steamy sex underworld to crack the case of a cover girl killer") and Playback, which has no connection to Raymond Chandler's novel of the same name ("passionate partnerships and dangerous deals are on the agenda in this sexy corporate thriller").

Читать дальше